Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET Intel Core i7 3770K review: Intel Core i7 3770K

If you need to update today, then there's no doubt that Intel's third-generation Core products are at the top of the pile. If you're a Sandy Bridge owner, though, there's not much here that will tempt you over.

Watching desktop CPU evolution over the last few years has been a lesson in limitations. When pure clock speed proved to be an insurmountable barrier, multi core became the solution. It didn't take too long to get to quad core, and, when it became clear that we were never going to have multithread-optimised software everywhere, architecture overhauls came along, trying to squeeze out the best instructions per clock (IPC) that they could. While there are server and enthusiast chips with more cores, the consumer market has remained at quad, and will do so well into Intel's next CPU revision, Haswell. To go further at this point in time simply doesn't benefit the mainstay of consumers.

The Good

The Bad

The Bottom Line

And so, the game has become one of architecture refinement, which Intel's tick-tock release schedule suits particularly well. Once upon a time, a new architecture meant a new manufacturing process as well, a daunting feat to manage, and one that meant longer release times between chips. As yields improved, clock speeds of a particular architecture would slowly go up.

Not so anymore. Like the software world, these days it's about more rapid iteration, with less architectural changes between revisions. For Intel, this means iterating and optimising on previous architecture for the first year — tock — then revising by shrinking the die process for better thermal management and potential extra clock headroom the next — tick.

The tick serves an extra purpose: it allows Intel to get used to a particular manufacturing process before applying a new architecture to it, nicely insulating the company against yield issues.

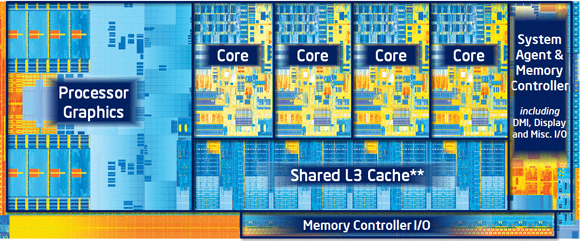

Intel's referring to Ivy Bridge as a "tick plus", thanks to its expanded graphics core, with the company claiming that just like Sandy Bridge, we're getting a doubling in performance. Just look at Ivy's die, and see how much space the graphics core now occupies.

Ivy Bridge's die, a stark reminder that progress is now focused on GPU, rather than CPU.

(Credit: Intel)

Unlike last time, though, don't expect any significant uptick in CPU performance. The reasons are twofold: firstly, this is the first outing of Intel's Tri-Gate transistors, and so, while Intel believes that it will supply plenty of head room for years to come, here it's playing it safe.

Intel's tri-gate, or 3D transistors, should give it a lot more control over clock speed and thermal output in the future.

(Credit: Intel)

Secondly, while clock speed isn't everything, and this has been proven time and again, it's just a little portentous that the i7 3770K is launched at the same clock speeds as the previous king of the hill, the 2700K. There is, of course, a reason for this.

It's not about the desktop any more

If you view Intel CPU strategy as a huge ship, Ivy Bridge, now called third-generation Core, is the point where the ship has just finished its rotation, and is preparing to go straight ahead to its new destination.

As the years have passed, we've seen the game of increasing outright performance take a back seat to another concept — performance per Watt. Rather than outright performance, there's been greater interest in how well things can perform within a certain thermal design power (TDP). AMD, Nvidia, Intel; all have changed direction to pursue this goal.

There's an obvious motivation to this: the mobile space. While currently dominated by the likes of ARM, everyone wants to play for that huge cash pile, and Intel is learning as quickly as it can to get there. While the company is still some distance from its goal, along the way, laptop users will reap the benefits of this progress.

It also means that — depressingly for enthusiasts — the desktop CPU is no longer Intel's primary focus. It also doesn't help that AMD is no longer competing in the high-performance space.

While we have no doubt that Haswell will push things along once again, unless you're in the professional segment (video editors, CAD/CAM/3D, scientists, people who like calculating Pi quicker than other people while subjecting the chip to completely unsustainable temperatures), we suspect that even the next architecture won't do a lot for your desktop computing experience. For now, depressingly, we've reached the point of "fast enough".

Gamers, whose market has typically pushed the desktop CPU along, long ago realised that a new graphics card will do significantly more for them than a new CPU. Heck, when gamers opt for mid-tier CPU instead of high end, you know your business model has to change.

