Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET The net neutrality battle lives on: What you need to know after the appeals court decision

A federal appeals court has upheld much of the FCC’s net neutrality repeal, but it also said the agency can’t prevent states from adopting their own rules.

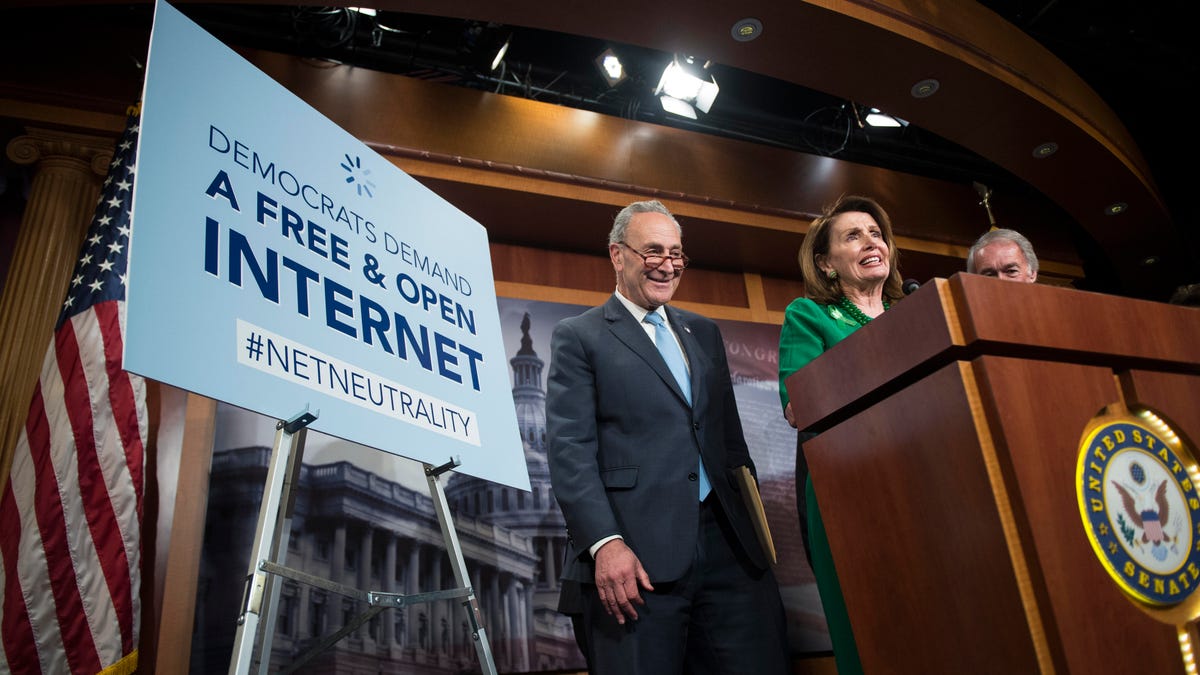

Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi have pushed to pass legislation to restore net neutrality regulations.

The fight over net neutrality doesn't seem to have an end. And such is the case with a federal appeals court decision this week on FCC Chairman Ajit Pai's efforts to roll back Obama-era rules for the open internet. While the court backed the Federal Communications Commission's move, it also opened the door for states to enact their own open internet protections.

The DC Circuit Court of Appeals found the FCC had not overstepped its authority in 2017 when it voted to deregulate broadband companies like Comcast and Verizon. It was an important win for Republicans at the agency. Consumer groups, tech companies and local government officials had sued to restore rules passed in the previous administration.

But there was a wrinkle in the decision: The court also found that the FCC had overstepped its authority when it banned states from enacting their own open internet rules.

Locating local internet providers

Now, the fight to restore net neutrality protections is expected to head to the states.

At stake in this battle is who, if anyone, will police the internet to ensure that broadband companies aren't abusing their power as gatekeepers. The 2015 rules adopted under FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, a Democrat, prevented broadband providers from blocking or slowing access to the internet, or charging for faster access. The rules also firmly established the FCC's authority as the "cop on the beat" when it comes to policing potential broadband abuses.

Locating local internet providers

That all changed when Pai, a Republican, took charge of the agency in 2017. He threw out the old rules and stripped the FCC of its authority. The latest legal battle in Mozilla v. FCC could continue if either side decides to appeal. Congress may also step in to settle the issue. And with a presidential election coming next year and Democrats vowing to restore protections, it's clear the fight is far from over.

If you still don't feel like you understand what all the hubbub is about, have no fear. We've assembled this FAQ to put everything in plain English.

What's net neutrality again?

