Turns out investing in venture-capital funds isn't a great idea

That's a generalization of findings made by Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, an organization designed to promote entrepreneurship that invests in venture capital funds.

In order for venture-capital firms to invest in startups, they need funding from institutional investors. In many cases, such investors are happy to drop some cash in a fund. But a new study warns that doing so might not be the best idea.

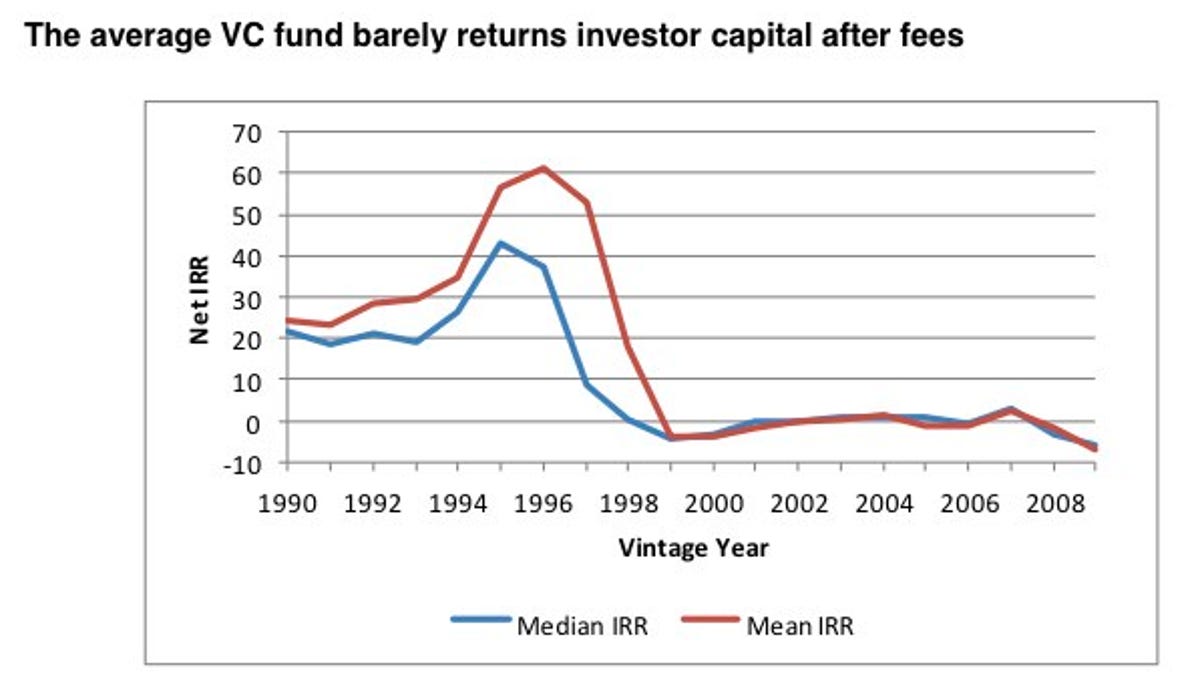

The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, an organization that promotes entrepreneurship by investing in venture-capital funds, found things might not be as bright as some firms would have investors believe. In fact, the organization found that over the last 10 years, the vast majority of venture-capital funds have failed to outperfom the public stock market. In the last 15 years, venture-capital funds haven't even been able to return to investors the cash they've invested.

The Kauffman Foundation certainly has a solid grip on what's happening in the venture-capital community, thanks to its more than 20 years of experience investing in nearly 100 funds. The foundation has $1.83 billion in endowment, including $249 million invested in venture and growth funds.

Interestingly, Kauffman found that time is a major issue for institutional investors. In the beginning, funds "inflated early returns" to make it easier to raise cash in subsequent rounds, Kauffman claims. From there, "historical performance" can only be characterized as "poor."

In addition, Kauffman found that just 20 percent of venture funds it studied have been able to generate a return of more than 3 percent annually. And out of that group, half of them began investing in startups before 1995. All told, net of fees, Kauffman is being paid just 1.31 times the cash it has paid out.

"The foundation found that the most significant excess returns earned from venture capital occurred in funds raised prior to 1996, and those funds averaged $96 million in committed capital," the organization said yesterday in a statement. "Many of those successful funds led managers to raise successively larger funds; which significantly eroded returns and maximized general partner profits through fee-based income at the expense of limited partner success."

Kauffman's findings underscore just how little of an impact major successes can have on the venture-capital space. Companies like Google, Yahoo, eBay, and many others have come along and made investors significant cash. Facebook's pending IPO will do the same. But in far too many cases, according to Kauffman, failures yield no return to investors. What's worse, the organization argues, too much cash is changing hands, and not enough is being charged for it by institutional investors.

So, what's the takeaway? Simple: venture-capital firms are having little trouble receiving funds from institutional investors looking for a quick, easy profit. But over the last decade, especially, few investors have actually been seeing a positive return on that investment.

"The result is that institutional investors end up paying general partners -- who typically commit only 1 percent of partner dollars to a new fund while LPs commit the remaining 99 percent -- quite handsomely to build funds, not build companies," Diana Mulcahy, director of private equity at the Kauffman Foundation said yesterday in a statement.

Given that, Kauffman says it will no longer spread its cash around. Instead, it'll become "disciplined investors in only a handful of VC funds."

Here's a link to the full Kauffman report (PDF).