Intel knows this, too, so it's no surprise that while we'll be seeing "mainstream" Ivy chips released over the next few months, the performance "halo" chip is being held back until the end of the year for the professional market. In the glory days of desktop computing, this would be unheard of; Extreme Editions and the like would always come first, heralding the dawn of a new performance paradigm. These days, not so much, and it shouldn't be a surprise; the same thing happened with Sandy Bridge-E, last revision. Gamers are no longer willing to pay a huge mark-up for minimal returns, and the market now reflects that.

The upshot is: if you're running a desktop Sandy Bridge-era CPU, you don't need Ivy Bridge. If you're running older, and feeling the performance pinch, grab yourself the i5 3570K CPU and overclock to get yourself the best value on the market. If you're not comfortable with overclocking, but want the best performance, plonk down for the highest clock speed non-K processor that you can afford. A side note — Intel tells us it's no longer shipping K series processors with heatsinks. It's a savvy move, as those who buy K version processors will most likely buy their own aftermarket coolers anyway.

Chipsets ahoy!

It wouldn't be a new processor launch without a new chipset, and Intel's 7-series boards were available weeks before its processors. Good thing, then, that the socket hadn't changed; Sandy Bridge will happily work in any 7-series board. Ivy should work in prior LGA 1155 boards, as long as a BIOS update is made available.

It also means that people shouldn't have to update their aftermarket coolers. As an interesting aside, if you buy a K-series processor (indicating it's multiplier unlocked) this time around, you won't get a stock heat sink with it; Intel has realised that those who buy these will almost always go aftermarket.

So, what does the new chip bring in combination with the new board? DDR3 supported at 1600MHz instead of 1333MHz, up to four USB 3.0 ports (dropping available USB 2.0 ports from 14 to 10), two SATA 6Gbps ports, PCI Express 3.0 and Thunderbolt capability.

Although Intel's chipset supports four Intel USB 3.0 ports, we've seen a few motherboards already that only use two. Take note that Thunderbolt support doesn't mean that the port will appear on your board, either; it still requires an additional chip.

(Credit: Intel)

We say capability, because, at this stage, Thunderbolt is still managed by a separate chip. The first rash of motherboards we've seen have opted not to include it, no doubt due to a higher bill of materials (BoM) cost. Intel has reaffirmed that it sees Thunderbolt as the future, but, from our perspective, it's certainly a slow burn.

Some of the other stats could be seen as a halfway house. Why not go all USB 3.0, or all SATA 6Gbps? For Intel, it's pragmatic; people are unlikely, at this stage, to run that many devices simultaneously that take advantage of the bandwidth. Given that a platform these days tends to last three to four years in terms of performance relevance, it'll be interesting to see whether this view bears out.

It also gives a point of competition for board manufacturers, with each serving up additional speedy USB and SATA ports thanks to the likes of Marvell et al. Heck, Asus is even trying to make Universal Serial Bus parallel, device support willing.

Also expect to see UEFI become the norm during this generation, rather than the stock-standard BIOS. We're worried that companies will get wrapped up in trying to out-pretty each other, and forget the usability — hopefully, this won't be the case. While Intel's UEFI on its own DZ77GA-70K board does have some niggles, it also manages to provide incredibly useful information; like exactly what SATA port you have what device plugged in to, accompanied with a handy graphic.

Intel's board also came with an EFI shell, complete with tab completion and the ability to read NTFS drives and copy to FAT32 drives. It has limited capability, but, as an OS-less disaster-recovery option, it's a step in the right direction.

For now, there are three motherboard chipsets on the market: Z77, Z75 and H77. H77 tends to operate in the MicroATX space, doesn't support CPU overclocking and effectively has less PCI-E bandwidth than the other two. This is fine, as it's physically smaller and can't actually fit the extra slots required to use the bandwidth, anyway.

Unless there's a huge price-point difference, there's no point in Z75. All it does feature-wise is cut Intel's Smart Response tech, otherwise known as SSD caching. There are also B75, Q75 and Q77 chipsets, but these are business platforms, laden with V-Pro, anti-theft technology and the like. Given their bandwidth limitations, they'll likely only ever be found in pre-built business desktops.

In short, if you're going for the full desktop experience, there's no option but to go for Z77, which happily services both the ATX and MicroATX market.

Performance

We tested the Core i7 3770K on Gigabyte's Z77X-UD3H, as the supplied Intel DZ77GA-70K board was pre-production, and often unstable.

