Ring let police view map of video doorbell installations for over a year

The company once offered a map, now withdrawn, that allowed police to zoom in to see the specific location of Ring customers.

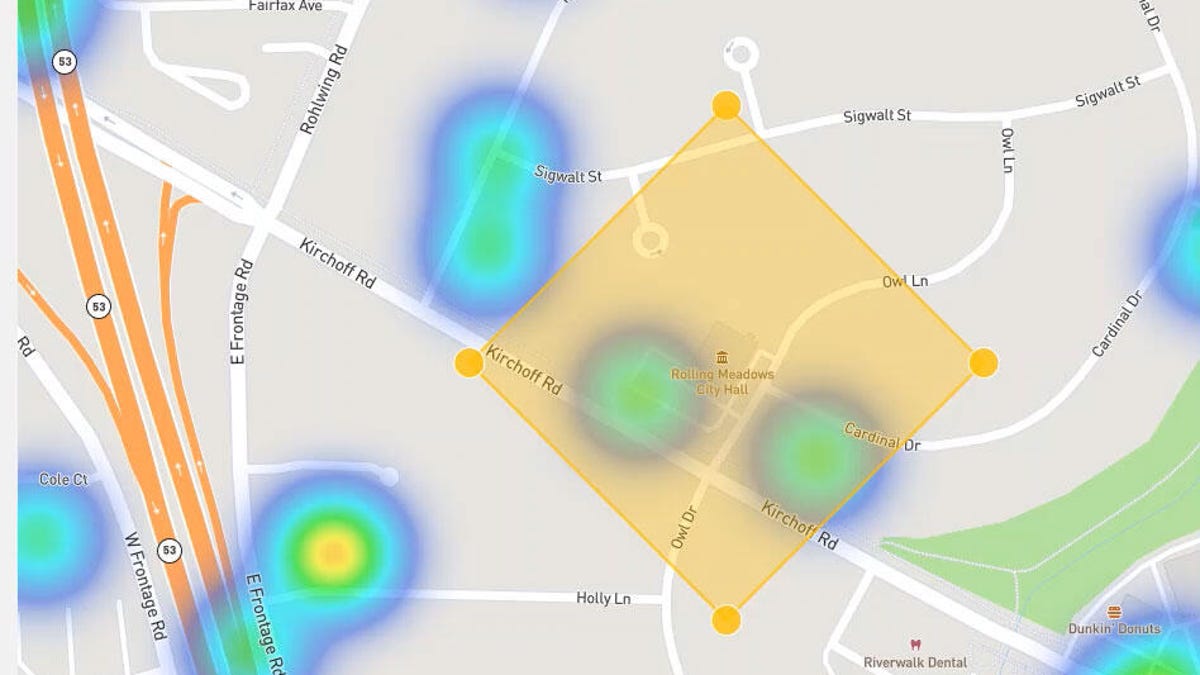

A video obtained from a FOIA request by privacy researcher Shreyas Gandlur showed that police could zoom in on Ring's heat map tool and find specific locations on users.

For more than a year, police departments partnered with Amazon's Ring unit had access to a map showing where its video doorbells were installed, down to the street, public documents revealed. So while Ring said it didn't provide police with addresses for the devices, a feature in the map tool let them get extremely close. The feature was removed in July.

Public documents from the Rolling Meadows Police Department in Illinois, obtained by privacy researcher Shreyas Gandlur and reviewed by CNET, revealed that police had access to a heat map that showed the concentration of Ring cameras in a neighborhood.

In its default state, the heat map showed police where Ring cameras are concentrated: the darker the shade, the more the cameras. But when zoomed in, it would show light circles around individual locations, essentially outing Ring owners to police. Police could also type in specific addresses to see the cameras in the surrounding area.

In a statement, Ring denied that its heat map tool gave exact locations of its users.

"As previously stated, our video request feature does not give police access to the locations of devices. Ring is constantly working to improve our products and services and, earlier this year, we updated the video request process to no longer include any device density information," the company said. "Previous iterations of the video request feature included approximate device density, and locations were obfuscated to protect user privacy. Zooming into areas would not provide actual device locations."

The heat maps feature was one of several surveillance tools that Ring told police "should not be shared with the public." The first Ring police partnership listed started in March 2018, and the video doorbell company had at least 335 police partners by the time it disabled the feature, records show.

Ring, which Amazon purchased for $839 million in February 2018, has now partnered with up to 631 law enforcement agencies in the US, creating a public surveillance tool for police departments through its video doorbells. Ring says the technology can help reduce crime in neighborhoods.

The cameras have helped police solve crimes, including package thefts and the capture of a fugitive, and offers a measure of comfort for homeowners. But advocacy groups and lawmakers have raised concerns about this public-private partnership, citing issues with Ring's close ties to police and the constant surveillance performed by the video doorbells.

