Chinese CRISPR-modified babies could face shorter life expectancy

Chinese scientists used gene modification to make twins Lulu and Nana immune to HIV.

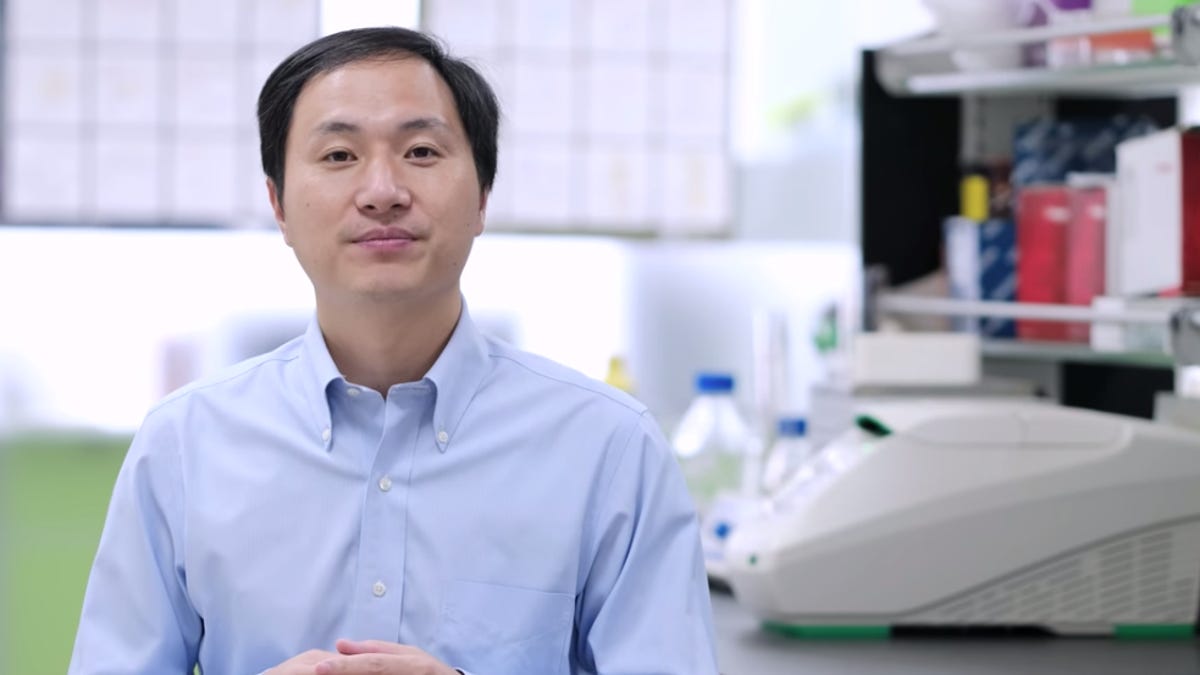

Jiankui He, a researcher based in Shenzhen's Southern University of Science and Technology.

Last November China introduced the world to Lulu and Nana, the first genetically-modified humans to be born. Lulu and Nana have modified genes that immunize them to HIV. However, a genome study from University of California, Berkeley has found there may be a cost.

A team from Shenzen's Southern University of Science and Technology, led by researcher Jiankui He, last year used emerging gene-modifying tool CRISPR to disable the CCR5 gene which, the team theorized, would lead to human immunodeficiency virus immunity.

However, UC Berkeley's study of 400,000 death and DNA records from the UK Biobank found that people with inactive CCR5 genes had a lower life expectancy than those with functioning CCR5 genes. UC Berkeley estimated a "21% increase in mortality in later life," and a "significantly higher death rate" between ages 41 and 78 for the former group.

A previous study found that while disabling the CCR5 genes may lower susceptibility to HIV, it heightens susceptibility to influenza up to four times.

"[CCR5] is a functional protein that we know has an effect in the organism, and it is well-conserved among many different species, so it is likely that a mutation that destroys the protein is, on average, not good for you," said senior author of the study, Rasmus Nielsen. "Otherwise, evolutionary mechanisms would have destroyed that protein a long time ago."

CRISPR is a gene modification tool developed in 2012 that promises to reshape the field of gene-editing forever. Often described as "a pair of molecular scissors," CRISPR is widely considered the most precise, cost-effective and quickest way to edit genes. Its potential applications are far-reaching, affecting conservation, agriculture, drug development and how we might fight genetic diseases. It could even alter the entire gene pool of a species.

He, in a video uploaded to his lab's YouTube channel last November, detailed the monumental breakthrough in gene editing, claiming the twin girls "came into this world as healthy as any other babies" and that the gene editing had worked safely -- only editing the CCR5 gene. The research team has, according to the Associated Press, genetically altered the embryos of seven couples, with just the one resulting in pregnancy so far.

Chinese scientists have been denounced for their work in human genome editing before when, in 2015, researchers in Guangzhou reported they had (mostly) successfully edited embryos. In 2016, the UK gave the go ahead to use CRISPR and edit donated human embryos in an effort to better understand developmental processes. Japan did the same in October this year. But there still remains ethical concerns over the use of the technology and some nations ban the technology completely.

"Beyond the many ethical issues involved with the CRISPR babies, the fact is that, right now, with current knowledge, it is still very dangerous to try to introduce mutations without knowing the full effect of what those mutations do," said Nielsen. "In this case, it is probably not a mutation that most people would want to have. You are actually, on average, worse off having it."