How Electronic Arts stopped being the worst company in America

After being named the worst company in America two years in a row, current and former executives, employees and partners tell us how EA redeemed itself.

The day before Consumerist.com announced the worst company in America, Larry Probst was already pissed.

That cloudy April day in 2013, Probst, interim CEO of Electronic Arts, called an emergency meeting of his senior leaders at the company's Redwood City, Calif., headquarters.

Probst knew that EA, which had grown into one of the world's largest video gaming companies since it was founded in 1982, was struggling. Its financial performance wasn't meeting expectations, its stock had fallen two-thirds over the last six years and a loud group of critics were probably about to crown the company the worst in America -- for the second year in a row.

In fact, more than 250,000 people cast their votes on the advocacy website Consumerist and crowned EA the worst company in America the year before, beating out Bank of America.

"Consumerist readers ultimately decided that the type of greed exhibited by EA, which is supposed to be making the world a more fun place, is worse than Bank of America's avarice, which some would argue is the entire point of operating a bank," wrote Consumerist's Chris Morran while announcing EA's first win in 2012.

Nearly 78 percent of votes went to EA again the next year, declaring it worse than the tardiest airlines or the reviled cable companies that take forever to service your home.

"It was a hideous thing," Probst said of finding the company so hated. In that conference room on that cloudy Monday, with the executive team surrounding him, Probst "hit the roof," as one person described it.

"The message I tried to deliver was, 'This will not happen again,'" Probst recalled in an interview a year and a half after the gathering. "'As long as I draw breath, this will not happen again.'"

Why were EA's critics so ticked off? They had a long list detailing how the company lost its way. Some of the games it released weren't considered as innovative or well made as the originals, particularly titles like Medal of Honor: Warfighter. The 16th major installment in the series was criticized for not innovating on the typical shooting game. Other players loathed EA's shift toward selling additional storylines to games for an extra fee. And its efforts to compete with a new class of games by Zynga and others, offered cheap or free on smartphones, tablets and Facebook, weren't well received.

EA seemed more like a business than a game developer, said fans turned critics. "EA doesn't even have the decency to recognize when they've published another uninspired piece of crap," one blogger at the gaming enthusiast site Destructoid wrote at the time.

Winning the worst company award served as a wake-up call for EA, helping to convince executives they needed to change the way they thought of their customers. That rethinking has paid off. Over the past year, EA's sales, which declined in the year leading up to Probst's April meeting, have swung back to growth. Profit has skyrocketed to $875 million from $8 million in 2014, and the company's stock price has soared.

All with little change in research and development investment and no dramatic layoffs.

Every company at some point faces a crisis of confidence. At EA, this challenge manifested itself in a peculiar way: customers were buying its games, but an increasing number of them also disliked the company. A lot.

So, EA set about changing its culture, from the way employees worked with one another to the way they talked to customers.

"We needed to look at systemic problems," said Patrick Söderlund, who heads up some of EA's biggest games. "We needed to understand this is how people perceive us -- right or wrong, it was as simple as that."

Big game, bigger response

EA's roots go back to some of the earliest days of the video game industry. In 1982, Trip Hawkins, a director of strategy and marketing for Apple, founded the company as a video game publisher. He called it "Amazin' Software," but ultimately wanted a name that presented games as an art form.

Electronic Arts released its first blockbuster title in 1988, John Madden Football. The game wasn't much back then -- crude blobs on a green field, with statistics like time left and yard line at the top of the screen. Even so, fans were hooked. The game and its sequels built one of the best-selling franchises of all time.

Today's Madden strives to look as realistic as possible, with characters designed after real-life players in the National Football League. Over 100 million copies of the game's more than two dozen editions have been sold in the last 27 years.

So what led EA to go from being celebrated to despised?

Some gamers point to Mass Effect 3 as a seminal moment in EA's history. Released a month before Consumerist's vote in 2012, it was the latest title in a series about space-age wars and the threats to life on Earth. Fans loved the franchise, particularly because it offered players choices that affect how the story unfolds. EA sold 890,000 copies during the game's first day on the market.

