There's a radio telescope on the far side of the moon now

It's hoping to listen for signals from the universe's infancy.

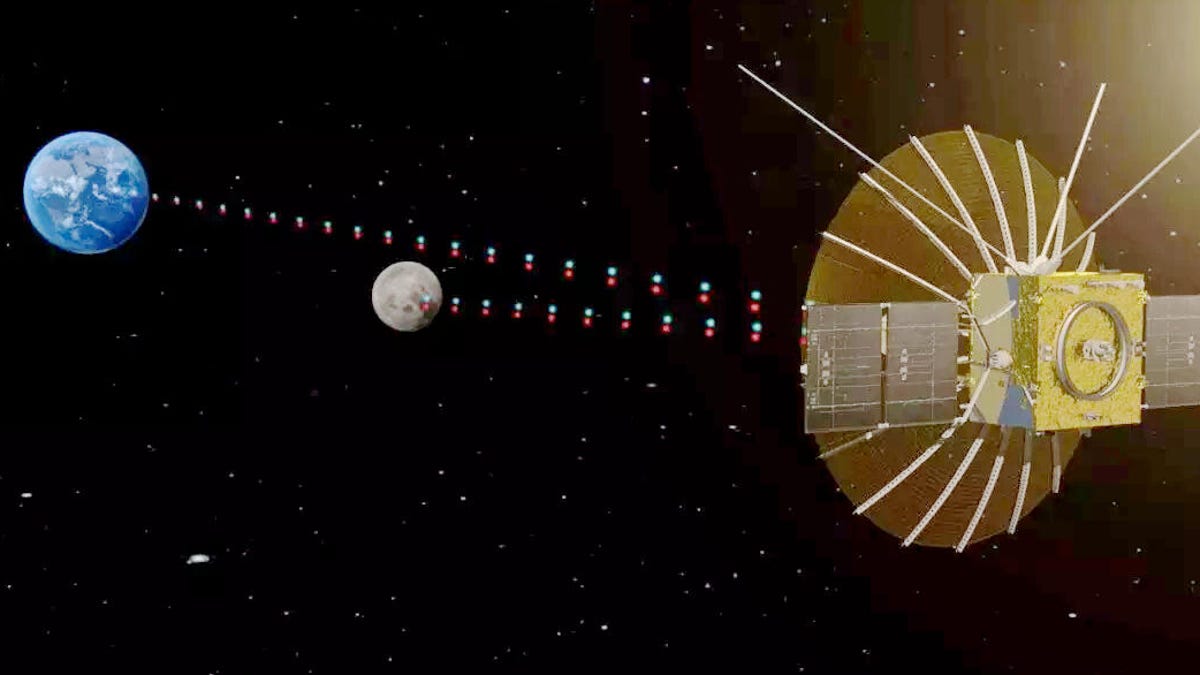

NCLE is mounted on the Chinese QueQiao relay satellite orbiting behind the moon.

It's been a dream of countless astronomers for generations: a telescope located on the far side of the moon, without radio transmissions, an atmosphere and all the other things on Earth that can get in the way of a clear view of deep space.

Good news, space fans: The dream finally came true last week when the antennas on a Dutch-Chinese radio telescope unfolded behind the moon.

The Netherlands-China Low Frequency Explorer is part of China's Chang'e 4 mission that sent a lander and rover to the far side of the moon along with a satellite named QueQiao. NCLE is a radio telescope made up of three long antennas mounted on QueQiao that's designed to listen for low-frequency signals.

The goal is to look for weak radio signals originating from a period just after the Big Bang that's often referred to as the dark ages by cosmologists. Such signals are blocked by Earth's atmosphere, which is why NCLE is ideally suited for hanging out behind the moon.

This series of three photographs was taken during the unfolding of an antenna on the QueQiao satellite. The antenna is the black-and-white rod pointed away from the camera.

The NCLE team had to wait for over a year to unfold its antennas, which was longer than initially planned, while QueQiao was busy working as a communications relay for the lander on the lunar surface. Spending more time than expected hanging in space behind the moon seems to have affected NCLE. It had a hard time completely unfolding its antennas.

The Netherlands-based team decided to first collect data using the partially unfolded antennas, which should allow for detection of signals from about 800 million years after the Big Bang. Later they may try again to unfold them completely to target data from closer to the dawn of the universe.

"We are finally in business," NCLE science leader Heino Falcke said in a release. "The first data will reveal how well the instrument truly performs."

NCLE will first target the sun and Jupiter, which are thought to emit strongly at low frequencies, but they'll also be listening for signals from much deeper in space and time.