NASA's Voyager 1 detects faint, monotone hum beyond our solar system

Beyond the boundaries of our solar system, a gentle rain of plasma falls.

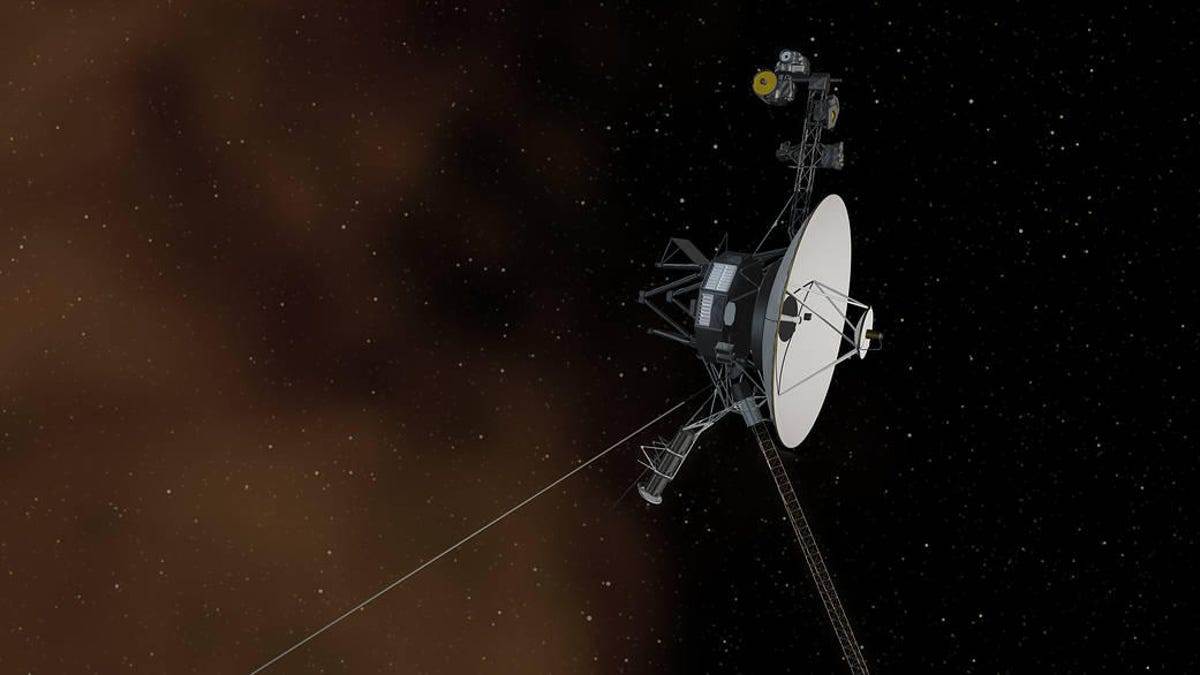

This artist's depiction imagines what Voyager 1 looked like when crossing into interstellar space.

NASA's Voyager 1, the farthest spacecraft from Earth, said farewell to the solar system almost a decade ago, passing through an invisible door some 11 billion miles from Earth and crossing into interstellar space . Since then, it's tacked on another 3 billion miles and it's still sending home data, allowing scientists to probe the space between stars. In a paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy on Monday, researchers examined data beamed back by Voyager 1's Plasma Wave System over its journey, but particularly after it passed through over the solar system's border.

The border is a messy "edge" where the sun's influence disappears and the interstellar medium begins. The medium is typically characterized as empty, desolate and dark, but the PWS on Voyager 1 has detected a low, constant pattering against its detector, space raindrops gently falling on a window. Those drops signify plasma waves -- or interstellar gas -- is constant company for the spacecraft.

"We're detecting the faint, persistent hum of interstellar gas," said Stella Koch Ocker, a doctoral student at Cornell University who led the research. "It's very faint and monotone, because it is in a narrow frequency bandwidth."

For almost one billion miles, Voyager 1 could hear the monotone drone and the researchers believe these weak plasma waves are distinct from other detections made in the vast nothingness of interstellar space. For instance, sometimes the sun gets cranky and erupts, spitting particles out into space. The outbursts have a characteristic signature that James Cordes, an astronomer at Cornell, likens to a lightning burst.

Those bursts were once used to determine the density of interstellar plasma, but this low, constant hum shows Voyager is collecting plenty of information without the solar outbursts. "Now we know we don't need a fortuitous event related to the sun to measure interstellar plasma," said Shami Chatterjee, a research scientist at Cornell and co-author on the paper.

Future missions to interstellar space would help clarify what's happening out there -- and NASA has plans for such a mission, feasibly, in the 2030s.

Voyager 1 has a sister probe, Voyager 2, which is travelling out of the solar system in a different direction. In 2020, while upgrades were being made to one of the Deep Space Network's communications dishes, Voyager II wandered space alone. In November, we pinged the spacecraft for the first time in eight months and, fortunately, it pinged back a "hello."

The pair were launched in August and September 1977 and have been zipping away from Earth ever since. Voyager 2 left the solar system in 2018 at a completely different point to Voyager 1. The crossing enabled researchers to further probe the heliosphere, the giant, protective bubble of solar wind that encapsulates the solar system.

Follow CNET's 2021 Space Calendar to stay up to date with all the latest space news this year. You can even add it to your own Google Calendar .