But then gamers got to the ending and no matter how they played, the tale of the game's larger-than-life hero, Commander Shepard, ended with what felt more like a hasty tie-up than a satisfying resolution to an epic three-game buildup.

Players were furious. They wrote in, complained online and signed petitions demanding EA to change the story. But the company refused to change the way the game ended.

To EA, it was a matter of artistic independence. Movies don't change their endings after being criticized, so why should a video game?

To some customers, it was arrogance.

The dispute between the company and its loyal fans couldn't have come at a worst time. EA was struggling to adapt to a quickly changing industry. Spurred by the popularity of smartphones and social-networking sites like Facebook, millions of new gamers were flocking to titles like the puzzle game Angry Birds by Finnish developer Rovio Entertainment, and the world-building game FarmVille by a then-startup in San Francisco called Zynga.

While these games didn't have the visual sophistication EA considered its competitive edge, they were addictive.

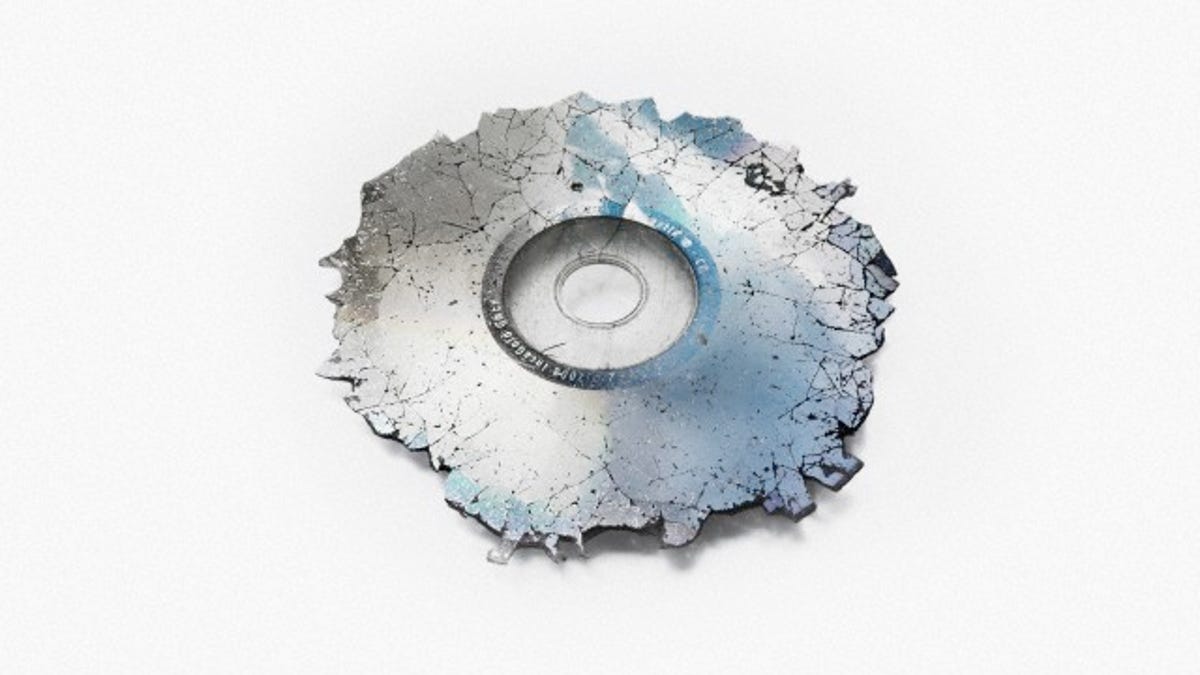

John Riccitiello, EA's CEO from 2007 to 2013, had seen much of it coming. In August 2007, he told a Manhattan ballroom filled with the company's senior leaders that EA's business of putting games on discs, shipping them in boxes to stores and selling them to customers for $60 apiece was waning and would eventually evaporate. The future was the Internet, where games were purchased and delivered online.

