Man builds model human colon, studies what comes out

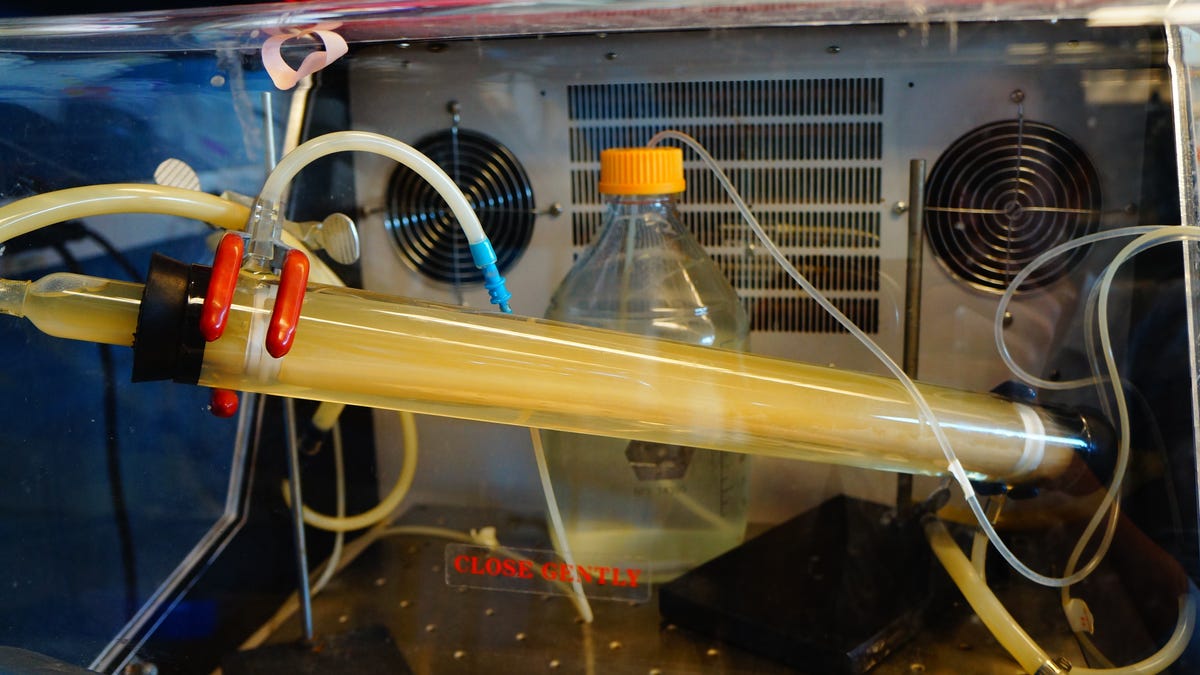

In order to follow the life cycle of bacteria, an engineer builds a model human colon and feeds it three times a day for weeks.

Science stinks, literally. At least it does when you build a model human colon to follow the life cycle of E. coli and other bacteria.

After noting that scientists tend to study bacteria in isolated environments with carefully crafted growing conditions, engineer Ian Marcus, who recently earned his PhD from UC Riverside, decided to take matters into his own hands.

He built a system that models a human colon, a septic tank, and groundwater; fed the colon three times a day for weeks; let the bacteria grow alongside other microorganisms such as protozoa and fungi; and took copious notes.

What he found is a little unsettling: E. coli immersed in microbial communities such as those found in his model colon are less mobile in aquatic environments and thus more prone to biofilm (a sort of microorganism refuge) than strains found in more isolated environments. In other words, the E. coli has a longer shelf life than previously thought, thereby traveling further in groundwater than we'd like to think.

"This means that pathogens could potentially linger longer and over a long period of time travel greater distances in the groundwater," said Marcus in a school news release.

Marcus, who claims to be the first to simulate an environment where the life cycle of bacteria such as E. coli can be observed from the human colon all the way to water treatment and then on to groundwater, adds that his work has been turning some hesitant heads. "People would give a kind-of-interested-but-definitely-don't-talk-about-it-during-dinner look because we're literally dealing with crap," Marcus said. "It has got the smell. It has got everything."

Marcus' findings appear in the journal Applied Environmental Microbiology alongside coauthors that include his former classmates and lab head Sharon Walker.

Only time will tell what can be done with this information, but Marcus has certainly shown that it is best to simulate real environments as closely as possible, especially when studying pesky little microorganisms that are prone to change drastically even when conditions are only changed slightly.