How a startup's tiny dots could lead to better smartphone photos

With tech called quantum dots, InVisage promises to surpass the limits of today's image sensors and vastly improve digital photos and videos. The first devices with its technology should arrive in early 2016.

MENLO PARK, California -- The future of photography is arriving here with a steady drip, drip, drip.

At least that's the plan for InVisage Technologies, a 75-person startup that hopes its exotic new material known as quantum dots will dramatically improve smartphone cameras when it arrives in devices in the first quarter of 2016.

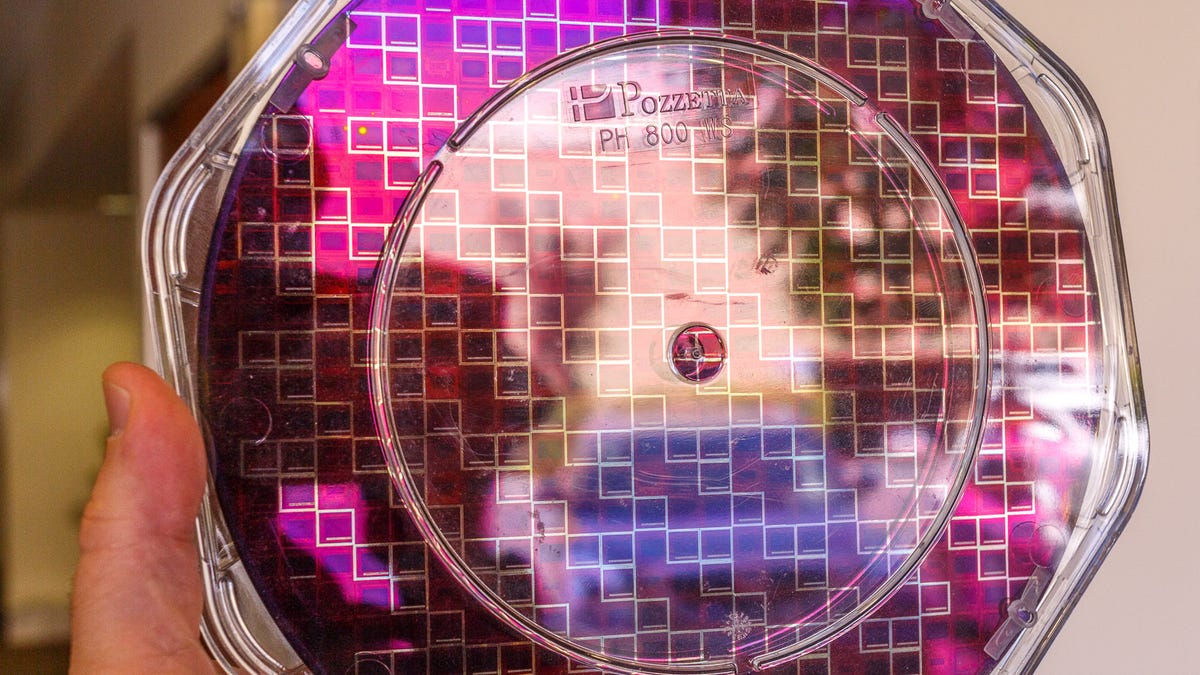

In an exclusive look into its operations tucked inside a drab office building in the heart of Silicon Valley, InVisage showed CNET how it makes the tiny particles in an ultra-clean lab where staff wear coats, gloves, booties and hairnets to protect the material from contamination.

InVisage's product, the QuantumFilm image-sensor chip, begins with a chemical reaction that fills a vial with an inky black liquid drop by drop. Concentrated, 1 fluid ounce is enough to make enough image-sensor chips for 10,000 cameras. The quantum dots themselves are less than 5 nanometers wide -- small enough that more than 20,000 of them side by side would be only as wide as a human hair.