Net neutrality is the principle that all traffic on the internet should be treated equally, regardless of whether you're checking Facebook, posting pictures to Instagram or streaming movies from Netflix or Amazon. It also means companies like AT&T, which bought Time Warner, or Comcast, which owns NBC Universal, can't favor their own content over a competitor's. That's increasingly important as companies like AT&T push their own services like the upcoming HBO Max offering.

What were the original Obama-era rules?

The regulation prohibited broadband providers from blocking or slowing traffic and banned them from offering so-called fast lanes to companies willing to pay extra to reach consumers more quickly than competitors. It also established a so-called "general conduct rule" that gave the FCC power to step in when it felt ISPs were doing something that hurt competition or ultimately hurt consumers.

What happened to the 2015 rules?

The FCC, led by Pai, voted on Dec. 14, 2017, to repeal the 2015 net neutrality regulations. On June 11, 2018, the rules officially came off the books. As a consequence, today there aren't rules that prevent broadband providers from slowing or blocking your access to the internet. And there's nothing to stop these companies from favoring their own services over a competitor's.

One of the most significant changes that's often overlooked is that the FCC's "Restoring Internet Freedom" order also stripped away the FCC's authority to regulate broadband, handing it to the Federal Trade Commission.

Why did the FCC repeal the 2015 net neutrality rules?

To make sure the rules stood up to court challenges, the agency also put broadband in the same legal classification as the old-style telephone network, which gave the FCC more power to regulate it.

The stricter definition provoked a backlash from Republicans, who said the move was clumsy and blunt. They claim the Democrats' bill to restore the rules will give the FCC too much authority to regulate ISPs.

Pai, appointed by President Donald Trump, called the old rules "heavy handed" and "a mistake." He's also argued the rules deterred innovation because internet service providers had little incentive to improve the broadband network infrastructure. (You can read Pai's op-ed on CNET here.) Pai says he took the FCC back to a "light" regulatory approach, pleasing both Republicans and internet service providers.

Supporters of net neutrality say the internet as we know it may not exist much longer without the protections. Big tech companies, such as Google and Facebook, and internet luminaries, including Tim Berners-Lee, fall in that camp.

Who sued the FCC and why were they suing them?

Attorneys general in 22 states and the District of Columbia joined pro net neutrality consumer groups, like Public Knowledge and Free Press, and Firefox publisher Mozilla in suing the FCC in federal court to reverse the FCC's move.

The US Federal Appeals Court for the DC Circuit in February heard oral arguments in Mozilla v. FCC challenging the FCC's repeal of the 2015 rules. A decision was rendered on Oct. 1, 2019.

Two of the big questions being asked in this lawsuit were whether the FCC had sufficient reason to change the classification of broadband so soon after the 2015 rules were adopted and whether the agency has the right to preempt states, like California, from adopting their own net neutrality laws.

People on both sides of the debate say it's time for Congress to step in and create net neutrality protections.

What was the outcome of that case?

The court upheld the FCC's repeal of the rules, but struck down a key provision that blocked states from passing their own net neutrality protections. It also remanded a piece of the order back to the FCC and told the agency to take into consideration other issues, like the effect that the repeal of protections will have on public safety and the subsidy Lifeline program.

Was this a total victory for the FCC?

The majority of the opinion was in favor of the FCC. On the big question about broadband reclassification, the FCC came out on top.

The court upheld the FCC's authority to classify broadband any way it likes. It's not surprising given that the same federal appeals court two years ago offered a similar judgment in favor of the FCC. In that case, AT&T and others in the broadband industry sued the Democrat-led FCC for classifying broadband as a more strictly regulated "utility" service. Back then the court also deferred to the FCC as the expert agency and said it could classify broadband as it saw fit.

But in Mozilla v. FCC, the court also threw net neutrality supporters a lifeline. On the question of whether the FCC could ban states from passing their own net neutrality laws, the court said the FCC had no authority to do that preemptively.

"The Court concludes that the Commission has not shown legal authority to issue its Preemption Directive, which would have barred states from imposing any rule or requirement that the Commission 'repealed or decided to refrain from imposing' in the Order or that is 'more stringent' than the Order," the opinion reads.

What's this all mean for net neutrality?

The repeal of the federal rules still stands. There are no nationwide rules prohibiting broadband companies from slowing down or blocking access or charging fees for priority access to content.

But states that have passed laws or are considering laws imposing their own net neutrality protections can move forward. Five states -- California, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont and Washington -- have already enacted legislation or adopted resolutions protecting net neutrality. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have introduced bills and resolutions.

