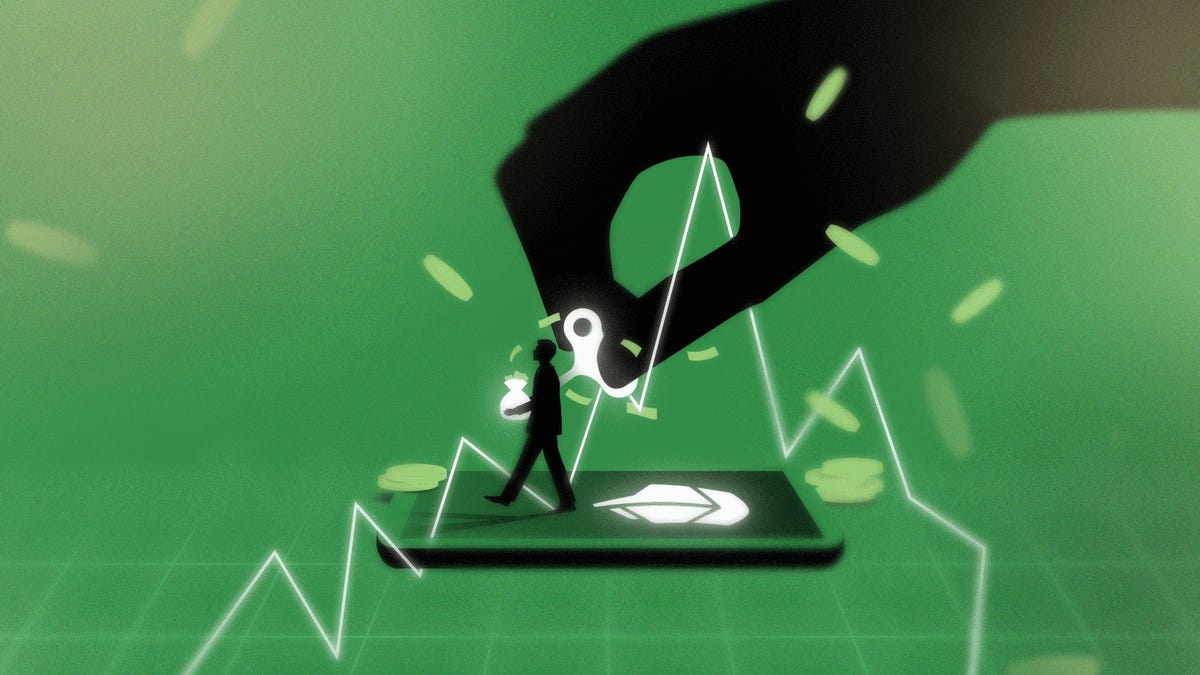

Robinhood's no-fee model has real costs: 'That is what scares me'

As the trading app inches closer to its IPO, concerns surface again over how the service could harm consumers.

During a heated congressional hearing in February, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez ripped into Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev, grilling the Silicon Valley executive over how his fee-free trading app makes money.

As Tenev appeared via Zoom before the House Financial Services Committee, the Democratic member of Congress, from New York, zeroed in on "payment for order flow." It's a financially wonky term for a controversial practice in the trading world that lets big investment firms pay brokerages like Robinhood for routing traffic to them. Then the firms make the trades on Robinhood's behalf.

Critics say the practice is harmful because it encourages a company like Robinhood to push its users toward more and more trades, spurring reckless investing. Ocasio-Cortez wanted Tenev to commit to paying those revenues to the app's users, instead of keeping them for itself.

"If removing the revenues that you make from payment for order flow would cause the removal of free commissions, doesn't that mean that trading on Robinhood isn't actually free to begin with?" Ocasio-Cortez said. "Because you're just hiding the cost."

The hearing was triggered by a bizarre saga that had shaken Wall Street a month earlier. Traders on Reddit had banded together on the subreddit r/wallstreetbets and ignited the stock of ailing video game retailer GameStop to an 800% surge. Robinhood, the app of choice for redditors making their wagers, was at the center of the frenzy. And now, as Robinhood inches closer to going public in one of the most anticipated tech IPOs of the year, the company is back in the spotlight. With the fanfare, though, comes renewed scrutiny of its business model.

Ocasio-Cortez's line of questioning underscores a common concern about Robinhood: that users aren't quite clear about what's going on or what they're really getting themselves into. It's not the only company to monetize its users. Google and Facebook, through their massive digital advertising businesses, suck up the data of people who use their services so marketers can target consumers more precisely. But the notion that "if it's free, you're the product" hits another level when the business model focuses not only on users' time and attention, but also potentially their life savings.

The fee-free app company was founded in 2013.

In addition to scrutinizing Robinhood for how it makes money, critics have slammed the company for promoting a cavalier attitude toward investing. They say the app exploits its users, turning trading into a mobile game, complete with animations and dopamine hits. And because of Robinhood's success, it's pushed more traditional competitors to adopt some of its practices.

