What can a red balloon tell us about self-control?

Researchers watch the light show that happens in the brain when study participants are faced with a risky decision in a nondescript video game.

As video games go, Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) is probably one of the least compelling ever created. There are no zombies, no deserted hospitals, no slick race cars. All it has is a red balloon on a white background that users pump up by clicking a button that looks like it was developed for (and maybe with?) the original Windows operating system.

Still, BART may have some interesting things to tell us about how the brain works, specifically in terms of risk-taking behavior.

You see, the game works by having you click that boring button to shoot a burst of air into the balloon. For every click that inflates the balloon without it popping, you "win" 5 cents (I still haven't figured out how to collect my stash from the developers). Pump up the balloon too much though, and you lose the cash you've accrued in that round.

So how does this provide information about our gray matter?

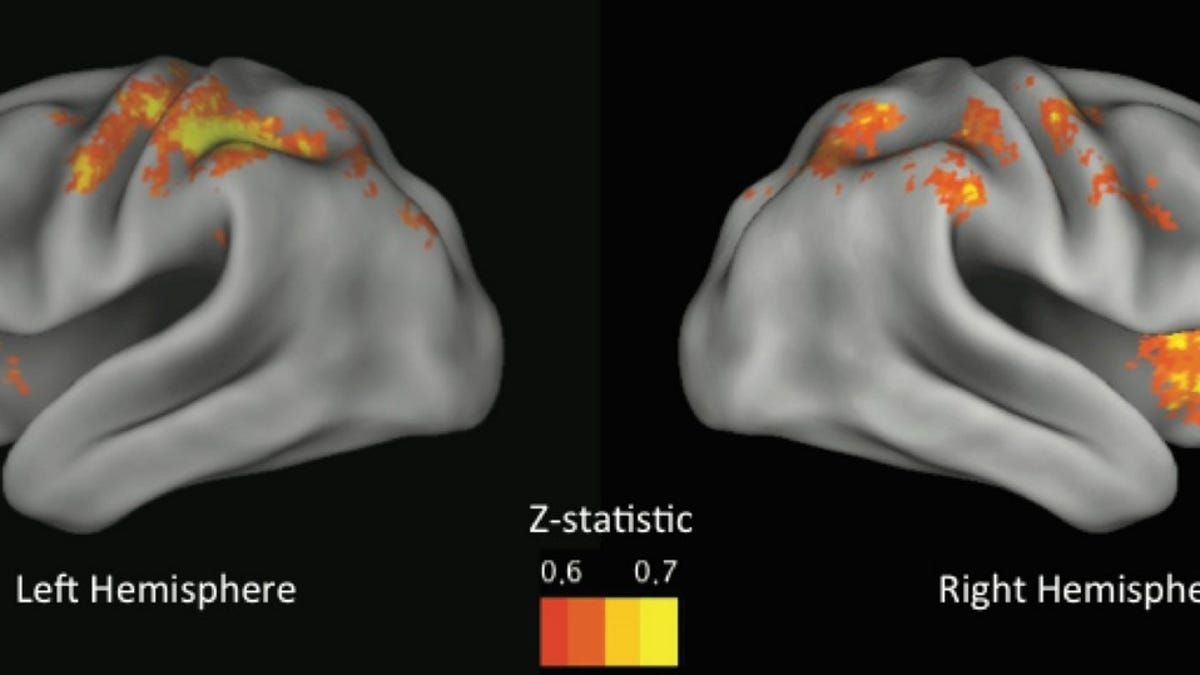

Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin (and UCLA and a collection of other universities and medical centers) put 108 BART players in an MRI machine while they were clicking. The researchers then watched to see which parts of the brain were activated as participants made a risky choice, like pumping up the balloon too much.

The scientists concluded that we engage in risky behavior (like telling ourselves that we're just going to play World of Warcraft in the middle of the day for "just five minutes"), not because the reward centers in our brains are overactive, but because we have trouble putting on the brakes.

In other words, it's not that the reward centers of the brain lit up too much when study participants went for that extra pump, it's that the sections of their brains related to self-control simply didn't light up enough.

Interestingly, the researchers employed a software program to look for patterns in the brain prior to the risky decision making. Then, they asked the software to "watch" the brain of other study participants and try to predict what action they would take solely based on the lit up parts. The software got it right 71 percent of the time.

"These patterns are reliable enough that not only can we predict what will happen in an additional test on the same person, but on people we haven't seen before," Russ Poldrack, director of UT Austin's Imaging Research Center and a professor of psychology and neuroscience, said in a statement.

Because of the predictive nature of the software, the researchers believe their system could help evaluate the likelihood that a criminal would commit another crime (is anyone else thinking "Clockwork Orange" here?). They also hope to find out through additional research how factors like fatigue, hunger, or peer pressure affect how we think about risky decisions.

The results of the research appear this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).