If states are now able to decide their own rules, doesn't that make net neutrality even more confusing?

That's exactly the argument the FCC and broadband companies have made. They say that a patchwork of state regulations will make it difficult to deliver service, since broadband by its nature crosses state lines. They say that state laws could have the same chilling effect on investment that they claim the federal regulations have had.

But a senior FCC official told reporters shortly after the court's opinion was made public that the agency believes it still has the right to challenge individual state laws on a case-by-case basis.

What's up with California's net neutrality law?

California passed the most stringent net neutrality regulation last year. The law is based on the 2015 protections, but it goes further. It also outlaws some zero-rating offers, such as AT&T's, which exempts its own streaming services from its wireless customers' data caps. The law also applies the net neutrality rules to so-called "interconnection" deals between network operators, something the FCC's 2015 rules didn't explicitly do.

The Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against California and other states that have passed net neutrality laws. California, and others like Vermont, have agreed not to enforce their laws until the federal litigation is over. The Justice Department has also agreed not to pursue its cases against the states until the litigation has concluded.

Does the appeals court decision end the litigation?

Not necessarily. This case could drag on in a number of ways. Either side in the case has two options when it comes to continuing the legal battle. The first is they could appeal to the US Supreme Court to hear the case based on the parts of the decision that didn't go in their favor. This means the FCC could ask the court to take the case based on the preemption question and Mozilla and the state attorneys general could ask the Supreme Court to hear the case based on the question of FCC authority to reclassify broadband.

The other option is to ask the DC Circuit Court of Appeals for what's called an "en banc" hearing, which will allow the full panel of justices to hear the case. Previously, the case was heard by a panel of three judges.

Either scenario is risky for the parties seeking further review. For instance, the US Supreme Court takes very few cases each term. And there's a good chance the high court wouldn't want this case even if an appeal is filed. Also, asking for an en banc hearing has its own risks. Because each side "won" something in this decision, the parties risk losing it all if they ask the full panel to review the case or even if the Supreme Court takes the case.

At this point, it's unclear whether the litigation will continue.

What's it all mean for me?

The 2015 net neutrality rules officially came off the books in June 2018. People on either side of the debate say there have already been real consequences. Pai has argued there have been positive effects, such as an increase in broadband investment. Net neutrality proponents dispute this claim.

Meanwhile, net neutrality supporters say there have been several negative consequences resulting from the repeal. For example, they point to a study from Northeastern University and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst published earlier this year that found that AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon have all artificially slowed down online videos from services like Netflix and YouTube.

They also point to Verizon's throttling of the Santa Clara County Fire Department's service, which affected the agency's ability to provide emergency services during California wildfires. The fire department experienced slowed-down speeds on their devices and had to sign up for a new, more expensive plan before speeds were restored. While Verizon said the incident was due to a mistake on its part, the fact that the FCC no longer has authority over broadband service left the Santa Clara County officials with no agency to lodge a complaint.

Still, most Americans would say they have seen very little change in their broadband service since the repeal took effect. And it's likely the same will be true following the outcome of this latest chapter in the net neutrality saga.

Over time, though, they could. Whether you think the changes will be for the better or worse depends on who you believe.

Is there a chance that net neutrality rules could be restored?

Yes. As we enter the 2020 presidential election year, several Democrats seeking the nomination for president have already said they would appoint FCC commissioners who would restore net neutrality. If Democrats regain control of the White House, the FCC will most likely reinstate rules.

How can the back and forth on this issue be stopped?

The majority of Americans agree that some kind of net neutrality protections are a good idea. They also agree it's not good public policy to allow this issue to continue to ping-pong at the FCC based on which party is in control.

The only way to stop that is to have Congress pass legislation.

But that's where the agreement ends. Democrats in the House have already passed the Save the Internet Act, which would essentially reinstate the 2015 order and once again make the FCC the agency in charge of policing broadband. But Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has blocked it from a vote.

Republicans oppose the bill, saying they're still worried the FCC will have too much control over the internet. And they're pushing for a bipartisan compromise.

While it's clear the bill would have an uphill battle in the Senate, which is controlled by Republicans, Democrats were able to pass a Congressional Review Act resolution in the Senate last year that would've repealed the FCC's order to dismantle the 2015 rules. But it's unlikely any Republicans will defect again to pass this legislation, even if Democrats succeed in getting it to the floor of the Senate.

If it passes both houses of Congress, it still has to be signed into law by Trump. And White House advisers have already said they are advising the president to veto it.

This story was originally published on April 23, 2018. It has been repeatedly updated, most recently on Oct. 3, 2019.