First 'true' millipede with over 1,000 legs discovered deep below Earth's surface

Emerging from a drill hole in Western Australia, a new record holder for leggiest animal on the planet.

Around the world, more than 7,000 species of millipede crawl across forest floors and garden beds, pairs of legs pumping as they move through soil in search of food. The limbs can number in the dozens to the hundreds, and while the term "millipede" translates to "a thousand feet," the record number of millipede movers has stood at around 750 legs since the description of a Californian species back in 2006.

"Millipede" has been a misnomer. A thousand feet? A myth. Until today.

"All of the introductory textbooks will have to be rewritten because there is a true millipede now," says Dennis Black, a millipede expert and adjunct research fellow at LaTrobe University in Australia.

The "true" millipede has been dubbed Eumillipes persephone. The new species was discovered in a borehole, drilled as part of a Western Australian mining operation, almost 200 feet (60 meters) below the Earth's surface. It's the first millipede to live up to its multi-legged moniker with a staggering 1,306 legs.

"That's just an amazing number," says Paul Marek, an entomologist at Virginia Tech and lead author of a paper documenting the find, published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports. "I'm still in disbelief."

Named for Persephone, the Greek goddess of the underworld, the spindly, brown crawler is just over 3.7 inches long and about as thin as a USB cable. The millipede also lives much deeper in the soil than any previously known species, and the story of its discovery makes for a tale of great luck and incredible irony.

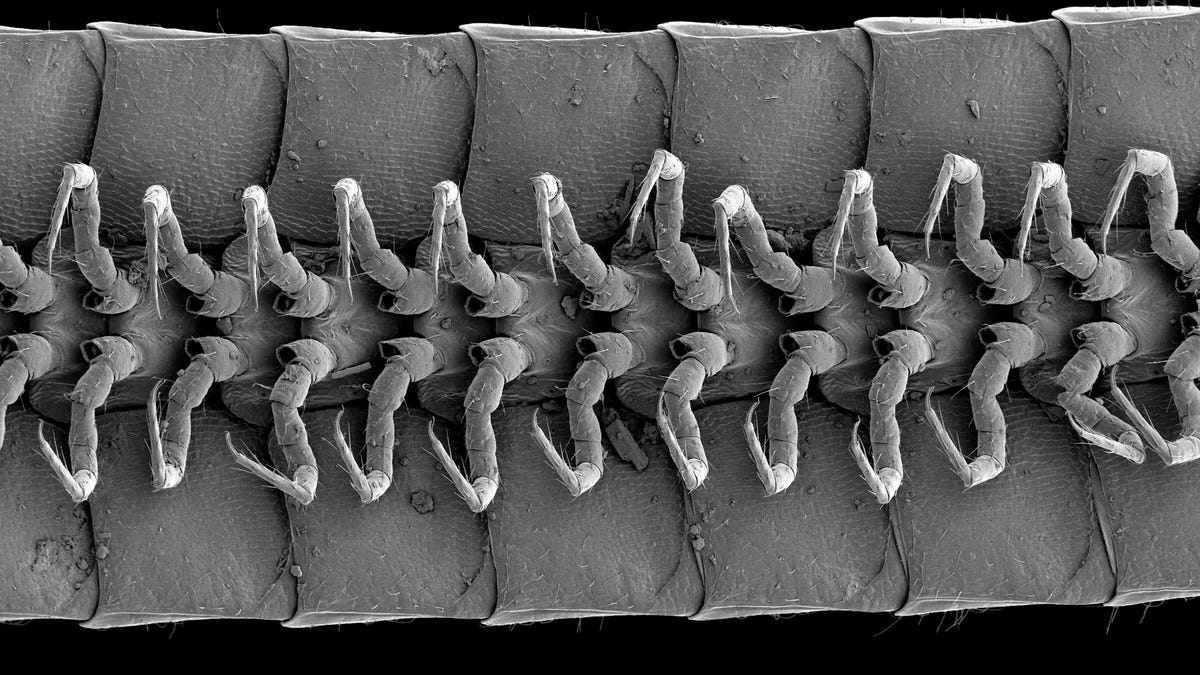

If you've got time, maybe you can count up all the legs -- you'll find 1,306.

Portal to the underworld

The first person to set eyes on the Persephone millipede was Bruno Buzatto, principal biologist at Bennelongia Environmental Consultants in Western Australia. The group specializes in subterranean surveys of animal life and is often contracted by mining companies looking to perform environmental assessments as they search for resources. The mining companies drill the holes that, Buzatto says, are like "portals" into the subterranean world.

