How Mark Zuckerberg inspired a more social Bing

The story behind the latest iteration of Microsoft's search engine includes guidance from Facebook's CEO as well as Bill Gates, as the two companies step up their battle with Google.

Ten developers from Microsoft flew into San Francisco in late February last year to bang away on code with ten counterparts from Facebook.

This hackathon, something the two partners do with some regularity, had a special guest as the day wore on: Facebook co-founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg. In one of the dozens of generic conference room that dot Microsoft's Mountain View campus, the crew spent hours swapping ideas and sharing code, coming up with new ways to integrate Facebook's social network into Bing's search technology. Near the end of the day, Zuckerberg talked to the assembled coders.

"Zuck said, 'Don't try to do social by building social on the side. Build it into the experience,'" Microsoft corporate vice president of search program management Derrick Connell recalled.

It wasn't some grand pronouncement. It was something Zuckerberg kept coming back to as he shared details about Open Graph, new technology that Facebook would introduce in the coming months to allow partners to tap into the social network for their own services.

"He said it four or five times," Connell said. "It was a clue."

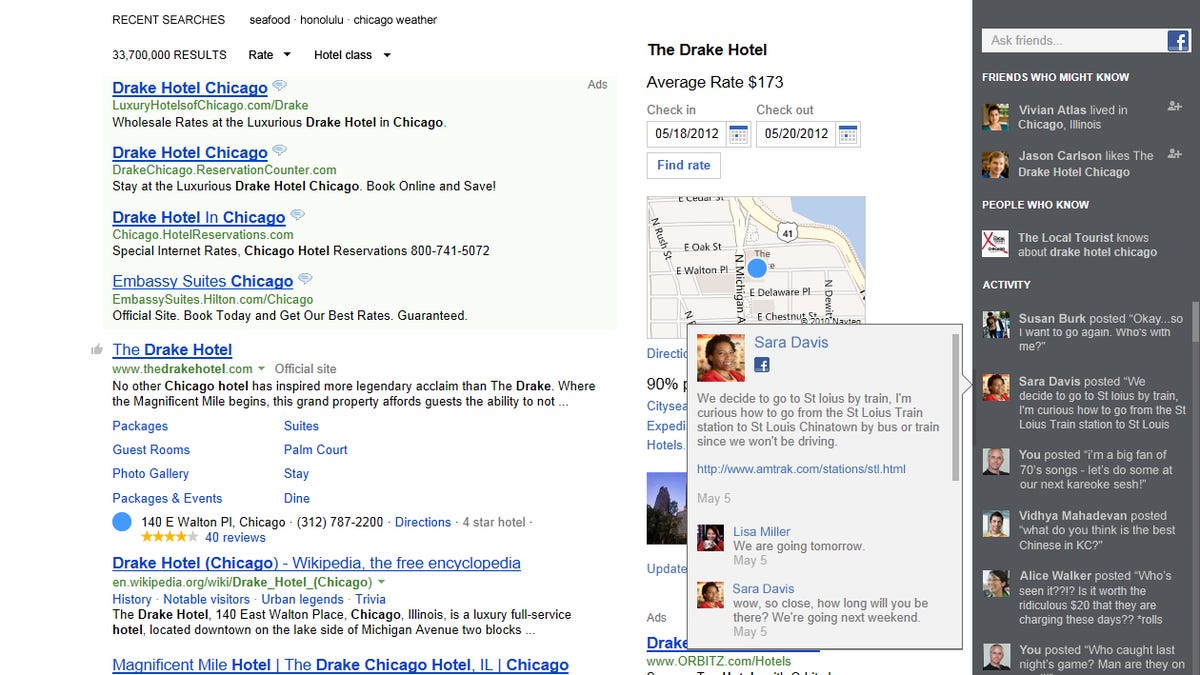

The seeds planted by that clue came to life today as Microsoft introduced a new version of its Bing search engine. The folks at Microsoft have cleaned up the search results page. They've removed some of the shading at the top of the page. But the big change is a new gray sidebar on the right side of the page featuring a separate set of search results culled from the searcher's specific Facebook friends.

The idea is to give searchers the opportunity to query friends who might be able to offer expertise on specific topics, such as a great Thai restaurant in San Francisco or a cheap, clean hotel in midtown Manhattan. Traditional searches on those topics yield links that may help. But often, the information comes from sources users don't know whether to trust.

When users sign into Facebook, those familiar 10 blue links are still there. But Bing's new sidebar connects searchers to friends that may have specific insight into their queries. If those friends have "liked" a Thai restaurant in Noe Valley or they posted photos from a recent trip to New York, they'll pop up in related searches in the sidebar under the heading "Friends Who Might Know."

Below that, in the same column, are links to "People Who Know," enthusiasts on specific topics culled from services such as Twitter and even Google+, who they can follow. At the bottom of the column is "Activity," featuring the latest updates to the user's Facebook News Feed.

