Scientists say Mars may simply be too small to host life

The red planet just wasn't big enough to get a grip on its water, new research concludes.

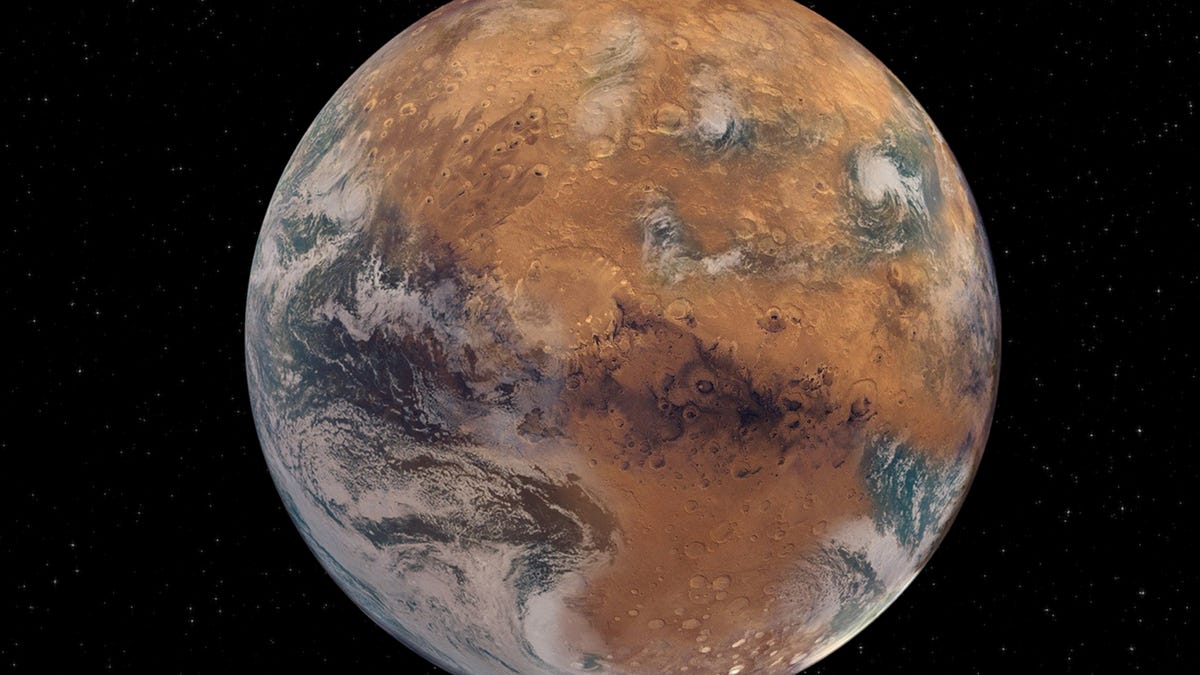

This artist's rendering shows how a more Earth-like Mars might appear with water on its surface.

Plenty of data from Mars suggests the nearby red world was once much more watery, like Earth. Today, of course, there appears to be no liquid water on the planet's surface, and scientists have suggested several possible explanations for the famed Martian aridity.

It's possible a period of volcanic activity shifted the climate, some say, while another popular theory blames Mars' lack of a strong magnetic field for allowing its atmosphere -- and eventually all of its water -- to simply drift out into space. A new study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences puts forward a more basic reason for the planet's persistent thirstiness: It's just too small.

"Mars' fate was decided from the beginning," Washington University planetary sciences professor Kun Wang, a senior author of the study, said in a statement. "There is likely a threshold on the size requirements of rocky planets to retain enough water to enable habitability and plate tectonics, with mass exceeding that of Mars."

Wang and colleagues studied the amount of potassium isotopes present in Martian meteorites, using the element as a sort of tracer for more volatile molecules, including water. The researchers found that during its formation, Mars lost more water and other volatiles than its larger neighbor Earth, while retaining more life-supporting molecules than smaller, drier bodies like the moon or the asteroid Vesta do.

"This study emphasizes that there is a very limited size range for planets to have just enough but not too much water to develop a habitable surface environment," said study co-author Klaus Mezger from Switzerland's Center for Space and Habitability at the University of Bern. "These results will guide astronomers in their search for habitable exoplanets in other solar systems."

This could mean that as we continue to search the skies for an answer to the critical question of whether we're alone, it might be wise to start skipping some of the more puny planets in the galaxy. Good news is that those were going to be harder to spot anyhow. Super-Earths here we come.