You can't hide from government hacking

US law enforcement now has an easier legal path to hack into any computer, anywhere in the world.

The FBI will now find it easier to hack your computer no matter where you are.

Thank -- or blame -- a controversial shift in how judges issue search warrants.

The change, effective Thursday, affects Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which are proposed by the US Department of Justice and approved by the US Supreme Court. It will allow federal investigators to seek permission from a magistrate judge in, say, Texas, to plant hacking software on a computer that's disguising its location.

This form of government hacking is a tool that prosecutors have used to identify suspects in financial crimes and child porn cases, who typically use anonymizing tools to hide their computers' IP addresses. That makes them challenging to catch. The changes will also let investigators use a single warrant to access the computers of hacking victims in some cases.

The Justice Department has called the change essential to fighting crime, but privacy advocates say it gives federal investigators too much power. Some lawmakers also chafed at the lack of public debate on the matter.

On Wednesday, a group of US senators tried to introduce three separate bills that would have either stopped or stalled the rule change. The Senate didn't take up any of the proposed bills, allowing the change to take effect.

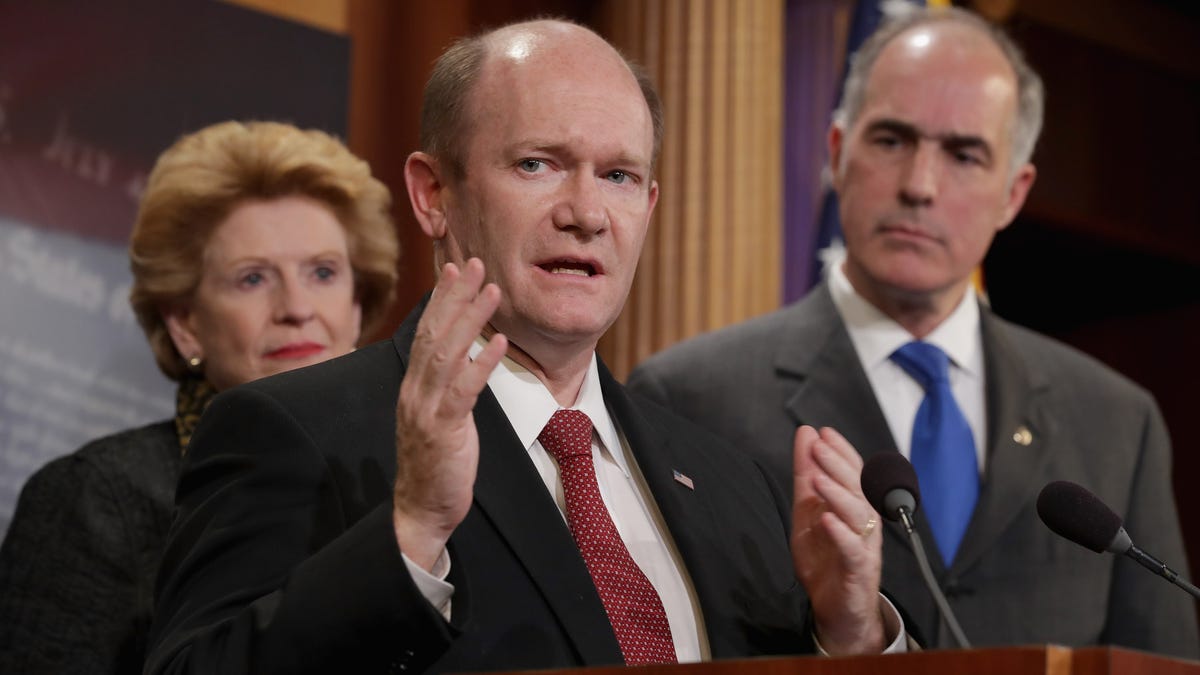

"While the proposed changes are not necessarily bad or good, they are serious, and they present significant privacy concerns that warrant careful consideration and debate," Sen. Christopher Coons, a Democrat from Delaware, said on the Senate floor Wednesday.

A procedural change or a surveillance boost?

Susan Hennessey, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who previously worked as an attorney for the National Security Agency, said the change simply makes it possible for judges to consider these warrants. If there was no judge to consider the warrant, a given search would become impossible, she said.

"It would be really absurd if individuals in the US were able to use technological means to immunize themselves from federal warrants," Hennessey said.

But Andrew Crocker, a staff attorney at the privacy-oriented Electronic Frontier Foundation, said the change is more than procedural.

"Realistically," he said, "a court is going to say, 'This is more authorized than before.'"

Until now, some judges have refused to approve warrants that allow investigators to plant software on computers that could be anywhere -- Oregon, Maryland or Timbuktu. That uncertainty over location has caused these judges to question whether they have the authority to grant the warrant in the first place.

Normally, magistrate judges can allow searches only within their jurisdictions; their authority ends at the border of their judicial district. Now the rules will clearly state they can consider these unique requests from investigators.

Government was already hacking citizens

It's hard to know how long law enforcement agencies have been hacking computers as part of their investigations, and even harder to know exactly what tools they've been using. But they are using them, according to a letter from US Assistant Attorney General Peter Kadzik.

"The use of remote searches is not new, and warrants for remote searches are currently issued under Rule 41," Kadzik wrote earlier this month.

Crocker estimates that the government has been hacking regular people's computers in the US for at least 15 years. But three recent government hacks have prompted public debate over whether the approach is allowed under federal rules -- and under the Constitution.

The first two are investigations of visitors to sites that host child pornography. In one of those cases, investigators used a warrant to plant hacking software on more than 8,000 computers and launched more than 200 investigations based on the evidence they found. All those cases resulted in vastly different decisions from judges about whether, in retrospect, the single warrant was valid.

In a third case, a magistrate judge in the Southern District of Texas refused to grant a warrant in an investigation of financial crimes because law enforcement didn't know where the suspects' computers were.

Government hacking: Not just for bad guys

Government investigators wouldn't just target criminal suspects with hacking software with warrants obtained under Rule 41. The rule changes also let investigators seek a single warrant to hack computers of hacking victims in their efforts to fight a particular kind of online menace: the botnet.

Hackers cobble together networks of hacked computers to carry out nefarious tasks. Increasingly, these attacks are also targeting internet-connected devices we don't always think of as computers, such as security cameras. The rule changes would let government investigators get one warrant to hack all the computers in a botnet and potentially try to disable it.

While that sounds like it could be a good thing, privacy advocates say it's a bridge too far for the government to access victim's computers without their consent or knowledge.

It's also just strange to contemplate, said Jill Bronfman, a privacy law expert at UC Hastings College of the Law. Would some version of Microsoft's much-maligned Clippy appear in your screen, letting you know the government was at work on your computer offering unsolicited help?

"We'll have to think of a good icon for this," Bronfman said.