The key category, though, is "Friends Who Might Know." When users of the new Bing hover over the name of a Facebook friend, a widget pops open showing the related links on Facebook from those friends. And users can ask those friends for guidance through Facebook directly from the Bing page. That way, they can delve deeper to get information they need to make decisions.

"People are as important as pages," said Adam Sohn, general manager at Bing. "People have become first-class entities in search and it's not trivial."

Perhaps most important, Bing is offering a feature archrival Google can't. Because of Microsoft's partnership with Facebook, it can tap into the social network's 900 million users to make search results more relevant. Google, of course, recognizes the importance of social networks in search as well, which is why it launched Google+. But the service has, by Google's account, 170 million users, a fraction of those on Facebook. And many of them don't appear to be as engaged as people on Facebook.

That's key to giving Microsoft any hope of clawing its way into Google's seemingly insurmountable lead. Google holds 66 percent share of the U.S. search market, compared to Bing's 15 percent share, according to ComScore. Microsoft can point to data that shows that Web searchers, in blind tests, find Bing's results every bit as good as Google's. But Web surfers show no signs of fleeing Google.

"Being as good as the other guy is not enough," Connell said. Bing has to give Web surfers a reason to switch.

That's the job Connell was tasked with Sept. 15 when Qi Lu, the president of Microsoft's Online Services division, promoted Connell from partner group program manager on the Bing User Experience team to help guide the remake the search engine. Connell had just returned from a vacation in Italy when Lu summoned him to a meeting in his Bellevue, Wash., office. Lu tasked Connell with one mission: answer the question, "Why Bing?"

"I came away from the meeting with the understanding if I couldn't answer the question, 'Why Bing?' I wouldn't be in the job for very long," Connell said.

It took Connell and his colleagues some time to realize it, but the answer lay in the talk Zuckerberg gave seven months earlier. Bing needed to bake social networking into the search experience, not merely tack on some features that used data from Facebook. And they got an important nudge in that direction from one of their semiannual meetings with Microsoft chairman Bill Gates.

"He was probably the first person who said your friends are more likely to help you figure out things, rather than experts," Connell said.

Bing needed to come up with a way to replicate asking friends for guidance in search in the same way they do it on Facebook. The challenge was finding the right friends for each query because people rarely write down everything they know about topics in which they have knowledge.

"It's all in their heads," Connell said. "If you ask me about snowboards, I can go on for hours. But I'll never write it down."

The Facebook partnership, though, offered Microsoft a way to find those connections. That's because Facebook users frequently "like" businesses that cater to their special interests. They often post photos of themselves doing things in which they have some expertise. So the Bing team set about indexing all the data generated on Facebook, then built a search engine capable of mapping that information to each user's social graph.

At an all-hands meeting on Dec. 2 for the 2,000-person Bing team at the Meydenbauer Center, a convention hall just around the block from Bing's Bellevue office, Connell and his colleague Harry Shum, corporate vice president of core search development, peddled the new Bing to Lu as though he was a venture capitalist. The duo scripted their pitch. But Lu, who knew the general direction the group was taking, ad libbed his response.

Lu told the pair that he'd support the shift only if they committed to producing high-quality software design, to delivering finished bits by May 1, and to "working everyday from now until your done," Connell recalled.

The result debuts today. Will it dent Google's massive lead in search? Rebecca Lieb, an analyst at Altimeter Group, likes the new interface. And she's impressed by the effort of combing Facebook for signals that could help searchers find more answers to their queries.

But Lieb isn't convinced that users will flock to the new service. It's unclear if searchers will find utility in the ability to connect to their friends right from search.

"Whether there is enough benefit in this remains to be seen," Lieb said.

There's no doubt the service could still use some refinement. A search for Seattle happy hours proffers friends who live in Seattle regardless of whether they've "liked" a particular bar. The idea is that someone from Seattle might have an idea of a fun joint. But for a Seattleite with several Facebook friends from the city, the results are random. Some of those friends may enjoy hitting the bars while others could be teetotalers.

What's more, Microsoft isn't indexing posts that people write on their Facebook walls because those are private by default. It will only cull "likes" and tags from photos, if they've been made public. So if a Facebook user waxes on about a terrific Italian dinner but doesn't click on the thumbs-up "like" button on the restaurant's Facebook page or post a photo from the meal, the person won't necessarily show up in the "Friends Who Might Know" results.

Connell said his team will continue to tune the algorithm. Their work hasn't ended. But, Connell said, the team has begun to give users an answer to the question, Why Bing? It's because the search engine is providing them answers they can't get elsewhere.

Updated at 10:47 a.m. PT to clarify that users will only need to sign into Facebook and not Microsoft's Windows Live to access the new service.