Scientists discover 15,000-year-old viruses frozen in glacier ice

Most of the viruses were previously unknown to us.

Researchers studying Tibetan glacier ice have discovered a treasure trove of unknown viruses, a find that could bring new insights into how viruses have evolved over time. The team published a paper on the microbes they found, and the methods they used to study them, in the journal Microbiome this week.

"Viruses and bacteria play vital roles both good and bad and thus we need to understand those roles much better. Glacier ice provides one way in which to do that," Ohio State University paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson, who worked on the new study, told CNET in an email.

The glacier samples came from the summit of the Guliya ice cap in western China, 22,000 feet above sea level. Each sample is made up of layers, which act like time capsules, telling a story of past climates and environments.

The research team dated the glacier ice to 15,000 years ago and discovered genetic codes for 33 viruses. Four of those were known to science and at least 28 were novel, or previously unknown. About half the viruses appear to have loved the extreme cold in which they lived, surviving in the harsh environment not despite the frigid temperature "but because of it," Ohio State University said in a statement.

"Our research shows that both bacteria and viruses are archived in the layers of ice making up an ice core so these records should allow us to study such things as the evolution of microbes through time," Thompson told CNET. "Most of the biodiversity on our planet exists as microbes, most of which we know very little about."

The researchers' analysis showed that the "viruses likely originated with soil or plants, not with animals or humans, based on both the environment and the databases of known viruses."

There's precedent for the discovery of long-frozen viruses. Scientists famously revived a giant 30,000-year-old virus found in Siberian permafrost. That virus targeted only amoebas. Thompson said there isn't any evidence at this stage that the frozen viruses described in the new study are capable of being revived.

The paper discusses how glaciers are shrinking due to global warming, a hallmark of human-exacerbated climate change, and says the melting will lead "the loss of those ancient, archived microbes and viruses."

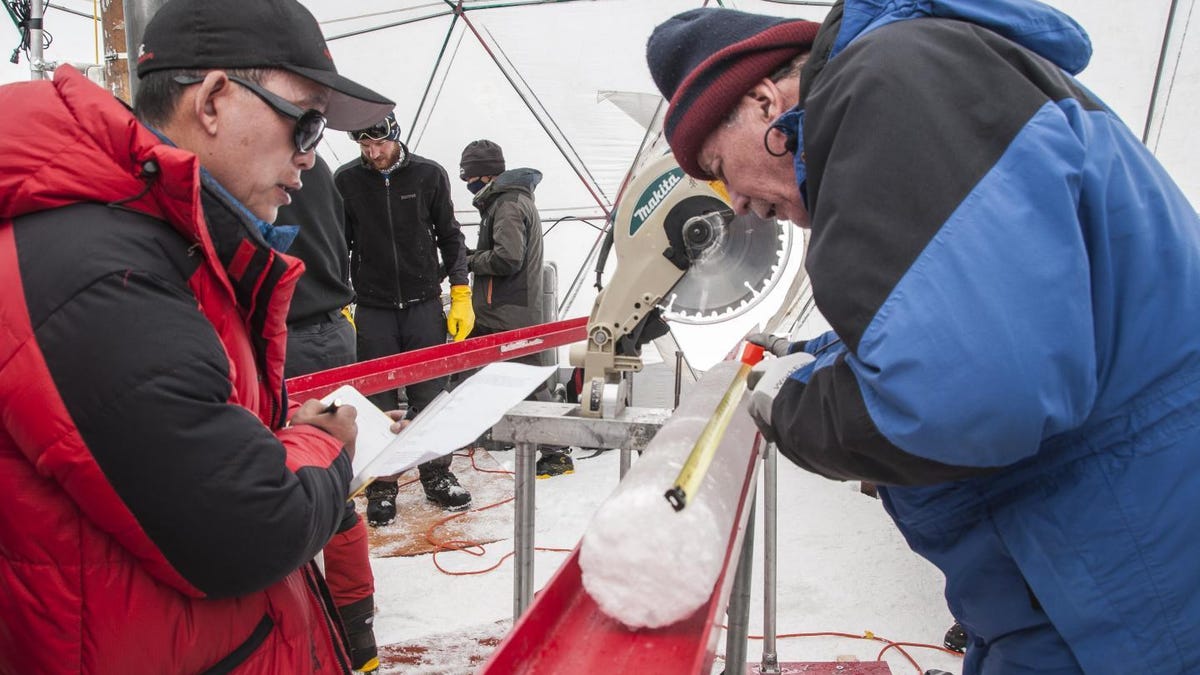

The researchers were able to analyze the ice cores with an "ultra-clean" method that avoided contamination. This process could one day apply to samples from other worlds, like Mars.

The research has left scientists pondering some big, as-yet-unanswered questions.

"We know very little about viruses and microbes in these extreme environments, and what is actually there," said Thompson. "The documentation and understanding of that is extremely important: How do bacteria and viruses respond to climate change? What happens when we go from an ice age to a warm period like we're in now?"