A CNET investigation in September found that Ring doesn't limit how police can use the technology. The company admitted this to Sen. Ed Markey, a Democrat from Massachusetts, in letters the lawmaker published in November.

"The more we learn about Ring, the clearer it becomes that this product poses serious privacy and civil liberty threats," Markey said in a statement to CNET after learning about the video. "Information as sensitive as the street you live on should be kept private and secure. There are gaping holes in Ring's privacy policies and the rules governing its partnerships with law enforcement, which Amazon should address immediately."

Zoom insight

When police partner with Ring, they get access to a Law Enforcement Portal, through which they can request footage from residents via its Neighbors app, a network where people can upload clips from their video doorbells.

Police send requests by geofencing part of a map on the portal, and anyone in that area with a Ring camera can choose to send videos to their local police department if they want to participate. The video requests could be narrowed down to 0.025 square miles, about 10 city blocks.

The heat map existed so police could see if there was a concentration of Ring cameras in the areas they were focusing on. But a video showed that police can get a lot more specific in their search.

The video, from February, showed that police could type in an address and the heat map would zoom down to street level and show the location of Ring cameras.

"This revelation demonstrates why Ring's statements about protecting user privacy should not be trusted," said Mohammad Tajsar, a staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. "For months, Ring claimed that its products do not allow police departments to find out who in their neighborhoods own cameras."

Officers are only supposed to get addresses of Ring doorbell owners when the owners choose to send in footage. Ring has consistently told people that police can only get location information this way and that it doesn't provide law enforcement with addresses of Ring owners.

But Ring has given the location of its customers to police before. In August, The Guardian reported that Ring provided a map of its active users in Gwinnett County, Georgia, on request. Gandlur found that Ring sent a similar map to police in Naperville, Illinois. Police in Green Bay, Wisconsin, also kept a log of addresses and contact information on residents to whom it gave Ring cameras from May to June.

Zooming in on the heat map showed that Ring was giving this feature to every partnered police law enforcement agency by default.

"This is yet another example of Ring not being up front about user privacy," Gandlur said. He noted that in February, Ring told The Intercept that user locations were hidden and the company didn't share personal information. "At the same time this was their public messaging, we now know Ring was giving police the locations of all devices with higher specificity than their statements suggest."

The video of the heat map zooming in, obtained by Gandlur, was sent in February to the Rolling Meadows Police Department, days after the agency partnered with Ring. The heat map is intended to show the approximate location of Ring cameras.

But in the video, the demonstration showed the heat map zooming into Rolling Meadows City Hall, turning an orange mass into two specific yellow circles on the block. That information might have been obscured if there were more Ring cameras on the street, but as the video showed, if there are only a few Ring owners on a block, it's much easier for police to spot the locations.

It's unclear how close to the highlighted circles the actual Ring cameras are, but the map essentially showed where on the street they were located.

Rolling Meadows police said they didn't use the heat map feature but acknowledged that the tool could have shown them where Ring cameras were in certain areas. It's unclear how many of the other hundreds of police departments partnered with Ring used this tool while it was active.

"We were originally shown the heat map tool to show us an approximate view of where Ring cameras were located in Rolling Meadows," the department said in a statement. "It never specified exact addresses, only an area of where cameras were located in a specific area in the city."

Knowing where every Ring camera is located in a neighborhood raises the issue of potential police surveillance, said Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, author of The Rise of Big Data Policing and a law professor at the University of the District of Columbia.

"When police can see which houses were likely to have footage, it undercuts the anonymity, or control or consent," he said.

Ring and Amazon promise their video doorbell customers anonymity and privacy from law enforcement, only allowing police to request footage from a geofenced area, not from specific individuals.

In a November letter to Markey, Brian Huseman, Ring's vice president of public policy, acknowledged this was to protect people against being targeted by law enforcement for evidence.

"In particular," Huseman said, "by not providing police any information on who, if anyone, was asked to help with the investigation or if the person opted to not assist, we eliminate the pressure implicit in receiving an in‐person request from police."

Ring now has more than 630 police partnerships across the US. Before the heat map feature was disabled in July, it had at least 330 police partnerships with access to the tool.

By the time Huseman sent the letter, Ring's heat map feature had been disabled for four months. But for more than a year before Ring disabled it, hundreds of police departments could simply zoom in on the map and find individual Ring owners.

With that ability, the "pressure implicit in receiving an in-person request from police" that Huseman mentioned would have been widespread, Ferguson said.

In tweets to concerned citizens, Ring has told people that "police do not have a way to contact users outside of the app." But when police can figure out where Ring owners are from this digital tool, it'd be easy to just find homes and ask for the footage in person.

"It's still in the individual's power to consent," Ferguson said, "but it's very difficult to deal with that level of consent because it's hard to say no to that kind of lawful authority."