It's 50 Years Since Humans Stepped on the Moon: Why We Gave Up and Why We're Returning

The most recent boot-print on the moon was left Dec. 14, 1972. A half-century later, we're preparing for a new visit.

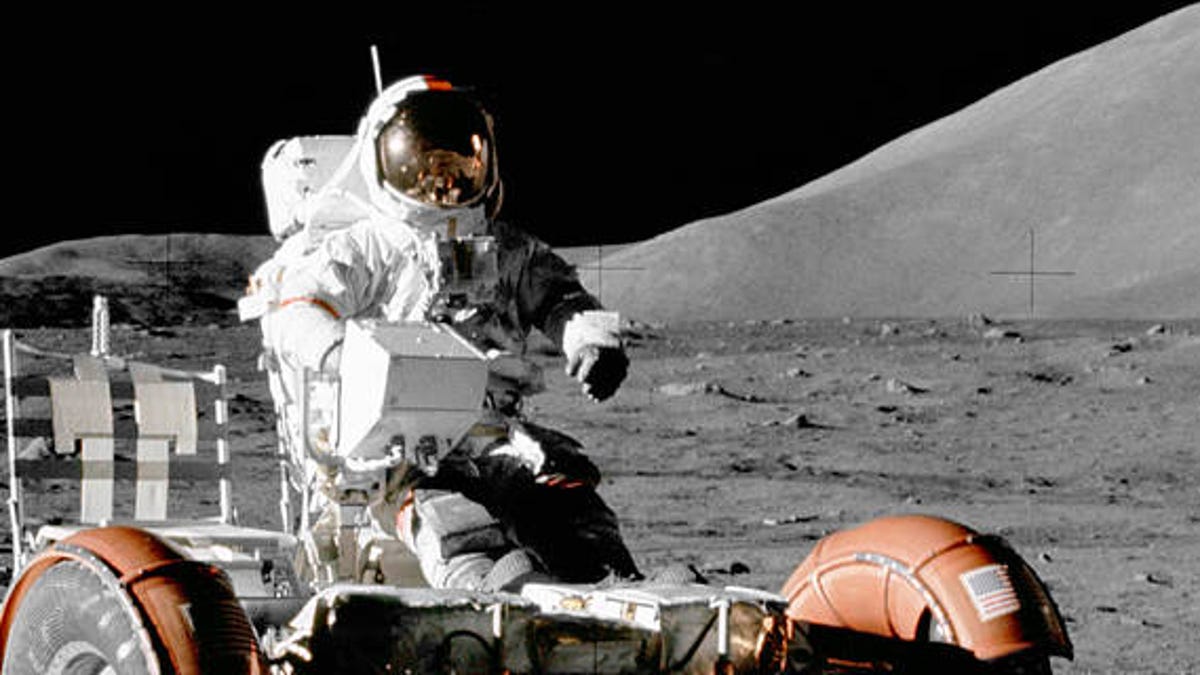

Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan in the Lunar Roving Vehicle on the moon in 1972.

The Apollo 11 astronauts famously laid down the first human boot prints on the surface of the moon in July of 1969. It's a little less well known that the last prints from human activity on our lone natural satellite were imprinted just three and a half years later.

Astronauts Eugene A. Cernan, Ronald E. Evans and Harrison H. "Jack" Schmitt conducted a 12-day mission to the Taurus-Littrow region of the moon, during which time they collected more moon rocks and other geological samples than any other Apollo mission. On the way to their destination, they also captured the iconic "blue marble" image of Earth, which gave humanity one of the best views of our home up to that point in history.

As the Apollo 17 crew left the moon on Dec. 14, 1972, Cernan commemorated the moment by telling Mission Control: "We leave as we came, and, God willing, we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind."

Cernan lived until 2017 but didn't live to see the return he spoke of on that historic trip.

In total, only 12 people have set foot on the moon in the multibillion-year history of the rock, and they all visited over a single 38-month period.

