'Dayglow' at Rosetta's comet turns out to be unexpected ultraviolet aurora

Years after the Rosetta mission landed on Comet Chury, a new phenomenon has been excavated from its data.

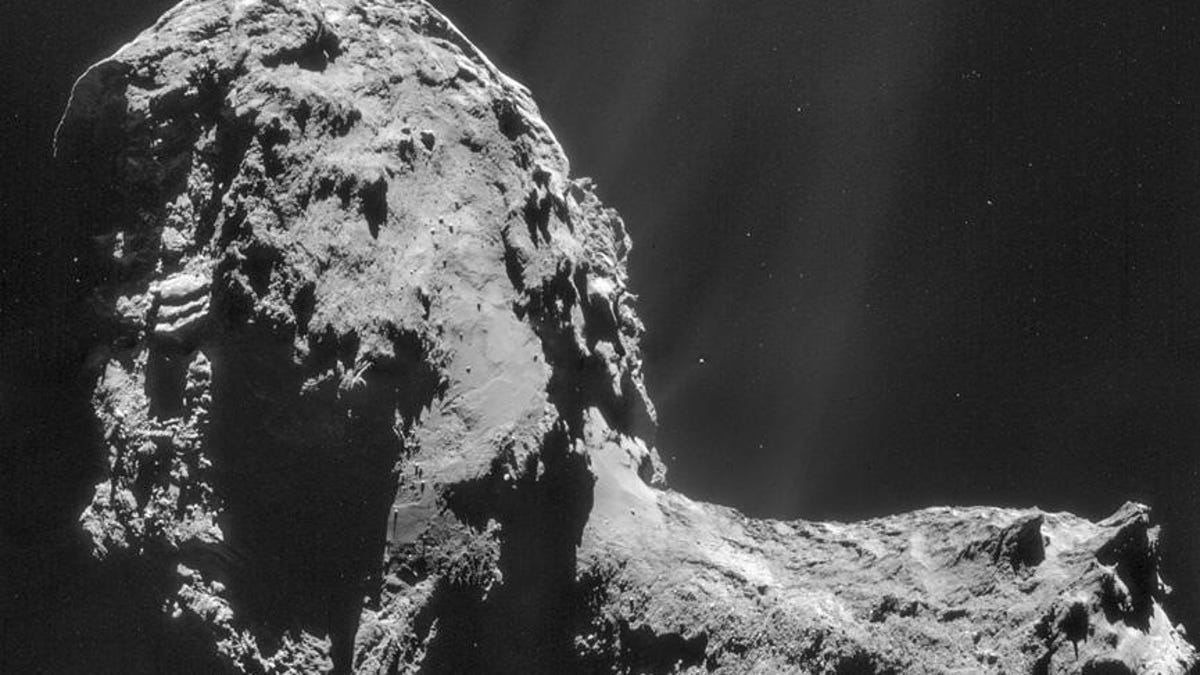

Comet Chury in all its glory

Auroras, better known to we Earthlings as northern or southern lights, aren't limited to planets and moons. For the first time, scientists have identified the same phenomenon at a comet.

The discovery comes courtesy of the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, which famously landed on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, also known as Comet Chury, back in 2014.

On Earth, we get auroras when energetic particles from the solar wind interact with our planet's magnetosphere. When researchers looked at Chury in the far ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum, they were able to pick up a similar effect from solar wind electrons striking the cloud of gas, or coma, around the comet's rocky nucleus.

"The resulting glow is one of a kind," says Marina Galand of Imperial College London, in a statement. "It's caused by a mix of processes, some seen at Jupiter's moons Ganymede and Europa and others at Earth and Mars."

An animation taken from images of comet Chury's rotation and emissions.

Galand is lead author of a paper on the discovery published Monday in Nature Astronomy.

Scientists originally thought that the data showed a "dayglow" -- basically just photons lighting up clouds of gas, which can be easily observed at Earth.

"Since this process is very high energy, the resulting glow is also highly energized and therefore in the ultraviolet range, which is invisible to the human eye," explains co-author Martin Rubin from the University of Bern Physics Institute.

Even though the Rosetta mission ended in 2016, researchers were able to cross-reference data from the spacecraft's different instruments and perform a complicated analysis that led to a new interpretation of what the scientists were seeing.

What's not yet clear is what the lights will be nicknamed. On such a small body, northern or southern lights don't really make sense as a moniker. Perhaps it will just have to be "Chury lights" for now.