Tech firms warn privacy bill will harm economy

A group representing Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and AOL warns that a proposal to regulate data collection and use practices will "hinder" e-commerce and cause economic harm.

A new privacy bill introduced in the U.S. Congress this week would have serious unintended consequences and could even harm the nation's economy unless its Democratic sponsor rewrites it, Internet industry representatives warned Thursday.

The proposal, introduced by Rep. Bobby Rush of Illinois, slaps fines of up to $5 million on businesses and even some individuals unless they abide by a complex set of new regulations to be administrated by the Federal Trade Commission.

That legislation "would turn the Internet from a fast-moving information highway to a slow-moving toll-road," Michael Zaneis, vice president of public policy at the Interactive Advertising Bureau, told Rush's committee on Thursday. "Such a move would hinder, not facilitate e-commerce." The group's board members include representatives of Google, Facebook, Microsoft, AOL, Comcast, Amazon.com, Fox Interactive, and CBS Interactive, which publishes CNET.

Zaneis took pains to compliment some portions of the legislation (H.R. 5777) drafted by Rush, the chairman of a House consumer protection subcommittee. But, Zaneis added, "our industry is a major component of the national economy," and burdensome regulations would retard its growth and cause economic harm.

The 55-page measure arrives as companies' data collection and use practices are being subjected to increasing scrutiny on Capitol Hill, in part because of high-profile privacy missteps by Facebook and Google that have drawn criticism from some politicians. While it's unlikely that Rush's proposal will become law this year--there's little legislative time left before the November elections--a favorable welcome would give it momentum for 2011.

Rush's bill, called the Best Practices Act, applies to any "person" or business that stores personal information, including someone's name, mailing address, e-mail address, and phone or fax number. That person must provide, if requested, "access to" information stored about others.

There is an exemption for small businesses, but not if they hold 15,000 or more names, e-mail addresses, or other personal information in their records. The language is broad enough to apply to local retailers, small businessmen like plumbers and carpenters, and even individuals who have a sufficient quantity of e-mail addresses on their PCs. (The free-market Competitive Enterprise Institute notes that numerous "small businesses and nonprofits across the nation routinely store basic details, such as phone numbers and e-mail addresses," with little in the way of privacy catastrophe.)

That approach, including everyone from eBay sellers to supermarkets and general contractors, amounts to a scattergun approach rather than a rifle bullet aimed at less scrupulous companies. That's why the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the nation's largest business advocacy group, took an even more critical stance during Thursday's hearing.

Jason Goldman, an attorney representing the chamber, said his organization has "strong concerns with the bill as currently drafted."

Unless rewritten, the measure would harm the interactive advertising industry (responsible for $300 billion in economic activity last year, according to the IAB) , Goldman said. "The chamber has serious concerns about private right of action" as well, he added, referring to the portion of the bill that allows anyone to file lawsuits for actual damages of up to $1,000 and punitive damages with no set limit.

For his part, Rush signaled that he was opening to amending a few portions of his bill. But he also said that "I'm also determined that we need to move forward" and avoid any "unnecessary delay."

While the future of the legislation is anything but certain, it's already exposing a fault line between business representatives and liberal advocacy groups that has been mostly dormant in the last few years. Recently, instead of sparring with one another, groups including the ACLU, the Center for Democracy and Technology, and Consumer Action joined with AT&T, Google, Microsoft and others to create a coalition supporting limits on police surveillance.

Now some of these same advocacy groups are lobbying for--or at least saying kind things about--legislation opposed by the Internet industry. CDT President Leslie Harris called it an "essential" building block "for a modern and flexible consumer privacy law," while Ed Mierzwinski of U.S. PIRG--an advocacy group founded by Ralph Nader--believes the Rush bill doesn't go far enough.

