Researcher to demo smartphone attack at RSA

Hole in Webkit software used in browsers affects mobile and desktops but is more easily exploited on smartphones where security is limited, researcher says.

A researcher plans to demonstrate an attack on a smartphone at the RSA security conference this week that starts with social engineering via a text message and leads to a malicious Web link that triggers a browser exploit and silently downloads a Trojan.

"It's a demo of a new attack vector on mobile, using a Remote Access Tool" called Nickispy, which showed up a few months ago in China, said Dmitri Alperovitch, formerly of McAfee Labs who is chief technology officer at a brand new startup called CrowdStrike. "No one has publicly demonstrated an end-to-end attack that would deliver an exploit to a phone yet. Malicious apps are a danger, but the greater danger is targeted attacks."

Alperovitch's team reverse engineered Nickispy and also created an exploit for a bug that the team discovered in the Webkit open-source Web browser engine, which is used on mobile and desktop platforms. "We weaponized it on the Android platform for this demo," he said in an interview.

Basically, in the demo scheduled for 10:40 a.m. PT Wednesday, Alperovitch plans to send a targeted SMS message to a planted victim that masquerades as a message from the carrier. The message will warn that the recipient's data plan is about to expire unless the recipient follows a Web link provided to renew service. Once the link is opened in the browser the malware is installed on the device without the victim doing anything else.

An attacker would have to know in advance what operating system the device was running and tailor the message, either SMS or e-mail, to that person to trick them into opening it up and acting on it. This could be particularly dangerous for high-profile targets, such as government officials and CEOs who have a lot to lose if their phone calls and data on their devices were compromised.

Once the malware is on the device, an attacker would be able to receive copies of SMS messages the device sends or receives, record phone calls, activate the microphone and steal data off the phone, according to Alperovitch.

"There is no security mechanism on the phone," Alperovitch said. "There is no app you can buy from any security vendor that's out there that will protect you against this. The fundamental design of the operating system won't give any app administrative access to the device, so you are at the mercy of the OS provider.""They are demonstrating again that mobile devices are like PCs and can be attacked the same way," said Charlie Miller, principal research consultant at Accuvant. "An interesting difference, though, is that mobile devices lack the security software typically seen on desktop computers. Since security software has to behave like other 'apps,' security software on mobile devices can't detect or clean low level malware or attacks. They are constrained by the same restrictions placed on other apps (put there to protect from malware). On PCs, security software run at the lowest level can at least stand a chance against these types of threats. Not so in the mobile space."

Kevin Mahaffey, chief technology officer at mobile security firm Lookout, said the announcement would lead to a "race to patch" to plug the hole.

"In order to fix it, you need a firmware update for the mobile devices," he said. "This will come with a new version of iOS or a new Android firmware update pushed by your operator, which can take weeks or months, or never happen."

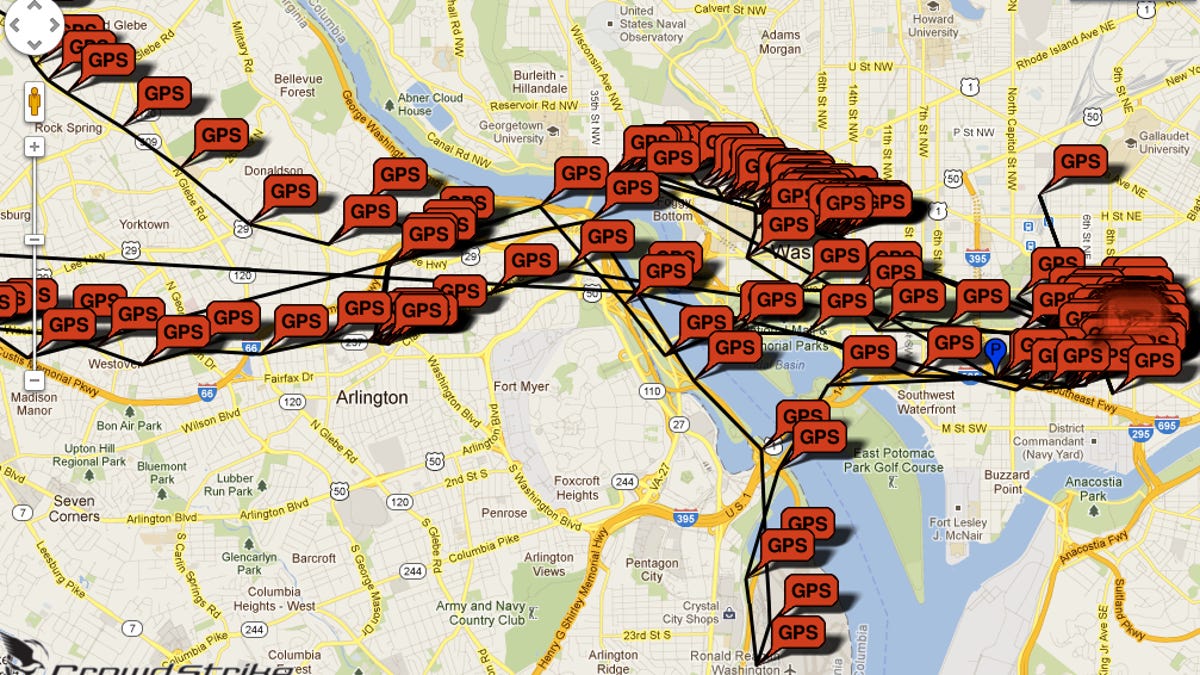

Alperovitch, who revealed details of a huge cyber-espionage campaign this summer dubbed "Shady RAT", announced his new firm--CrowdStrike--last week with George Kurtz, who is president and CEO and who used to be worldwide chief technology officer at McAfee.

The firm has received $26 million Series A funding led by Warburg Pincus. It will focus on using so-called "big data," the seemingly overwhelming amounts of different types of data at companies, to help them protect their most sensitive information.

"It's a technology solution using big data to identify adversaries and their tactics," said Kurtz.

"Humans tend to follow a pattern. That's what we're after, trying to fingerprint their tactics, techniques and procedures and provide that intelligence in real time," Alperovitch added.