To assess what life lurks in the underworld beneath our feet, Buzatto sends "traps" through the portals. He takes a plastic tube with a few holes in the side and fills it with leaf litter. He then drops it down one of the drill holes and leaves it there. Life in the soil is attracted to the litter, hoping to fill its stomach. When Buzatto pulls the trap out a month or two later, it's often teeming with life.

Buzatto says these traps routinely catch new creatures, some of which have never been seen before. "About 80 to 90% of what we pull up is undescribed species," he says. So it was no surprise to him when, in August 2020, he laid eyes on an unusual animal he'd never seen before. In a haul plucked from a hole in the Eastern Goldfields Province of Western Australia, Buzatto found an extremely long millipede. "I realized it was a very special animal," he says.

An electron microscopy image of Eumillipes persephone's many legs.

A few years earlier, Buzatto had been flicking through a research paper about Illacme plenipes, a Californian species of millipede with the record for most number of legs. The lead author of that study was Paul Marek, an entomologist at Virginia Tech. Buzatto shot him an email, attaching a picture of his find.

"I did a quick count and it had 818 legs," Marek says. "I was pretty pumped about that."

To make it official, Marek needed to see the specimens, place them under a powerful microscope and analyze their DNA. Buzatto, in collaboration with the Western Australian Museum, shipped specimens to Marek's lab in the US. In total, the team was able to find and analyze five millipedes, with one female taking out the legs record (1,306) and a male falling just short of the mythic 1,000-leg mark at 998.

Why so many legs?

The Persephone millipede lives in a world with no light and, likely, limited food. Evolution has built it for this world with unique characteristics – similar to, but distinct from, Illacma plenipes.

When Marek was able to look at the Persephone under the microscope, he noticed many similarities to the Illacme plenipes, a millipede that lives halfway across the world, separated by the Pacific Ocean. However, it also had some bizarre features. "It was nothing like other members of the family," Marek says.

For one, it had no eyes, which is unique in this order of animals. Two, it was unpigmented.

Both changes make sense. Living in the underworld, eyes aren't all that important. You don't need to detect changes in the light. Instead, the Persephone has huge antennae. Pigmentation loss occurs in a wide variety of animals that live in places without light, such as caves, but the evolutionary pressures underlying pigmentation loss are still being fully elucidated.

All of the characteristics helped Marek and the team place the species in the order Polyzoniida, distant relatives of the previous leggiest record holder, and suggested the Persephone and Illacma plenipes are an example of convergent evolution – where two distantly related species evolve similar physiological traits to adapt to their niches.

But why does a creature need so many legs?

The answer isn't all that surprising. Legs are for locomotion. They allow you to move around the world. The researchers haven't seen live specimens moving around in their home underworld, but they can draw on insights from similar species in nature. Based on earlier studies, Marek and the team suggest the super-elongation and short legs help to burrow through the underworld, providing additional propulsive force as it moves in a telescoping motion.

"The combination of these characteristics really speaks to the importance of being able to traverse deep underground, probably as a result of a limited set of nutrients in the place that it lives," Marek said.

The head of the Persephone millipede is ... a little strange.

Minefield

There is a great irony to the discovery, one that several of the authors have wrestled with.

Collecting and describing new species from deep within the soil hasn't been done to a great extent in Western Australia. There could be dozens of species living underneath our feet that we have never seen before. Before August 2020, no one had ever seen the Persephone millipede. No one knew it existed. And it would have remained that way, if not for Buzatto's drill hole trap.

"I don't think we would have ever known about this had it not been for the mineral exploration that's occurring," says Dennis Black, the millipede expert from LaTrobe and a co-author on the study. Buzatto notes the mining company, in this instance, paid for the surveys.

At the same time, the main threat to the survival of the species, at least as far as we know right now, would be those same mining operations. If a rich resource was discovered in the same mining exploration what would win out? The millipede? Fortunately for the Persephone, Buzatto notes the area it was discovered in isn't one in which the mining company is looking to target.

Mining is a significant contributor to the Australian economy, especially in Western Australia

But it raises interesting questions about how to protect species like the Persephone we don't even know about, so-called "cryptic" organisms contributing to ecosystems we know nothing about. These ecosystems, Persephone shows, are yielding incredible discoveries and preventing further loss of biodiversity. To prevent an anonymous extinction, scientists need to know what's out there, including deep beneath the surface of the Western Australian desert.

"There couldn be a heck of a lot living over that vast area," Black says. "We simply don't have a clue."

If we did, there's a chance the Persephone too will be dethroned. Marek says there's "some correlation" between the depth at which these creatures are found and the number of legs they have. Exploring even deeper below the surface might mean running into another god of the underworld, leggier than we'd ever imagined.

"It's possible there are longer ones down there," Black says. "What I want to do is win the lotto, buy some drilling equipment and spend my retirement drilling holes."