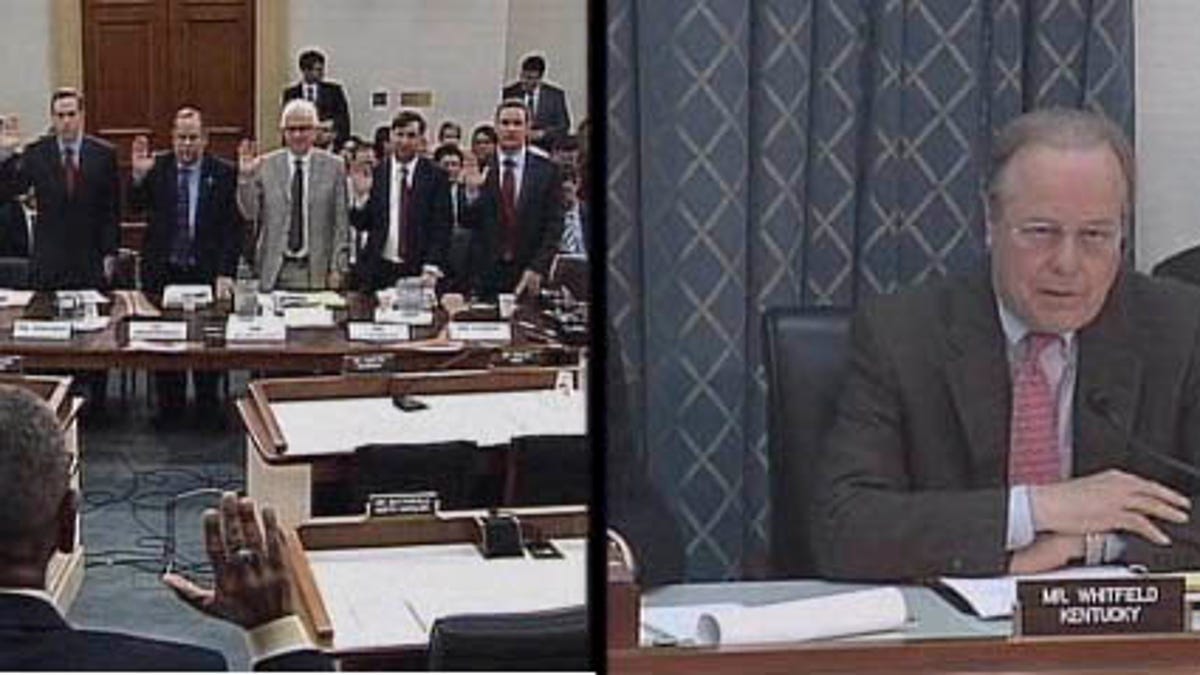

Like Net neutrality, this could devolve into a partisan spat. Kentucky Rep. Ed Whitfield, the panel's senior Republican, said that by acting hastily, Congress could force businesses "to abandon or severely curtail legitimate practices that benefit consumers." In addition, he said, "we have to be very careful about the latitude we give the FTC in this area."

The Rush bill isn't the only proposal before Congress at the moment. Rep. Rick Boucher, a Virginia Democrat locked in a contested reelection bid in a conservative district, announced his own so-called privacy discussion draft in May.

As soon as Boucher's proposal became public the reaction was surprisingly uniform: everyone hated it. Liberal special interest groups announced they were "disappointed" that Boucher didn't slap even more regulations on Internet businesses. Free-market think tanks panned it for going too far. And industry groups said it was far too broad as currently drafted.

In some ways, the new Rush bill is narrower. It treats "sensitive" information including race, religion, and ethnicity as different from standard personal information. It generally keeps opt-out as a default. It lifts the number of records required to trigger the regulations from 5,000 to 15,000. It holds out the possibility of an FTC-approved safe harbor for some businesses that self-regulate.

On the other hand, Rush hopes to mandate new "physical safeguards" that apply to anyone holding 15,000 or more records, encourage civil litigation over possible violations, and impose new regulations such as saying business "shall retain such data only as long as necessary to fulfill a legitimate business purpose or comply with a legal requirement."

Rush's legislation is called the Building Effective Strategies To Promote Responsibility Accountability Choice Transparency Innovation Consumer Expectations and Safeguards Act, or Best Practices Act of 2010.