NASA unveils lunar image recovery project

Called the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project, the initiative is designed to take thousands of 1960s-era analog images and convert them into digital ones.

MOFFETT FIELD, Calif.--Scientists who want to see how the moon has changed in the years since the Apollo missions will soon have the ability to do just that.

That's thanks to a new NASA project in which the agency has restored 42-year-old images taken of and from the moon, all of which will be made freely available to the public.

And while many people will surely have an interest in examining the iconic images, several NASA personnel on hand Thursday at an event celebrating the project explained that it provides the real scientific benefit of making it possible to closely compare even the smallest changes to the lunar surface over the last 40-plus years.

The images in question were taken in the 1960s by cameras onboard five separate Lunar Orbiter spacecraft. They were captured on magnetic tapes and then transferred to film for analysis.

Unfortunately, the full resolution of those images was not available because the technology didn't exist to extract it all.

And in the years since, the data has been stored on large tapes, awaiting the eventual decision of what to do about them.

Now, the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP), which is based at NASA Ames Research Center here, has undertaken the task of translating the original analog data from 1,500 tapes taken from the Lunar Orbiter spacecraft and stored at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory into digital form from which the highest resolution can finally be analyzed.

"This project is an opportunity to revel in what was done in the past," said Pete Worden, director of Ames Research Center, "and get excited about what we're doing in the future."

In particular, Worden said, because once NASA returns to the moon in the coming years, scientists looking closely at the high-resolution versions of the images will be able to see in minute detail how things on the lunar surface have changed.

Once the translation of the images is finished, NASA plans to make all of them available to the public in digital form with the idea that they will be viewable for generations to come.

Worden said that one benefit of being able to compare the historical images with new ones that will be taken starting next spring from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is that it will be possible to see recent meteor impacts too small to see in images taken from afar.

And that's because these images are the highest-resolution taken of the lunar surface to date, said Dennis Wingo, who led the image recovery process.

Greg Schmidt, deputy director of NASA's recently opened Lunar Science Institute, said: "Just imagine for a moment taking these images here, and the hundreds more (that will be generated by LOIRP) and comparing them with what the lunar reconnaissance orbiter will be returning to us in the coming years. We're going to see how the moon is changing, and I'm expecting some very interesting surprises."

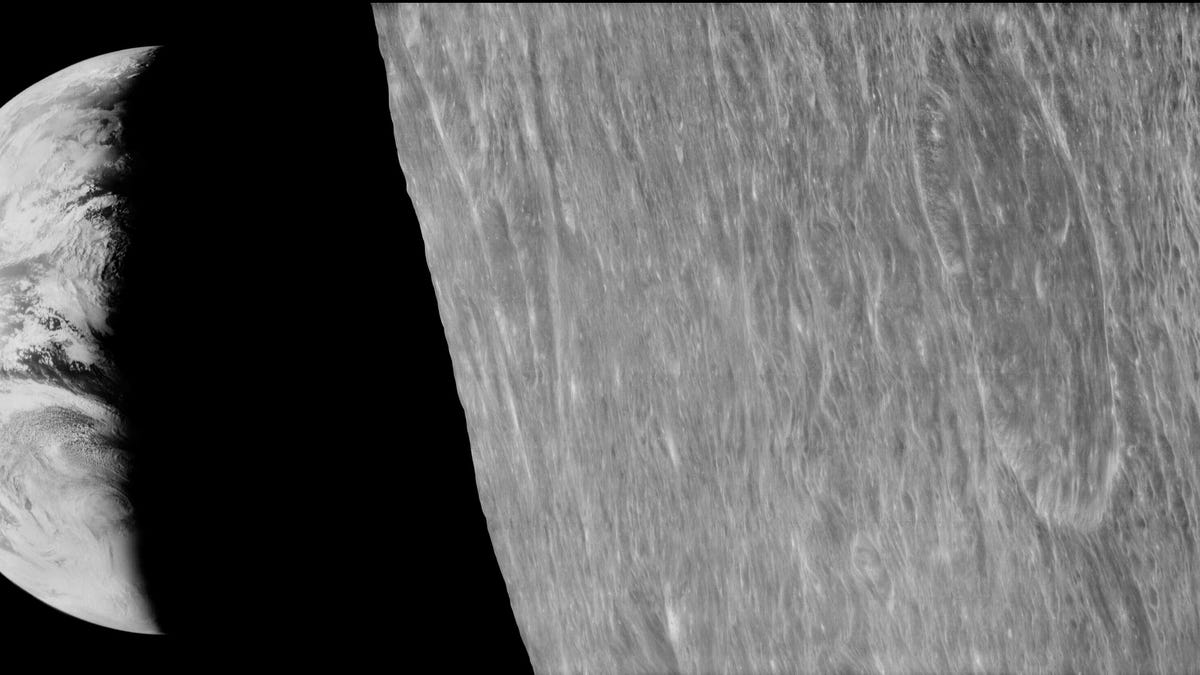

The image shown above, the "image of the century," was the first ever taken in which Earth is seen from another celestial body. In it, it is possible to see the north coast of Africa, as well as the glint of the sun on the Atlantic Ocean, said Wingo.

That glint is important, Wingo said, because it indicates to astronomers the possibility of other Earth-style planets.

Wingo also explained how he and his team worked frame by frame to extract the original analog information and turn it into the currently available digital images (See video below).

All told, Wingo said his team has 48,000 pounds of tape to deal with, and that the time frame to complete the project is very short as there is only one person on Earth who has the expertise to work with the playback heads needed to process the original tapes. And at 68 years old, he wants to retire in just 14 months.

"We're almost at the closing of the window," Wingo said. "If we hadn't done this now, it wouldn't have been possible."