He pushed the company to begin making games for mobile devices, and he oversaw the acquisitions of Chillingo and Playfish in 2010 and 2009. The former had helped bring Angry Birds to prominence on Apple's iPhone, the latter was one of Zynga's biggest competitors.

At the same time, he laid off 1,500 employees over two years so he could bring in new talent accustomed to making and selling games over the Internet. That shift came at a cost, though, setting up a culture clash with employees who'd been accustomed to creating games on discs.

EA built sophisticated computer systems to begin tracking customers' behavior, from their purchasing decisions to how they played games. The amount of information was astronomical. Today, EA collects more data in 24 hours than the US Library of Congress has in its entire archives.

The flood of information changed EA, executives and employees said. The company struggled to understand all this new data about customer's behavior, and how to apply it to making games. And it didn't seem to value storytelling and bold new ideas as much, they said.

"Data helps keep everyone honest and it tells you if your game is compelling or it isn't, but it doesn't tell you what they didn't like," said Emily Greer, head of Kongregate, a gaming service owned by retailer GameStop. "It doesn't help you find the soul of a game."

Turning the Titanic

That group of executives who met with Probst in April 2013 ultimately became what he called a rehabilitation group. Their job was to fix customers' complaints.

"Very early on, we developed a list of policies," Probst said. "We systematically went down the list -- what can we do differently?"

Among them, EA created a "Great Game Guarantee," offering customers a full refund, for any reason, of a game purchased through its online store within 24 hours of first playing, or in the first seven days of purchase.

The company also did away with a draconian feature it built to fight piracy and reselling of used games, which required customers to type in a code on their computer or game console.

See also: Five ways Electronic Arts got back into the game

Next, EA worked on fixing its relationship with customers. Gamers are not like most normal people; they're committed, passionate, enthusiastic consumers who go all in when a new game they want is released. Some sit in front of their screen, mashing on buttons for hours -- or days -- until they finish the latest title. The company needed someone at the helm who understood them.

In September 2013, Andrew Wilson was named EA's new CEO after Riccitiello left abruptly. Then 39 years old, Wilson had rapidly risen from being a developer in the company's Australian offices to head of its sports games, including Madden football and FIFA soccer. He'd also overseen the company's "Ultimate Team" services, a form of fantasy sports that became a bedrock of the company's games and profits.

Wilson is boundless energy in a suit. He speaks with a deep, enthusiastic Australian accent, looks you straight in the eye and cracks self-effacing jokes.

He lives the kind of life that breeds excitement. He's an avid surfer who practices Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and he's loved fast cars since he was a kid. A blogger in the UK once called him "a fist-bump, in human form."

He also understood data wasn't the only endgame. "Data tells us more about players than we ever did before," he said during an interview in a conference room with the words "Be Human First" written on the glass. EA's future, he added, is in blending the data and creative sides of a company.

"The challenge with data is you never seek to do anything profound or inspired," he said. "You just do what the data tells you."

But first he needed to help leaders at the company understand why EA was struggling.

Five months after taking over, on February 12, 2014, Wilson gathered 146 of the company's top leaders at EA's headquarters. Together with Gabrielle Toledano, EA's chief talent officer, Wilson hatched a plan to help them understand why so many customers were unhappy.

The group was led to the basketball court, which had been temporarily remade into a conference space with stations of computers and telephone lines. For hours, executives went through the steps of installing, troubleshooting and playing the company's games. They also listened in on customer service calls so they could hear firsthand players' frustrations.

"We weren't thinking about everything we were doing in the context of the player experience," said Wilson.

Söderlund was in that room. A former volleyball player who rarely smiles for a photograph, he's worked at EA since 2006, when it bought his game development studio. He now headed the division responsible for some of EA's biggest games, including the Need for Speed racing series, Dragon Age adventure titles and Battlefield war simulation games.

