Moon's magma ocean was likely bombarded by asteroids, scientists say

Even when it was still relatively fresh out of the cosmic oven, our satellite got heavily impacted.

The moon has been beaten up quite a bit over billions of years.

Our poor moon has been something of a punching bag for the inner solar system, and new research shows it's likely been getting pounded since it was still a warm, soft little baby planetoid.

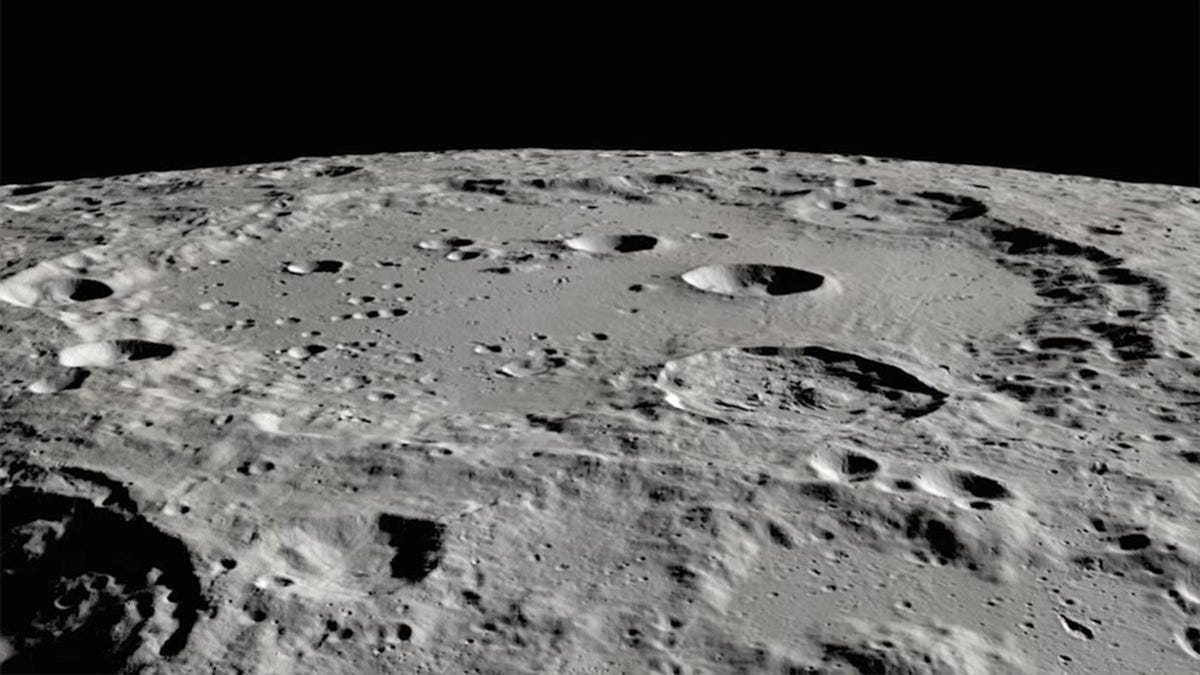

Without any atmosphere to protect it, the moon has taken a lot of licks from asteroids and other wayward celestial objects over the eons, as the many craters on its surface testify. But a new study out of Australia's Curtin University suggests some primordial impacts may be responsible for shaping some of the moon's larger features.

"These large impact craters, often referred to as impact basins, formed during the lunar magma ocean solidification more than 4 billion years ago, should have produced different-looking craters, in comparison to those formed later in geologic history," Curtin professor and lead researcher Katarina Miljkovic explained in a statement.

The study appears in the journal Nature Communications. Milijkovic says it could explain the origins of basins like the lunar South Pole-Aitken basin that are less defined and ring-shaped than younger impact craters.

"A very young moon had formed with a global magma ocean that cooled over millions of years, to form the moon we see today," Milijkovic said. "So when asteroids and other bodies hit a softer surface, it wouldn't have left such severe imprints, meaning there would be little geologic or geophysical evidence that impact had occurred."

As the moon aged and cooled, its surface hardened, and the imprints left by being bombarded would form the more distinct craters we can more easily make out today.

Miljkovic says the research helps fill in some of the gaps in our understanding, and not just of the moon's history.

"This finding will help future research understand the impact that the early Earth could have experienced and how it would have affected our planet's evolution."