Shrinking 'hot Neptune' could explain how other Earth-size planets form

Astronomers spy quickly evaporating planet GJ 3470b, which could help solve an odd mystery about distant worlds.

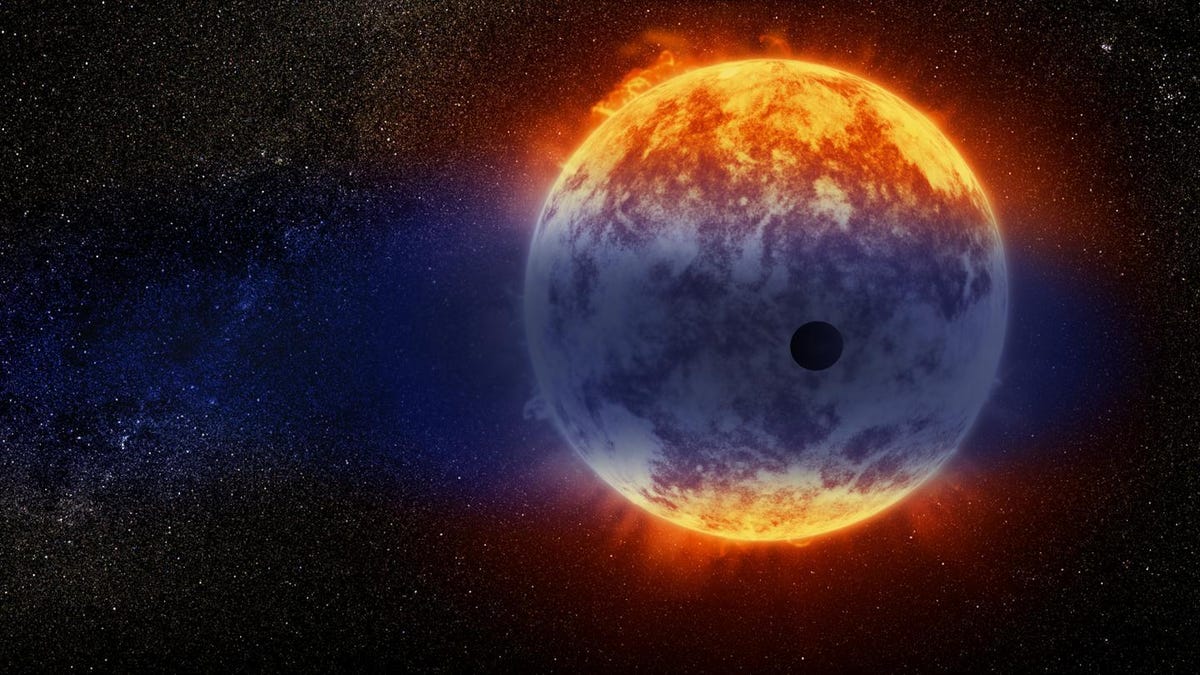

This artist's illustration shows a giant cloud of hydrogen streaming off a warm, Neptune-size planet just 97 light-years from Earth.

In the couple of decades scientists have been able to spot planets beyond our solar system, a weird mystery has emerged. Among the worlds orbiting very close to their stars, the medium-size planets seem to be missing.

But the fascinating new discovery of a so-called "hot Neptune" exoplanet that's quickly evaporating might provide a key clue to what's going on. And solving the mystery could help us better understand how distant planets evolve to become a little more like ours.

The catalog of planet-hugging, hot exoplanets discovered so far includes lots of gigantic planets like Jupiter and many smaller, rocky planets often referred to as "super-Earths (planets up to 1.5 times Earth's diameter)," but there are far fewer medium-size worlds comparable to our system's own Neptune or Uranus. This gap in the distribution of distant worlds is often called the "hot Neptune desert."

A new report published Thursday in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics bolsters one possible explanation. It details observations of the planet GJ 3470b, a hot Neptune that's shrinking 100 times faster than a previously discovered disappearing planet of the same size.

"This is the smoking gun that planets can lose a significant fraction of their entire mass. GJ 3470b is losing more of its mass than any other planet seen so far," co-author and Johns Hopkins University physics professor David Sing said in a statement. "In only a few billion years from now, half of the planet may be gone."

That's not a typo: "Only" a few billion years is a relatively short time when talking about the entire life cycle of a planet. The researchers estimate that over a third of the planet's mass may have evaporated already.

The idea here is that planets that orbit very closely to their stars are obviously hotter and can have the outermost layer of their atmospheres blown away by evaporation. So the reason so few hot Neptunes have been seen could be because they're rapidly evaporating and transforming into smaller super-Earths.

Larger, Jupiter-like giant planets, on the other hand, may be more dense and possess a stronger gravity that allows them to better hold on to their atmospheres.

"This could explain the abundance of hot super-Earths that have been discovered," said co-author and University of Geneva professor David Ehrenreich.

Observing the evaporation of a planet isn't easy, but the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will offer more sensitive instruments that'll allow astronomers to take a closer look at these boiling, deflating giants.

NASA turns 60: The space agency has taken humanity farther than anyone else, and it has plans to go further.

Taking It to Extremes: Mix insane situations -- erupting volcanoes, nuclear meltdowns, 30-foot waves -- with everyday tech. Here's what happens.