He knew customers were unhappy, but when he sat down and listened to a customer lash out at a service agent, it struck him. Some executives had been dismissive of customer complaints and even looked at the worst company votes as a fluke. They couldn't be any more.

Over the course of that two-day meeting, Wilson discussed the importance of taking risks with new franchises and creative games. He brought in players to talk to the executives, including one from the Navy who talked about how every year when Madden was released the ship's commander demanded that the first person who received a copy had to play with him. "Madden is our escape," Wilson remembered the man saying.

A mantra Wilson wanted executives to rally behind was one of its codes of conduct, "Think Players First." That meant making decisions in the best interest of customers, rather than merely for the company. It was about doing right by customers the first time around, be that by delaying a game to make it better, or offering freebies as an apology for screwing up.

EA soon put that ideal to the test.

Risking millions

Söderlund went back to his office in Sweden and faced a new challenge. There was an unexpected hiccup in the development of a highly anticipated new title, a futuristic war game called Titanfall.

Söderlund had been trying out the game on the newest Xbox, the Xbox One, released in November 2013, and it was going great. But an engineer whose job was to ensure the game's quality said it wasn't running well on the older Xbox 360, originally released in 2005.

So he tried it and immediately knew it wasn't acceptable. The animations weren't running fast enough, and when he shot a virtual bullet, it didn't seem to hit at the right time. "We couldn't ship this," Söderlund said. So he asked EA's executive team to push back the launch by a few weeks.

Eighteen days might not sound like much, but delaying a big-budget game is no small decision. It isn't just a matter of keeping boxes off store shelves and sending an apology email to eager customers. Companies commit to advertising blitzes on TV, radio and the Internet. Shelf space and shipping partnerships are set months in advance. Changing things last minute can cost millions of dollars.

Still, Wilson and the executive team approved the delay almost immediately. That was a surprise to Söderlund, who said a delay likely wouldn't have happened before Wilson's retreat -- a sentiment other EA executives echoed. "I've never had a project have a ship date move," said Steve Papoutsis, who left his job as general manager at EA's Visceral Games earlier this year.

In June 2014, EA began the next phase of its makeover by extending an olive branch to players, offering them to play pre-release versions of its games.

During a presentation at the Electronic Entertainment Expo, one of the year's largest video game conventions, EA released a public test of its next big game, Battlefield Hardline. Söderlund's team had spent two years working on the game. Giving access to players so early was unusual, but EA decided it needed to be more open and communicative with players. It wanted to offer them insight into how it builds games, and allow them to influence the way they're made. Giving players early access was part of that.

More than 1.7 million customers signed up to play for free over 12 days of testing. When it was over, EA made the decision to delay that game too, from its October planned release to March 2015. Some of the customer responses to the game were factored in, including making it more challenging in some areas and changing the way various guns or gadgets worked. When EA held another public test in February, 7 million players joined in.

The next step

Talk to any EA executive and they'll say plenty more work needs to be done.

The company has notched some important wins, including accolades for its latest Dragon Age adventure game released last year, and it's regained enthusiasm of investors. But it faces large and growing expectations for its upcoming slate of titles, including its Star Wars tie-in game, Battlefront, which is being developed by the same studio behind Battlefield. EA is expected to discuss more details about that game, and others, during its presentation at the upcoming E3 video game expo this month.

Analysts say EA needs to begin fielding entirely new games, with fresh storylines and different characters for customers to obsess over. "They have been doing some interesting things and I am excited for upcoming titles," said Zachary Reese, a senior editor at UFF Network, a group of video game fan sites. "I hope they start to take more risks."

In the next year, Wilson said he will appease critics by laying out his vision for the future, which involves making games available on every device imaginable, from a smartwatch to a smart TV. EA has already begun exploring offering games through partnerships with cable companies, for example. And it's begun focusing development on creating games players want to play for months or years on end.

Most importantly, customers seem to like EA again -- at least for now. In 2014, the company was knocked out of competition for the worst company in America during the first round of voting. The winner that year: Comcast.