Scientists unravel mystery of giant cosmic bubble surrounding Earth

The bubble is 1,000 light-years wide and the source of all our star friends.

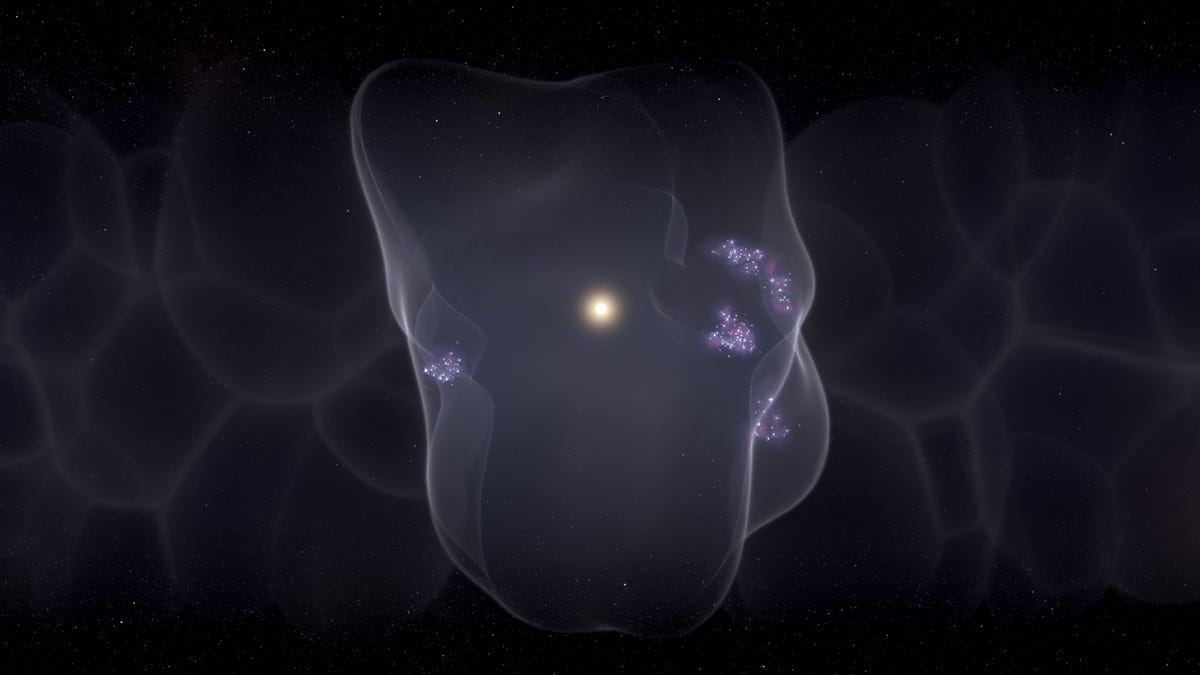

An artist's illustration of the Local Bubble with star formation occurring on the bubble's surface. Scientists say all young stars within 500 light-years of the sun and Earth exist because of this bubble.

Once upon a time in galactic history, a cluster of stars detonated to form fantastical supernovas. The blasts were so strong their sparkly leftovers pushed the surrounding shroud of interstellar gas outward until it drifted into a cosmic bubble 1,000 light-years wide -- a giant blob that's still growing now.

By sheer coincidence, experts say, our very own sun flew directly into this bubble. Now we live smack in the middle of it, earning the globule a fitting name: the Local Bubble. And in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, scientists offer novel details of the bubble's saga using a 3D map of the enormous structure.

Most surprisingly, they found it's the main reason we have an oddly rich neighborhood of young stars.

"This is really an origin story; for the first time we can explain how all nearby star formation began," Catherine Zucker, an astronomer and data visualization expert formerly at Harvard and Smithsonian's Center for Astrophysics and author of the study, said in a statement.

Astronomers typically study seven spots in space where stars seem to form most often -- Zucker's study saw each one sitting right on the surface of the Local Bubble. The team believes that starry bubbles similar to the one encompassing us show up all over the universe, but also that our positioning directly in the center of one is extremely rare.

The concept is comparable with space's fabric resembling a holey Swiss cheese, with each hole representing a star formation center. Somehow, we're in one of the cheesy holes. Because our home star set up shop inside the Local Bubble, every time we peer out at the sky, we're witness to tons of star births.

Beyond that stellar serendipity, the team's awesome 3D animation of the Local Bubble -- which you can play around with here -- sheds light on the structure's evolution.

For instance, the researchers calculated that about 15 supernovas are responsible for the blob's genesis, which occurred approximately 14 million years ago. The sun appeared to have entered the orb about 5 million years ago, and the bubble seems to be coasting along at about 4 miles (6.5 kilometers) per second. "It has lost most of its oomph … and has pretty much plateaued in terms of speed," Zucker said.

Alyssa Goodman, an astronomer at Harvard and Smithsonian's Center for Astrophysics and author of the study, called the team's findings "an incredible detective story, driven by both data and theory." Goodman is also the founder of Glue, the data visualization software that enabled the discovery.

In the future, the researchers hope to continue unlocking the secrets of interstellar bubbles, like the Local Bubble, by applying their software to 3D-map those that lie deeper in the universe.

"We can piece together the history of star formation around us using a wide variety of independent clues: supernova models, stellar motions and exquisite new 3D maps of the material surrounding the Local Bubble," Goodman said.

Zucker wonders, "Where do these bubbles touch? How do they interact with each other? How do superbubbles drive the birth of stars like our sun in the Milky Way?"