Choose a benchmark: Handbrake | iTunes | Photoshop | Multimedia | Cinebench Multi

The biggest performance benefits are when all four cores can be put to use, as evidenced by the Handbrake, multimedia multitasking (which includes Handbrake) and Cinebench benchmarks. Otherwise, the 3770K doesn't make much of a dent against the previous king of the hill, the 2700K.

So, what about this claimed doubling of graphics power?

Games performance

First, for reference, let's see how the original HD 3000 inside the 2700K did with our gaming benchmarks.

| Batman: Arkham Asylum | ||

| Playable on: | ||

| VERY LOW | ||

| settings | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 93 | 70 | 37 |

| 1366x768, 0xAA, Detail level: Low, PhysX off. | ||

| Metro 2033 | ||

| NOT PLAYABLE | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 51 | 26 | 10 |

| 1366x768, DirectX9, 0xAA, Quality: Low, PhysX: Off. | ||

| The Witcher 2 | ||

| NOT PLAYABLE | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 16 | 13 | 11 |

| 1366x768, low spec. | ||

| Skyrim | ||

| NOT PLAYABLE | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 47 | 31 | 24 |

| 1366x768, Detail: Low. | ||

Only Batman hobbles across the line with the lowest graphical detail — it's the only game that the HD 3000 is able to get above 30fps at its minimum frame rate. Keep in mind that Metro 2033's benchmark tends to skip at certain points, even with the most powerful hardware, making its minimum frame rates an unreliable indicator of decent gameplay — but even the average frame rate can't hit 30fps.

So what does the HD 4000 do for us?

| Batman: Arkham Asylum | ||

| Playable on: | ||

| VERY LOW | ||

| settings | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 116 | 83 | 36 |

| 1366x768, 0xAA, Detail level: Low, PhysX off. | ||

| Metro 2033 | ||

| NOT PLAYABLE | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 55 | 28 | 8 |

| 1366x768, DirectX9, 0xAA, Quality: Low, PhysX: Off. | ||

| The Witcher 2 | ||

| NOT PLAYABLE | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 19 | 15 | 13 |

| 1366x768, low spec. | ||

| Skyrim | ||

| Playable on: | ||

| VERY LOW | ||

| settings | ||

| FPS | ||

| Max | Avg | Min |

| 65 | 41 | 32 |

| 1366x768, Detail: Low. | ||

Not much. It does manage to bump Skyrim just into view, at least during the recorded intro sequence, anyway. One thing is certain: we're not seeing double improvement here, and it's still very much not a gaming chip.

The graphics still count

HD 4000 is still important, though. The most important thing is what it means to the industry as a whole: Direct X 11 is now entry level, and game developers can target it as a base instead of Direct X 9 or 10, despite the fact that no right-minded gamer would use integrated graphics, anyway.

There's also the matter of QuickSync, Intel's video-encoding accelerator. It has a limited application set, as far as compatibility is concerned, and it smacks of Nvidia's CUDA all over again. The sooner everyone commits to OpenCL, the better.

If you happen to have one of the compliant programs, though, there are real benefits. Converting a 720p XviD file to H.264 on the i7 2700K took one minute and 51 seconds with QuickSync off, and one minute and 15 seconds with it on. Upgrading to the 3770K saw those times drop to one minute and 47 seconds, and 59 seconds total, respectively. Yes, it almost halved our encoding time. We can only hope that it either sees universal adoption, or that all vendors make things easier by adhering to the one standard of video acceleration soon.

Of less virtue is Virtu, LucidLogix's technology that allows a discrete GPU to function through Intel's integrated graphics. While technology like this has existed on laptops for some time from both Nvidia and AMD, what Virtu brings to the table is the potential to give an FPS boost by pairing discrete and integrated. It uses a profile system: identify an exe, and, when it's being run, Virtu will enable itself.

The practicalities are different: all of the games in our test suite performed slightly worse than just our single Radeon HD 7870 with Virtu enabled, with the exception of Skyrim — as at that point, despite Virtu saying it was enabled, it was clear that the Radeon was no longer part of the performance chain. While we did see big performance boosts with a Street Fighter IV benchmark in a closed situation, we'd say that Virtu still has a long way to go before it matures. We're seeing similarities to when SLI and CrossFire first started out, so here's hoping that LucidLogix makes rapid improvements from here.

The verdict

If you need to update today, then there's no doubt that Intel's third-generation Core products are at the top of the pile. The benefits to the previous architecture are minimal, though; so if you're a Sandy Bridge owner, and don't feel the pressing need for Intel native USB 3.0 or SATA 6Gbps, there's not much here that will tempt you over.