Mars hides an ancient ocean beneath its surface

New NASA-backed research finds a surprising amount of water locked away in the red planet.

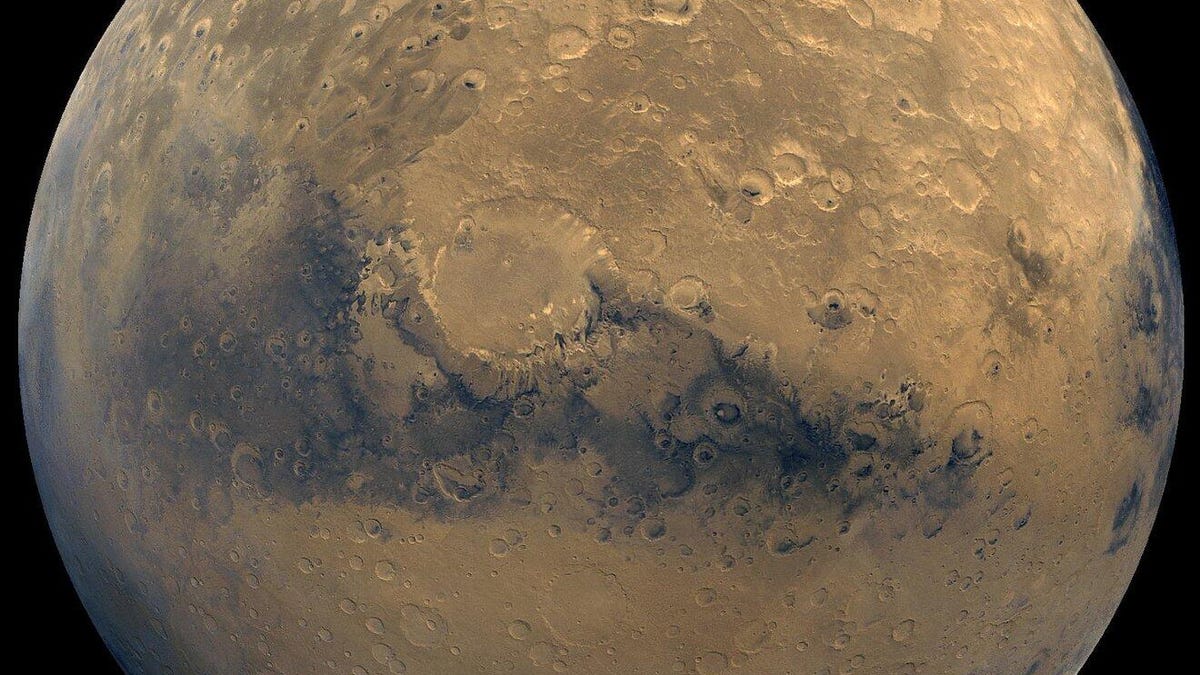

This global view of Mars is composed of about 100 Viking Orbiter images.

For decades, scientists have speculated about what may have happened to all the water on Mars, which is believed to have been a substantially wetter planet eons ago. Some water can be found frozen in the Martian polar ice caps, but new research indicates there's also a shocking amount of water in Mars. The discovery could have a major impact on developing plans to harvest water for a future human presence on the red planet.

It's been largely presumed that as Mars' ancient atmosphere was gradually sucked out into space, much of its surface water went with it. But a new NASA-backed study suggests a significant portion of all that Martian moisture is still on the planet, trapped in its crust.

"Atmospheric escape doesn't fully explain the data that we have for how much water actually once existed on Mars," Caltech Ph.D. candidate Eva Scheller said in a statement. Scheller is lead author of the study published Tuesday in the journal Science.

Scheller and colleagues looked at models that quantify the amount of water on Mars over time in different forms as well as current data on the chemical composition of the Martian atmosphere and the planet's crust. They found that the atmospheric escape theory could not completely account for conditions seen today above and below the surface of our neighboring world.

"Atmospheric escape clearly had a role in water loss, but findings from the last decade of Mars missions have pointed to the fact that there was this huge reservoir of ancient hydrated minerals whose formation certainly decreased water availability over time," explains Bethany Ehlmann, CalTech professor of planetary science.

When water and rock interact, a chemical weathering process can occur that creates materials such as clays that contain water within their mineral structure. This process happens on Earth, but the geological cycle eventually sends moisture trapped in rocks back into the atmosphere via volcanism. Mars, however, appears to have very little if any volcanic activity, leaving all that water stuck in the crust.

"All of this water was sequestered fairly early on, and then never cycled back out," Scheller says.

The team found that 4 billion years ago, Mars had enough water to cover the entire planet with an ocean between 100 and 1,500 meters (328 and 4,920 feet) deep, and that between 30% and 99% of that water is now trapped in minerals in the crust.

Scheller and Ehlmann will aid the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover team in collecting rock samples from Mars for eventual return and study here on Earth to test the theory.

Follow CNET's 2021 Space Calendar to stay up to date with all the latest space news this year. You can even add it to your own Google Calendar.