Why we moved on from the moon

The creation of NASA has its roots in Cold War anxieties and the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Soviets were out of the gate quick with the successful launch of the first satellite, Sputnik, and the first person in space, Yuri Gargarin. Apollo 17 came a full decade after President John F. Kennedy's bold 1962 promise to land men on the moon before the decade was out. NASA not only met its self-imposed deadline, it went back a handful of times too.

But a lot of other things were happening on Earth at the time. An unpopular war raged in Southeast Asia, and civil unrest in the streets of American cities led evening newscasts, to say nothing of the multiple environmental crises that were becoming mainstream concerns. The US government had sunk a massive amount of taxpayer money into Apollo, and the program's popularity was waning just a few months after Neil Armstrong's "giant leap for mankind" captivated the world.

Taller than the Statue of Liberty, the Saturn V Heavy Lift Vehicle rocket was a key piece of NASA history. The space agency built it to help get astronauts to the moon. "The rocket generated 34.5 million newtons (7.6 million pounds) of thrust at launch, creating more power than 85 Hoover Dams," says NASA. Saturn V first flew in 1967 for the Apollo 4 mission. The last Saturn V took off in 1973 and ferried the Skylab space station into Earth orbit. This image shows the Skylab launch.

"Running parallel with the social revolution of the 1960s, Apollo experienced many incredible triumphs as well as tremendous setbacks (cancellation of several final missions) and tragedies (Apollo 1)," writes NASA chief historian Brian Odom in a recent blog post.

In January of 1970, all Apollo missions beyond Apollo 17 were canceled due to cuts in federal funding. The threat of Soviets in space was no longer top of mind for most Americans, who were facing a recession and rising inflation, a harbinger of a tough economic decade to come in the 1970s.

After Apollo, NASA's focus shifted to orbit, first with the Skylab space station and hen with a space shuttle program that ran for three decades until 2011.

So this Wednesday marks a full half-century since the most recent moment there was any human presence, not just on the moon, but anywhere beyond low Earth orbit.

Space shuttle Atlantis touched down after its final mission in July 2011. This image comes from a sequence of landing shots and shows the shuttle's drag chute, used to slow down the spacecraft. This landing also marked the end of NASA's iconic space shuttle program.

Making a home in space

To be fair, we've kept our astronauts quite busy in orbit, where the International Space Station remains one of history's most notable examples of international cooperation. Today, with European and American relations with Russia at their lowest point since at least 1991, Russian cosmonauts and astronauts continue to live and work together productively, even when leadership on the surface starts a little saber-rattling.

Priorities began to shift a bit once again as the shuttle was winding down in the late 2000s. A new push to return to the moon and continue on to Mars began to gain momentum, both inside and outside NASA. The US Congress committed to invest billions to build a huge new rocket, while Elon Musk and SpaceX were building toward similar ambitions.

Unrealized futuristic predictions from the mid-20th century imagining how we would live on sci-fi space stations and explore Mars returned to the zeitgeist.

Almost exactly a half century after Apollo 17, NASA's uncrewed Artemis I mission earlier this month traveled further beyond the moon than any human-rated spacecraft ever, and it captured a new iconic image for a new generation of exploration, showing both the moon and Earth from a new perspective.

Orion, the moon and Earth appear together in a photo.

NASA and SpaceX have committed to joining forces to return a new generation of astronauts to the surface of the moon before the decade is out. It's a familiar promise, which worked out last time.

It's probably no coincidence that some of the circumstances from the original space race are beginning to replay today, too, with a new geopolitical rival, China, increasingly pushing forward an ambitious space exploration agenda. China's space program is currently launching dozens of rockets each year and operating its own space station, lunar and Mars rovers. The Chinese space agency has also stated its goal of building a crewed station on the surface of the moon, which is also a primary goal of NASA's Artemis program.

NASA historian Odom points out that much of the lasting legacy of the Apollo program is still present on Earth.

"The federal investment in aerospace infrastructure across the southern United States transformed the economics of much of the region. Critical investments in university engineering and science programs created foundations that continue to pay off with technological and scientific breakthroughs."

Odom is optimistic that Artemis will yield a new round of scientific discoveries and engineering innovations.

"Hopefully the lessons of Apollo will prove a helpful framework for discovery both on the moon and back home. If we are paying attention, I am sure they will."