Your Android phone is too damn nosy

If given the choice, people say they would deny nearly one-third of all permissions currently required to download apps to their Android phones.

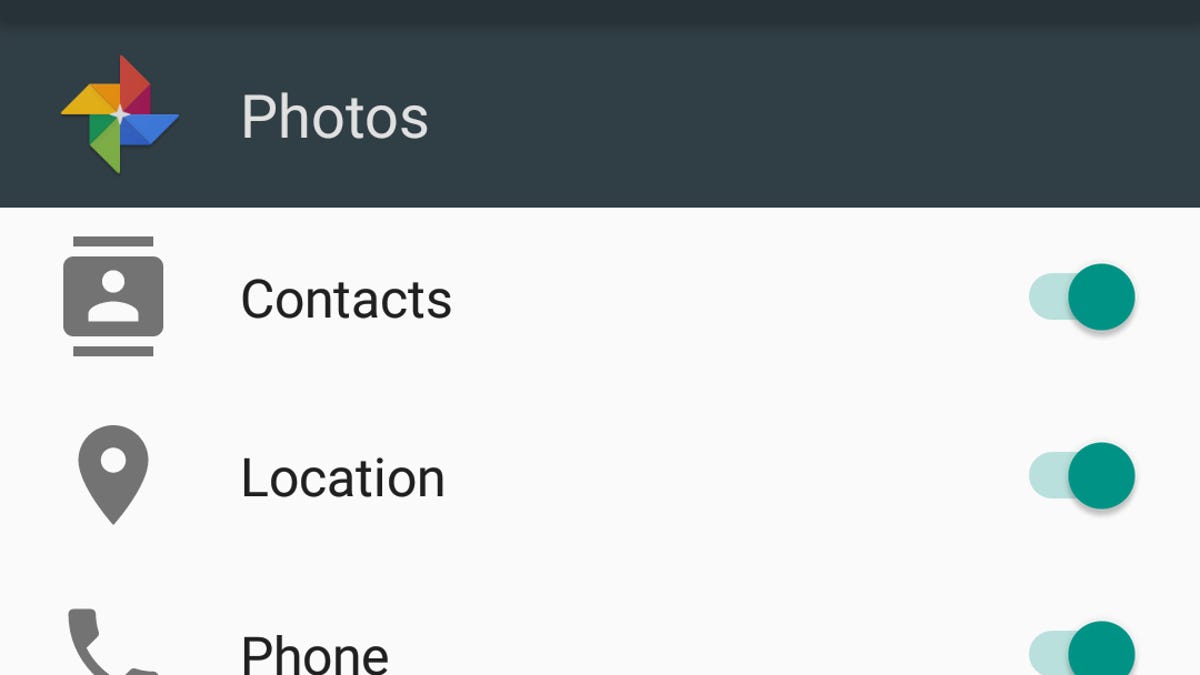

Permissions have been revamped for the Marshmallow operating system, but the software is still on less than 1 percent of Android phones.

Where are you right now? Can I see a list of everyone you know? Can I look through your photos?

Those are impertinent questions from any source, including your smartphone. So it's no surprise that people who use Google's Android smartphone software wish they could say "no" more often. That's according to a study presented Thursday at a Federal Trade Commission privacy conference in Washington, DC.

There's a catch, though, said study co-author Serge Egelman. People are already overwhelmed by the amount of permissions and privacy policies they accept on their devices and the Internet. So rather than unleashing a plague of pop-ups onto our phones, researchers believe one solution is to make it easier to fine-tune privacy settings in one fell swoop.

The problem underscores how exhausting it is for us to manage our privacy, let alone figure out what we want our phones to do. It also hearkens back to critiques other companies have faced when grappling with security issues for their respective devices.

Remember Windows Vista? Microsoft's PC operating system, publicly released in 2007, was roundly criticized for asking people too often for permission to do even basic computer functions. Apple joined in on the fun, creating an ad that mocked Vista as an overbearing security guard.

On Android phones, people have faced an all-or-nothing approach. They could accept all permissions when they download the app or nix downloading it at all. Google is addressing the concerns of Egelman and others with its Android Marshmallow operating system, which lets people sign off on more specific permissions before installing an app. Marshmallow was released in October but is running on less than 1 percent of Android phones so far, according to Google.

So if you want your flashlight app to access your camera so it can control the LED flash but not let it access your contacts, you might be able to do something about it when you eventually get Marshmallow.

Egelman said that up to now people have been used to and resigned to just tapping "yes" on permissions so they can use an app. But the study, conducted by the University of British Columbia and the University of California at Berkeley, showed that 80 percent of people would have said "no" to at least one permission request if they'd been given the opportunity. What's more, the average participant wanted to say "no" to nearly a third of all the permissions their phone has demanded in order to run apps.

Egelman said a big question is, "How do we give consumers control over the things they really care about without overwhelming them?" He suggested that learning the basics of what people care about and then streamlining their permissions accordingly would be the best solution.

That point was echoed by researchers throughout the day. Showing people less information about security permissions but tailoring their permissions to their preferences could make them more willing to think about how much personal information their phone is tracking.

Other ideas to help the medicine go down include security prompts that look like nutrition labels, so people can see at a glance what's going on instead of reading mind-numbing legalese. Others suggested more automated settings, based a person's general preferences.

Google did not respond to a request for comment.

Egelman summed up the conundrum by noting that "choice is great" but "attention is a finite resource."

Update, 8:52 p.m. PT January 14 and 4:40 a.m. PT January 15: The report's findings and the status of Marshmallow have been clarified.