Chips with the light-detecting layer of quantum dots will outdo today's image-sensor technology, Lee said. First, their better dynamic range can handle highlights and shadows better, letting you avoid the glare of overexposed faces in the sun while still discerning the subjects in the shade. Second, a fast-acting "global shutter" avoids the Jello-wobble effect that hurts today's videos taken when the subject or camera is moving. Last, QuantumFilm-based cameras can be made thinner so phone makers can avoid the protruding camera lens present even on today's top-end phones like Apple's iPhone 6S and Google's Nexus 6P.

Cameras are crucial to smartphone-powered activities like sharing photos with friends and family. We post more than 80 million images a day on Instagram alone. But image quality often falls short. Look no farther than Apple's to see how smartphone makers push camera improvements to try to stand out in a crowded market.

"Image sensors are critical to smartphones," ranking third in importance after battery power and the display, said InfoTrends analyst Ed Lee. "People continue to take more and more photos, and it's going beyond just memory keeping and social sharing" as people use phones to search, scan and try augmented reality apps that add a digital layer to the real world.

'Extremely difficult task'

InVisage won't have an easy time meeting its ambitions. It's going up against giants like Sony, which according to analyst firm IHS, accounts for about 42 percent of the $9.6 billion image-sensor business. Success requires increasing production to thousands of chips a day while maintaining quality. And it's been tough developing InVisage's technology. In a 2010 interview with CNET, Lee said he expected QuantumFilm image-sensor chips to arrive in 2011.

"Succeeding in the market will be an extremely difficult task for InVisage," said IHS analyst Brian O'Rourke. "The

Even if it took five years longer than hoped, InVisage is fledging from the nest now, with help from more than $100 million raised in venture capital.

"While we've been taking longer to come to market than we originally predicted, this is brand-new technology," said Lee, who previously worked at OmniVision.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) fabricates most parts of each QuantumFilm chip, but InVisage completes the job by adding the quantum dot layer. Lee wouldn't identify which companies are buying its chips but said they are "aggressive early adopters...looking for a way to differentiate."

Initially, InVisage expects to charge smartphone makers the same price as the latest silicon-based sensor technology. In the longer run, it expects to lower manufacturing costs.

InVisage is starting with smartphones but plans to power traditional still and cinema cameras, too.

"We have high interest in the high-end space," Lee said. "It's a personal goal of mine to get our technology into those hands." High-end products have big marketing value for mainstream products, he added.

Quantum whats?

Today's image sensors are specialized computer chips with a layer of silicon that is sensitive to light. The more light that strikes each of millions of pixels on the image sensor, the more an electrical charge builds up for that pixel. Circuitry converts that charge into image data.

QuantumFilm uses a super-thin layer of its light-sensitive quantum dots instead of silicon. Each dot is made of a semiconducting material that conducts electricity or not depending on its environment. Different dot sizes are sensitive to particular colors of light.

One of the biggest quantum dot advantages is better dynamic range -- the span between the darkest shadows and the brightest highlights. QuantumFilm can record image details at brightness levels that would overwhelm a silicon sensor. Specifically, QuantumFilm remains sensitive to detail even as it absorbs up to eight times as much light, or up to three stops in photography terms. That translates into a sensor that better captures reality without resorting to multi-exposure "HDR" high dynamic range tricks.

QuantumFilm also has a useful feature called global shutter that reads each pixel of video data simultaneously. That can bring realism to videos otherwise spoiled when the camera holder or subject is moving.

Another perk: Because quantum dots are laid down in a continuous film, the number of pixels on a sensor isn't baked into the hardware. A smartphone could be set to capture images with a maximum number of pixels for fine detail then changed to a smaller number of larger pixels for better low-light performance.

Digital image sensors have evolved slowly for decades, starting with technology called CCD (charge-coupled devices) before moving to conventional technology called CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) chip manufacturing that's better suited to video and to use in smartphones. The most recent development has been backside illumination (BSI), which flips CMOS image sensors like pancakes so light shines on the back of the chip and electronic components won't block light.

Lee thinks quantum dots are the next step for the entire industry in the quest for better image quality. "There's nothing else out there," he said.