Spacesuit of the future could power gadgetry with body heat

Researchers at Kansas State are investigating how the difference in temperature between body heat and a spacesuit's cooling garment could run the suit's electronics.

Wondering what's next in wearable electronics? Fitness trackers like the Fitbit Force and the Nike+ FuelBand SE may be fine for the earthbound, but for the astronauts among us, NASA's working on a different kind of fashionable circuitry.

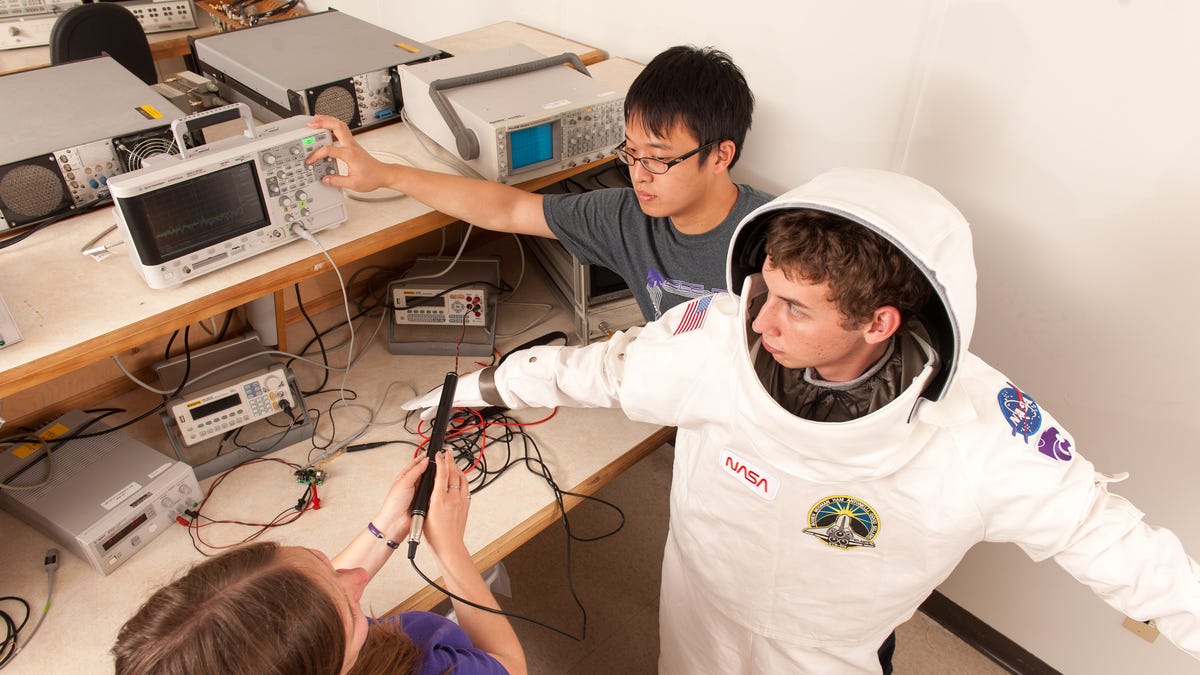

At Kansas State University, researchers are just over two years into a three-year, $750,000 NASA grant to turn current spacesuits into even better readers of astronauts' vital signs -- and on top of that, make use of the inner workings of the suits themselves to power radios and other embedded electronics.

"Right now the spacesuits pretty much only measure heart rate," said William Kuhn, professor of electrical and computer engineering and part of the spacesuit team, which includes engineering professors and a dozen-plus students. "In this project we're focused on EMGs [electromyography] that can monitor muscle activity. The biggest problem that the astronauts have when they're doing their work is they get very fatigued because of the pressure in the suits, so we're focusing on being able to predict when they're going to be fatigued so we can help them reorder their tasks in space."

Monitoring basic vital signs may sound simple, but the researchers have to take into account the way astronauts' bodies react to being in space -- the decreases in muscle mass and bone density, the potential changes in visual acuity, and so on. So even basic vitals monitoring has to adjust for these differences. The researchers are working on a wide array of wearable body area networks, including electromyographic sensors to measure muscle activity, accelerometers to measure movement, pulse oximetry sensors to measure heart rate and blood oxygen saturation, and respiration belts to measure breathing rates.

Kuhn said the team has ascertained that it can monitor muscle activity and will be able to predict fatigue, and that it can do both wirelessly. But because a real spacesuit's price tag of $13 million would make even the likes of the Hollywood elite blush, the students are working with a replica built by a master's student for a few thousand dollars, so they won't know for sure if their tech is working properly until they go in and test it on actual spacesuits. Kuhn said he hopes to do that in early 2014.

And here's a wrinkle of astronaut fashions that makers of smart bras and fitness shirts for earthlings don't have to worry about: the oxygen-rich interior of a spacesuit, which is a dangerous place for batteries. That has the Kansas State team working to develop entirely new energy-harvesting tech -- using the difference in temperature between body heat and the spacesuit's cooling garment to power the suit's electronics. If it proves feasible to monitor vitals using the suit itself, sans batteries, perhaps someday the tech will trickle down to our more earthly pursuits, such as powering battery-less MP3 players while jogging.

Not that any of this is going to be available next year. "Our goal is to take the technologies that we're developing and work with NASA to hopefully get those infused into missions of the future, but [in space research] these things don't happen until well down the road," Kuhn said. "Missions like probes to the outer planets will be 10 years in the making. So we're doing fundamental research to enable future astronauts to do the kind of work they need to do in the year 2020 or 2030."

And so it continues. Existing wearable medical sensors inform ones that work in outer space, and that tech will in turn be used to advance what we wear on planet Earth. All so that we may, of course, live long and prosper.