How an eye-tracker can make Google Glass less creepy (Q&A)

A Google Glass developer with a clear vision of what Glass can be, Brandyn White sees how Glass can be a force for good with a feature that Glass doesn't even have yet.

Brandyn White's adventures hacking on Google Glass began not in a fancy Silicon Valley lab, but in a St. Petersburg, Fla., car repair shop in the mid-1990s.

His dad gave him a Tandy personal computer. The classic DOS desktop tower, "which was old then," White said with a laugh, was part of a payment his dad had received for fixing a customer's car. Limited in what he could do with the Tandy, White soon picked up a programming book from his school library. He was 10.

By the time he was a teenager, White had started a company called ConnerSoftware, which involved him "knocking off" -- his words -- other software and giving it away for free.

"Nothing's changed, I still have the same mentality," he told CNET after a Google Glasshackathon in San Francisco, implying that he's still willing, more than a decade later, to invest his personal time to help people even when he doesn't benefit directly.

But also by that time, the open source fan had received several other now-classic 1990s computer towers from friends. White's mom was not happy with their blocky, beige appearance and told him to reduce their numbers to one. Since they were running servers and he unwilling to get rid of them, White got into casemodding to make them more visually appealing.

Then the teenaged White learned how to run a business, experience he gained at 16 while managing Florida's Pinellas County Credit Union. Fast-forward two decades, and you get the current Brandyn White: a 27-year-old programmer working toward his Ph.D in computer science at the University of Maryland; co-founder of the computer vision consulting firm Dapper Vision; and developer and hacker who wants to change the world through Google Glass.

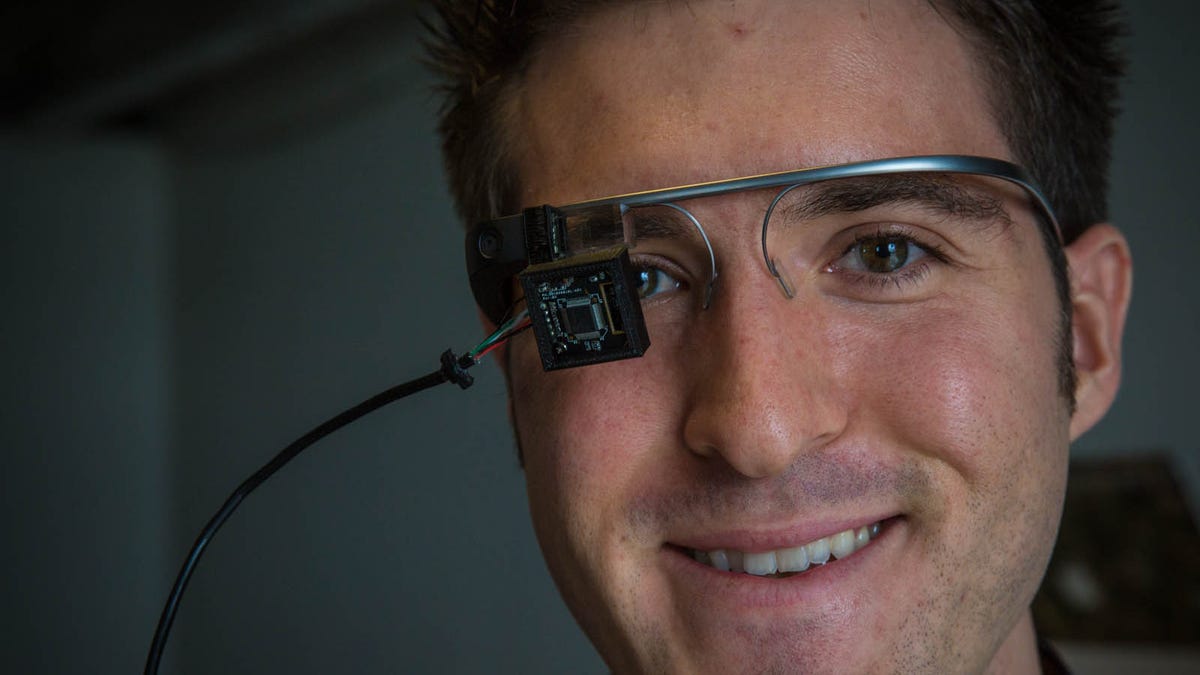

To that end, he's built an eye tracker hardware attachment for Glass. It adds eye-tracking features that the current Explorer Edition lacks, but he thinks it's destined to be much more than a kludgy prototype Glass peripheral.

Question: How did your interest in Glass lead you to eye tracking?

