Senators, states beat up on Real ID plans

Homeland Security has postponed rollout of the new driver's license standards, but some politicians worried about cost and privacy still favor killing the controversial law.

WASHINGTON--Democratic and Republican senators alike on Tuesday once again piled criticism upon forthcoming Real ID requirements, with some renewing calls to repeal the law for which many of them voted years ago.

It's a familiar refrain for the Senate's Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, whose members made similar remarks at a hearing around this time last year.

Senators Daniel Akaka (D-Hawaii) and George Voinovich (R-Ohio), who presided over a Tuesday subcommittee hearing revisiting the topic, said they remain particularly troubled by Real ID's multibillion-dollar price tag for state governments. Akaka and others also voiced worries about the mandate's privacy and civil liberties implications.

"The massive amounts of personal information that would be stored in state databases that are to be shared electronically with all other states, as well as the unencrypted data on the Real ID card itself, could provide one-stop shopping for identity thieves," Akaka said at the hearing, where senators heard from Homeland Security assistant policy secretary Stewart Baker, state government representatives, and civil liberties activists.

Akaka, for his part, said he will continue to push for passage of the Identification Security Enhancement Act, which he introduced last Feburary. That bill would yank Real ID and replace it with a "negotiated" rulemaking process that was proposed before Real ID was glued onto an emergency Iraq war spending bill that passed unanimously in 2005. Republicans John Sununu and Lamar Alexander and Democrats Patrick Leahy, Jon Tester, and Max Baucus also support the bill, as do influential state officials and civil liberties groups, but it's unclear whether it has the momentum to go anywhere this year.

Meanwhile, the Department of Homeland Security has pushed ahead in its defense of Real ID, as necessary to prevent terrorists, criminals, and illegal immigrants from successfully obtaining and using fraudulent driver's licenses.

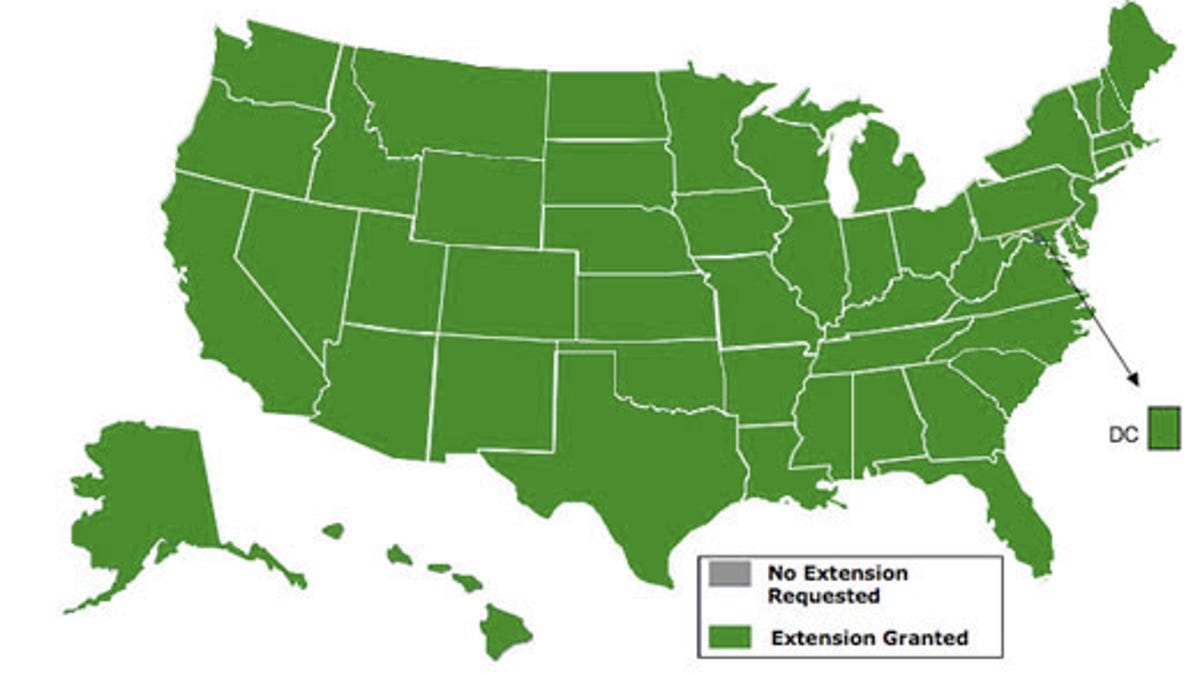

But the department effectively delayed obligations to begin complying with its rules until at least the end of 2009, granting all 50 states--even those that had passed legislation rejecting the federal mandate--and the District of Columbia initial deadline extensions. Without those extensions, residents of states without Real ID compliant licenses would have encountered difficulties boarding airplanes and entering federal buildings come May 11.

"While these extensions have averted a near-term crisis, they do not resolve other problems with Real ID," said Sen. Susan Collins, the Republican ranking member of the Senate Homeland Security Committee.

Who who protects the data, and who pays?

Baker endured repeated questions about the cost of the program, particularly from committee Republicans. He said "hundreds of millions of dollars have been made available" already for Real ID conversion projects, which, under Homeland Security's revised estimates, are expected to cost about $4 billion over the next decade. But a number of senators said they didn't think that funding was sufficient.

Donna Stone, a Delaware state representative and president of the National Conference of State Legislatures, and David Quam, a lobbyist for the National Governors Association, cast doubt on Homeland Security's cost estimates. They said that because of lingering uncertainties surrounding Real ID's requirements, the true costs are difficult to project but likely exceed Homeland Security's estimates.

Homeland Security put states in a tough spot by dangling the prospect of a May deadline that might inconvenience their residents, Quam said. The position of state governors is that "Real ID has to be fixed, it has to be workable, it has to be cost-effective, it actually has to increase the security of driver's license systems, and it has to be funded" by the federal government, he said.

Perhaps the most blistering critique of Real ID on Tuesday came from Tester, who called the program "the worst kind of Washington, D.C., boondoggle." He suggested it was curious that his home state had been granted a deadline extension, even though its attorney general had told Homeland Security that state law did not authorize Montana to implement Real ID, and the state legislature won't even meet again until next January.

"I am pleased that Montanans were not arbitrarily penalized under the law, truthfully," he told Baker, "but I really fail to see what this exercise actually accomplished other than to leave the details of Real ID to the next administration."

Baker said Homeland Security has tried to be flexible by giving extensions to states like Maine and Montana that said they're implementing certain security features in their driver's licenses "without insisting on some kind of pledge of allegiance to Real ID."

Baker also encountered questions, mainly from Democrats, about the lack of detailed security rules under Real ID.

Akaka asked why Homeland Security didn't set out specific security requirements for the databases that states will share. Baker said the agency is requiring states to have "security plans" for their data but wanted to "leave room for states to make choices (about) what works for them."

Tester inquired about why the administration isn't requiring the information encoded on the Real ID cards' bar codes to be encrypted. Baker said Homeland Security decided on that approach because police were concerned about an inability to read the information off cards rapidly during traffic stops.

Baker also noted that the machine-readable zone will contain little more than a person's name, address, and date of birth. "That's information that's very hard to hide in an Internet age," he told the committee. "The notion that somehow because it's on a machine readable zone it'll become more available to identity thieves, I think, is pretty speculative."