Two-legged dinosaurs swung their tails to run, just like humans swing their arms

That tail's not just for looks; it helped certain dinosaurs strut with style.

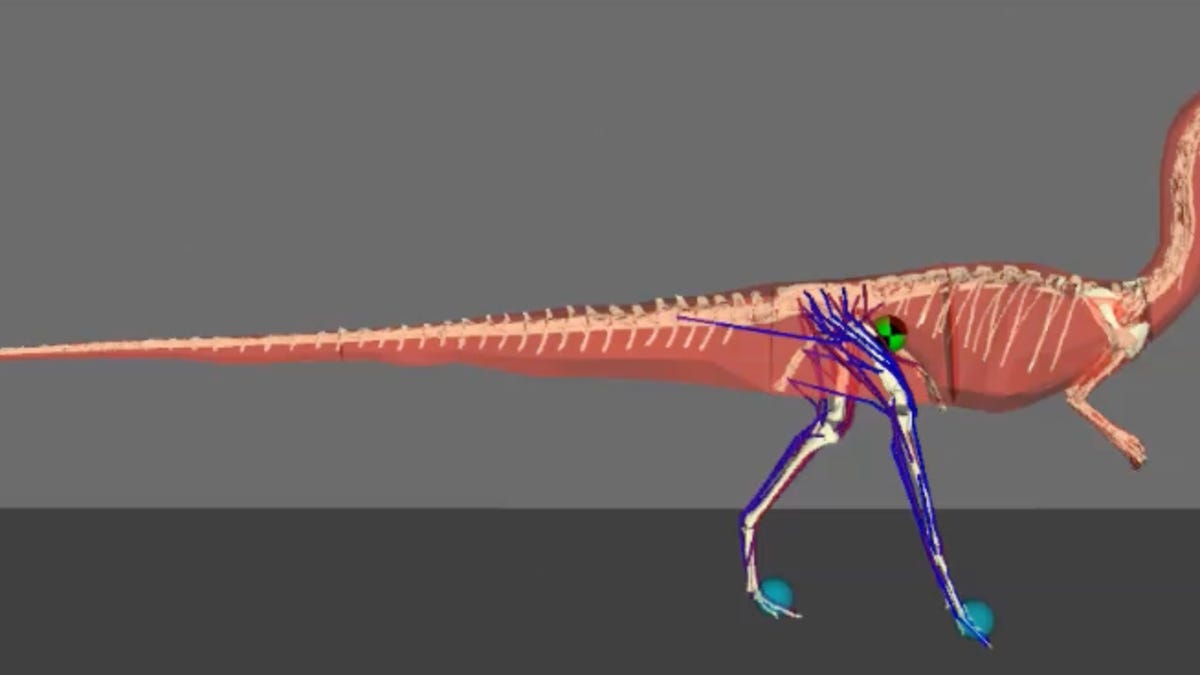

This still from a video simulation done for the new study shows the impressive tail of the Coelophysis bauri. Its movements helped the dinosaur move quickly and easily.

The dinosaurs have been gone for millions of years, but we're still learning more about them. According to a new study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, certain small-armed, two-legged dinosaurs may have swung their tails from side to side to help them move, kind of like humans swing their arms when they walk.

Experts frequently assume that non-flying dinosaurs used their tails in numerous ways, but this study is the first to examine the tail's role in helping them move.

"As a key aspect of behavior in many animals, understanding locomotion is integral to deciphering the biology of extant and extinct species," the study notes.

Researchers created a 3D computer simulation of a dinosaur called Coelophysis bauri, which lived 200 million years ago, using the model of the elegant crested tinamou, a South American bird that is similar to the dinosaur.

By playing with the simulation, they determined which body parts did what while the dinosaur moved, turning some off and on to test theories. And they found something surprising.

"We assumed that [the tail] would just be there hanging," lead study author Peter Bishop told Live Science. But it turned out the tail was doing much more than hanging.

When the tail was taken out of the simulation, it was much more difficult for the dinosaur to stay balanced while running. That helps researchers form a more complete picture of how exactly these long-extinct creatures moved. That may not seem like vital information to know, but it's opened a door into how scientists can continue to get a fuller picture of dinosaur anatomy and movement.

"We are now primed to explore locomotion and other behaviors in a whole host of other extinct critters, and not just dinosaurs," Bishop told Gizmodo. "Pretty much anything is fair game. This is the great power of the simulations -- that they allow us to explore anatomies that have no modern equivalent, and thereby test questions that are otherwise impossible to answer."

The new information probably isn't limited to just Coelophysis bauri.

"We infer this mechanism to have existed in many other bipedal non-avian dinosaurs as well, and our methodology provides new avenues for exploring the functional diversity of dinosaur tails in the future," the report says.