White: I've been very interested in wearables for a long time, and I'm interested in doing automatic recognition in visual systems. You have this problem where you want to use machine learning effectively, you need to be able to recognize lots and lots of little things. You need to know when you're in the kitchen, in the grocery store, when you're [physically] picking something up in the grocery store.

I'm interested in solving the problem of how to recognize daily activities such as shopping or driving.

My [Ph.D] research project is knowing everything about what you're doing, so that once I have that information I can add a lot of value. You just need to tack on to that data. For example, if we recognize that you are leaving the house and it is raining, we can remind you to bring an umbrella.

People have the sense that this is the creepiest thing in the world, so I want to build a database that's on their side and executes locally on their devices. It has strong cryptography, it's open source, and people know how their data is being used.

I want this to be your advocate, your agent. We want to set it up so that if we ever wanted to be evil, somebody could just fork it and set up something better.

Let's talk about why you built an eye-tracker for Google Glass. Why is it important? White: If you want things to line up between the real world and augmented reality, it helps to know where the person is looking. For accessibility applications, other form factors such as phones and wrist bands are difficult for some people to use, but most people can wear Glass. It's very hackable, it's very powerful, and its location allows it to sense the world from your perspective. Right now, there's no way to control Glass that's acceptable in a large group of people [in meetings or lectures.] Touching it [via the touchpad on the side] shows that you're not paying attention. You can't use voice commands, or pull out your phone.

Eye tracking, though, that's a use-case scenario and may be an interesting alternative.

Can't Google Glass be controlled with blinks? Isn't that the same as eye tracking? White: Blink gestures are a private feature [that most developers can't program for] but it's public enough that I can talk about it. It has an infrared emitter on the inside and proximity sensor, but you can modify it to do things like get the ambient reflection off your face, such as knowing when you blink. But you can't get real eye-tracking.

Blinks are not as good as looking at something with your eye. Using eye gestures are more generally applicable and intuitive such as looking at the left side of the screen to scroll left.

What's the benefit of eye gestures? What can they do that other input methods can't? White: I'm interested in helping people with disabilities. I've been trying to push computer vision researchers into accessibility more. If people took what they already know, it'd make an enormous difference. But there's no money in it, no grant money.

The reason that visual impairments are important to me is that in my background, computer vision, gets used for surveillance. And surveillance makes me feel bad. I've built technology that can detect things in the world. If I could tell you that there's a couch in front of you, that's almost never useful to you. But if you're blind, it may have some value. Another application that we've demonstrated is that a sighted person could wear Glass and verbally explain a scene: couch, table, and remote control. Then when a visually-impaired person wears it, Glass says what is in front of them.

Moreover, if we use the aggregate data, that could be useful in general such as having a timeline of your activities throughout the day.

So people who are unable to use their hands or voice can still use the Internet, through an eye-tracking enabled Glass. How did you get into building the eye-tracking hardware? White: My colleague in the MIT Media Lab Scott Greenwald introduced me to the Pupil Project, which has the goal of building an open source eye tracker. We started from their ideas and designs, and adapted it to work with Glass.

Right now it has to plug in to a host computer to perform the pupil and gesture recognition. We also need it to provide the power for the camera.

It's big and clunky [relative to Glass itself.] It works, and it cost $25. The goal is to make eye tracking available for developers to experiment with now to potentially motivate having it in a future device.

What's your stake in this? White: My goal is impact, not making money. Money is nice. I could work for Google and add a new feature to Glass, or I could make a video and impact the next version of Glass.

I'm putting myself into a position where I'm not making any money [on this project,] so I've been making my money consulting. I'd prefer to stay independent.

I'm part of the Glass research program, so I get fairly close access. I put out a video [two weeks ago] showing eye tracking. Everybody thinks Glass has it, but it doesn't. The reason I put it out was to show that it can be done, and how it can be useful.

Does Google Glass with eye-tracking constitute any kind of privacy violation? Won't this mean that Google just knows even more about you? White: Right now the rules say that you can't have ads on anything, but it's unavoidable. People are going to market back to you some other way.

So, ads on Glass are unavoidable? White: The worst thing that would happen in Glass would be to siphon off user data and sell them on things. That would kill off wearable computing. I want people to have applications on their device that know everything about their lives, and not be creepy about it.

It's not a bad thing that Glass or another personal device could know what I'm doing to better assist me in my daily life, it just requires a higher level of trust than we have now. It should go from I can check my email, which I can already do, to, "Oh, I can see how this can make my life better!"

Update, November 30 at 2:05 p.m. PT and 5:05 p.m. PT: Clarifies some of White's statements.