"Everything they're doing is incredibly intentional," said Tara Falcone, founder of the financial education company ReisUp. "And that is what scares me."

Robinhood defends its business model and says it's opened up trading to people who otherwise wouldn't invest. "There will always be people who reject change. There will always be naysayers who say new ideas cannot work," a company spokeswoman said in a statement. "Robinhood refuses to accept the status quo, because if we were to stay the same, then we would be accepting a future where barriers to investing continue and where only a handful of people obtain the potential for financial freedom. The system failed to include millions of people who are now investing for the first time -- we're honored to serve them."

Payment for order flow

Founded in 2013 by Tenev and his former Stanford University roommate Baiju Bhatt, Robinhood was a pioneer in commission-free online trading. The product was tailored to serve its stated "democratize finance" mission and appeal to people with little experience in the stock market. Using the service, traders can get notifications and read market news. They swipe to confirm share purchases, which critics deride as a casual way to make major financial decisions.

Robinhood didn't invent payment for order flow. The practice has been around for decades, pioneered by Bernie Madoff, the investor notorious for Ponzi schemes, who died last month. Using the model, a brokerage like Robinhood makes money by directing trades to investment firms called "market makers," which pay fees to Robinhood for real-time information on stocks being bought and sold.

The order flow fees are small, but they add up. In the first half of 2020, the company generated more than $270 million from order flow revenue, according to regulatory filings. Robinhood's biggest partner in this area is the Chicago-based market maker Citadel Securities. Other partners include investment firms Two Sigma and Wolverine.

Robinhood denies criticism that encouraging a high volume of trades leads to reckless investing. The company cited an internal survey, saying half of the users who took the questionnaire said the app helps motivate them to save money. The company, however, didn't provide specific details about the survey's overall methodology. Robinhood also said it's introduced new educational resources in the app, like a course on how to define individual financial goals, as well as telephone support service for users.

At February's hearing, Tenev responded to criticism of its use of payment for order flow by emphasizing Robinhood is a "for-profit business." The company has a similar message on a page titled How Robinhood Makes Money on its website. "Earning revenue allows us to offer you a range of financial products and services at low cost, including commission-free trading."

Rachel Robasciotti, CEO of Adasina Social Capital, criticized payment for order flow in a hearing over the GameStop saga before a Senate committee in March, which was separate from the House proceedings. She couldn't comment specifically on Robinhood during an interview, but when speaking broadly about fee-free apps, she said such apps ultimately harm small traders because the companies aren't protecting them. "Who is really their customer? she said. "There's a deep lack of clarity."

Robasciotti said all the attention around payment for order flow from the GameStop drama is ultimately bad for fee-free apps. The business model works best when consumers are ignorant about how the company makes money, she said, but now that more people know, a level of trust has been broken. "It really puts long-term relationships with the consumer at risk," Robasciotti said. "That's the core of sustaining a business."

Indeed, the model rubs some users the wrong way. O'Neil Thomas, a 23-year-old actor from New Jersey, started using Robinhood about a week after the GameStop saga. He had no idea about the payment for order flow model. After CNET explained it to him last week, he called it "shady."

"I feel like they're not really vocal about that when signing up with them," he said. "Especially when it comes to trading stocks, you want to be as transparent as you can."

'Treating this like a game'

The app's detractors also say Robinhood uses emotion-tugging mechanics and features similar to video games in order to get people hooked on the service. The app used to shower the screen with digital confetti for certain milestones like a user's first trade, but the company changed up the design of its digital celebrations in March. New members are given a free stock of the company's choosing when they sign up. The danger, though, is that investing is complicated. Real money is at stake and critics say Robinhood doesn't do enough to make users aware of the consequences.

At worst, tragedy has struck. In June 2020, college student Alexander Kearns killed himself after seeing a negative balance of more than $700,000 in his Robinhood account, though some of his trades were incomplete. In a suicide note, Kearns named Robinhood, asking how it allowed a novice trader get into that position.

"How was a 20 year old with no income able to get assigned almost a million dollars worth of leverage?" the note read. "There was no intention to take this much risk."

Rep. Sean Casten, a Democrat who represents Kearns' Illinois district, told the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission in June that the app's documentation didn't do enough to explain the risks involved in trading. Robinhood later paid $65 million to settle with the SEC for failing to adequately disclose its revenue sources.

Then in December, securities regulators in Massachusetts sued Robinhood over its gamelike features. "Treating this like a game and luring young and inexperienced customers to make more and more trades is not only unethical," Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin said at the time, "but also falls far short of the standards we require in Massachusetts." Last month, the state sought to revoke Robinhood's broker-dealer license, prompting the company to sue to invalidate the case.

As Robinhood's IPO approaches, Falcone worries the problems with Robinhood's business model will only get worse. She's concerned the app will get even more aggressive in trying to increase trade volume as a public company, as it tries to reward shareholders with growth.

"They're incentivized to have their users trade, and trade frequently," she said. "They don't care whether their users actually make money or lose money."