Astronomers Unexpectedly Capture 'Great Dimming' of Supergiant Star Betelgeuse

A Japanese weather satellite saw the mysterious dimming unfold in 2019 and 2020.

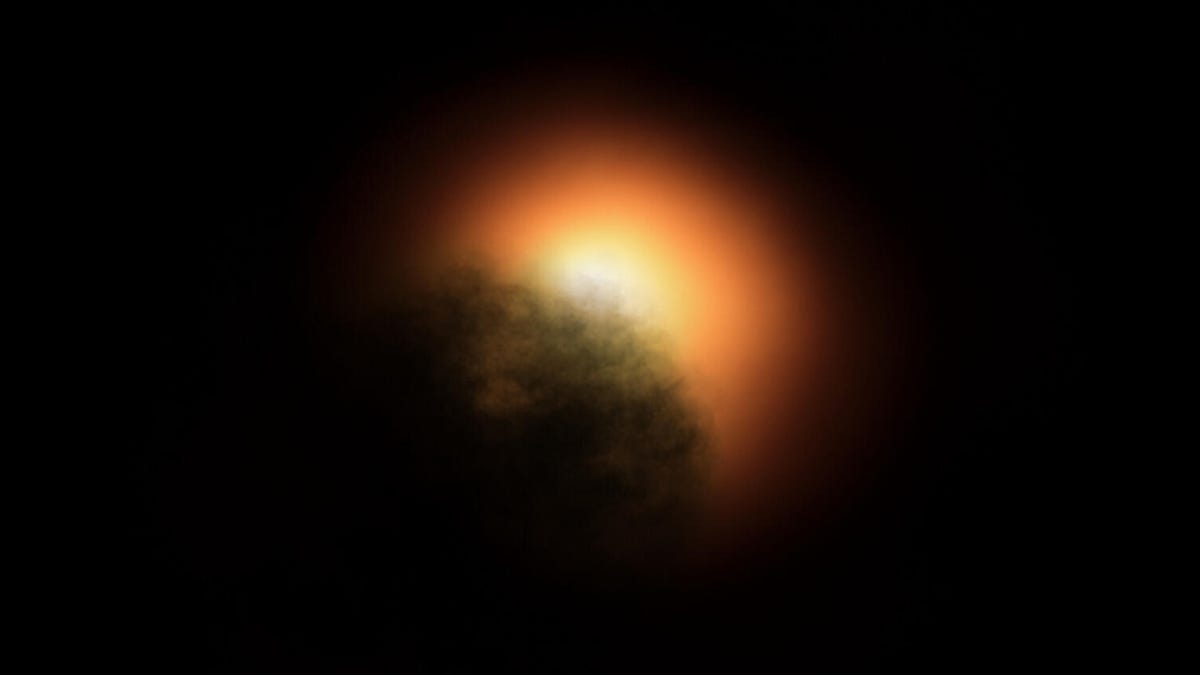

This artist's impression show the Great Dimming of Betelgeuse, which saw the fiery star dramatically decrease in brightness at the end of 2019.

Just a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic really kicked off in early 2020, the world was fixated on a distant supergiant star, 700 light-years away known as Betelgeuse. The monstrous furnace suddenly dimmed, becoming 10 times darker than usual. Some suggested it heralded an explosion, but rumors of the star's demise were greatly exaggerated. It brightened up just a few months later.

Several teams took to trying to explain what had caused this "Great Dimming" with one team analyzing hundreds of images of the star to reveal stardust was likely obscuring our view from Earth. In June 2021, they showed that Betelgeuse had likely belched out gas, which then cooled and condensed and darkened the star. Another group suggested the star was also cooling just a little and this variability also may have resulted in a decrease in brightness. At the very least, it contributed to the formation of the dust cloud.

Mystery solved? Perhaps, but there's one more unexpected find from the Great Dimming.

In a new study, published in the journal Nature on Monday, a trio of astronomers detail their own surprising discovery: They were able to spot Betelgeuse lurking in the background of images taken by a Japanese weather satellite, Himawari-8. The serendipitous find helps confirm some of the earlier work uncovering the origins of the Great Dimming and points to a new way to explore our cosmic neighborhood we haven't explored.

Himawari-8 is, as the name suggests, the eighth version of the Himawari satellite operated by Japan's Meteorological Agency. It operates in geostationary orbit, at a distance of 22,236 miles above the equator. This is more than 90 times further away than the International Space Station.

From that position, the satellite snaps optical and infrared images of the whole Earth once every 10 minutes, predominantly to help forecast the weather across Asia and the Western Pacific. For instance, it snapped a ton of images of the Tongan volcano eruption that occurred on Jan. 15. However, looking through images stretching back to 2017, the trio of Japanese researchers went looking for a pinprick of light that would be Betelgeuse, lurking in space behind our brilliant blue and green marble. They found it.

Studying that pinprick of light, the researchers came to the same conclusion as their predecessors: Betelgeuse dimmed because of both dust and some natural variability in its light. That's not all that exciting, but it's good confirmation we're all on the right track, and it's exactly what the process of science is all about.

What is intriguing is the fact a weather satellite was able to provide this data in the first place.

It could be a big deal for astronomers. Building and launching new space telescopes isn't a cheap or easy endeavor and you have to book yourself a rocket. But... there are already satellites orbiting the Earth that might be able to do a similar job.

"Himawari is like a free space telescope!" said Simon Campbell, an astronomer at Monash University in Australia.

Weather satellites like Himawari-8, for instance, are constantly imaging the Earth and the space around our planet, providing mountains of data to sift through. This is important because astronomers usually have to make a case for time on telescopes, carving out blocks for their projects that allow them to control where the telescope is focused.

For instance, when Betelgeuse mysteriously dimmed, some of the most powerful telescopes on the ground were already booked to look elsewhere. One, the Very Large Telescope in Chile, gave a team the chance to use its telescope for observations, knocking other projects back. But these cases aren't always ticked off.

So, Campbell noted, there's a neat story here about observing space. You could look at Earth imaging satellites in orbit and repurpose them to study background stars. Another advantage of this is they can observe over 24 hours and may be able to see in additional wavelengths of light like infrared, which is blocked by Earth's atmosphere.

Ultimately, the next time a star threatens to go supernova on us, we might already be watching.