Scientist's $40 microwave zaps better heat-to-power materials

Rensselaer researchers say sulfur-doped and microwave-cooked nanomaterials could lead to refrigerators with no moving parts or cars that make electricity from waste heat.

Researchers think they've found a low-cost machine for producing materials that can convert waste heat into electricity: the microwave oven.

A team from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute last week published a paper in Nature Materials that describes an improved method for making thermoelectric materials. Members of the team have also created a startup company to commercialize the technology.

Thermoelectric devices are already in use today in portable coolers or to heat car seats, either by making electricity from heat or using electric power for cooling. Many scientists and engineers are trying to improve the efficiency of these devices and to bring down their costs, which would open them more applications such as refrigerators with no moving parts or producing electricity from the heat given off by the exhaust pipes on cars or industrial plants.

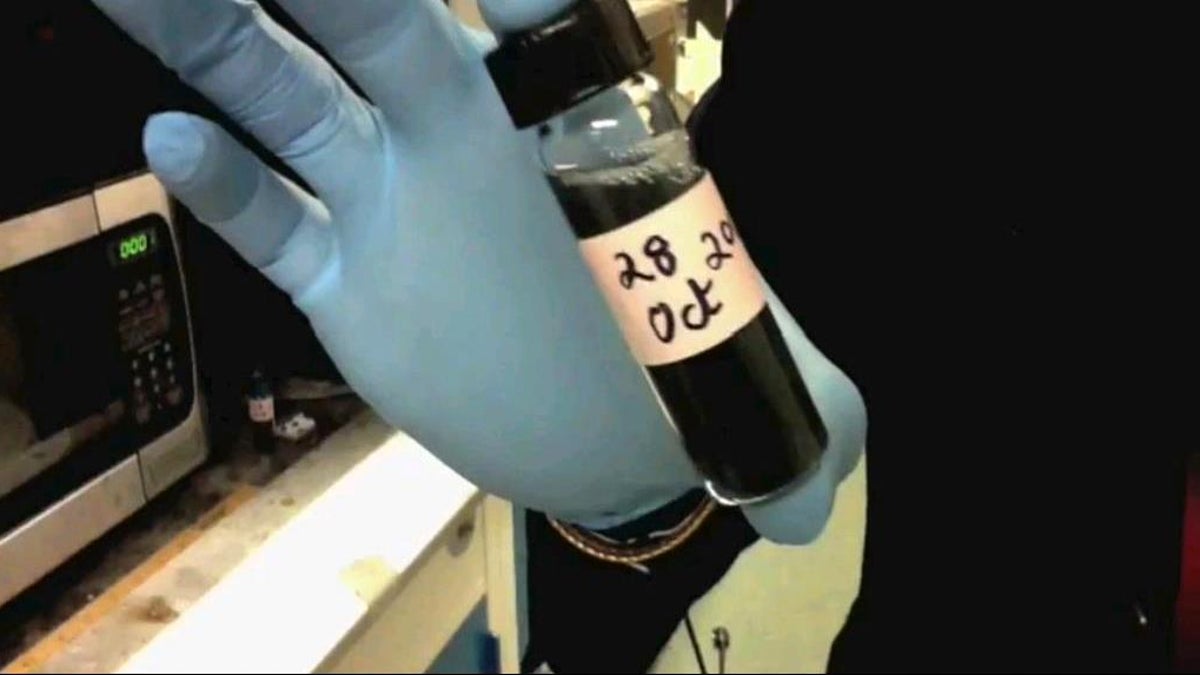

The Rensselaer Polytechnic group used a combination of nanostructuring and doping traditional thermoelectric materials with tiny amounts sulfur. Then in the lab, they used an everyday $40 microwave to heat the material, which brings about a desirable structure and properties in a few minutes.

Using microwaves during production is significant because it means the process could be scaled up at low cost using industrial-scale microwave ovens, said Ganpati Ramanath, a professor at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Rensselaer and co-author of the paper. "We can make gram quantities in less than a minute so that's very good for industrial scale production," he said.

Ramanath and fellow researchers have applied for a patent for their nanomaterial production method and have form a startup company called ThermoAura to commercialize their academic work.

In addition to government sources, such as the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, IBM also had a hand in funding the research. One of the possible applications is to use thermoelectric devices to draw away heat from computers and convert it to electricity.