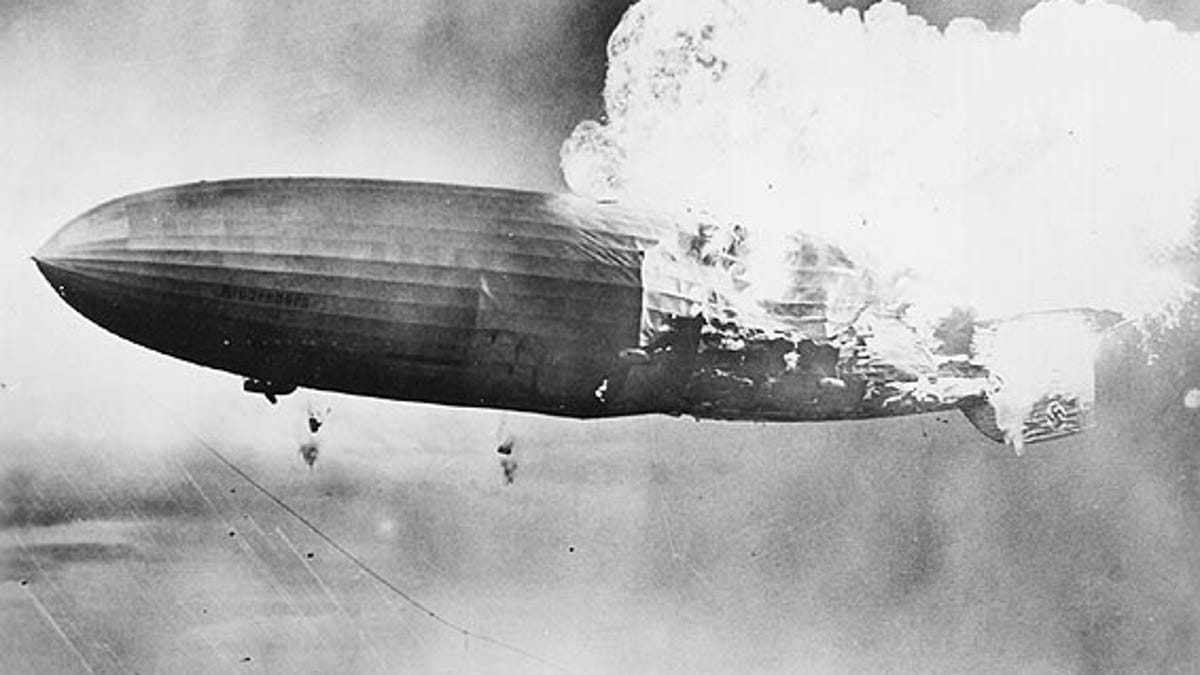

Hindenburg disaster 75 years ago abruptly ended zeppelin era

The great German airships flew the rich and famous around the world. But when catastrophe struck in Lakehurst, N.J., 35 perished and the era of luxurious travel by dirigible was over.

In Tom Clancy's sensationalist novel "Debt of Honor," a disgruntled pilot decides to avenge his lost honor by crashing a fuel-laden 747 directly into the U.S. Capitol, causing the giant building to explode and collapse. The scope of that fictional disaster was hard to fathom prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

But even before 9/11, anyone who had been in Lakehurst, N.J., on May 6, 1937, would have had a pretty good sense of just how big an explosion Clancy had in mind. Because that day, the Hindenburg, a German zeppelin that was famous the world over for ferrying the rich and powerful across the Atlantic, blew up as it attempted to land, a catastrophe that rocked the globe, kickstarted the news industry, and closed the book for good on a form of travel that, while far beyond the means of most people, unquestionably appealed to the romantic notions of the masses.

This Sunday marks the 75th anniversary of the Hindenburg crash, a disaster that killed 35 people and instantly became the world's most documented news event, bolstering the nascent radio business and making pre-movie news reels must-watch entertainment. And the reference to the U.S. Capitol isn't random. Not when you consider that the Hindenburg, at 803 feet from end to end, was longer than the 751-foot-long home of America's federal legislative bodies.

Yet the Hindenburg accident, as dramatic as it was, only put a sudden exclamation point on the already seemingly inevitable end of the era of the great zeppelins. In the years leading up to World War II, airplanes were already beginning to supplant the giant airships as a much more efficient and economical way to cross oceans.

"When the idea began to use large passenger zeppelins in the mid-1920s, it was a time when airplanes were really primitive," explained Daniel Grossman, an Atlanta lawyer who runs the Web site Airships.net. "But by the mid-to-late 1930s, when the Hindenburg was flying, aircraft technology had advanced in leaps and bounds. Pan Am had a flying boat that flew across the entire Pacific, and [there were] planes that could have crossed the Atlantic by the end of the '30s. So the Hindenburg would have been obsolete, even if it hadn't exploded. It could never have survived the competition."

The great zeppelins

There was a time, of course, when the zeppelins ruled the skies. Today, it's impossible to imagine a U.S. Capitol-sized aircraft emblazoned with swastikas flying slowly over American soil, but that was exactly the case prior to May 6, 1937.

In her fantastic book about World War II Army Air Forces Lt. Louis Zamperini, "Unbroken," Laura Hillenbrand told a tale that illustrated the power the great airships had in the 1920s and 1930s.

In the predawn darkness of Aug. 26, 1929, in the back bedroom of a small house in Torrance, Calif., a twelve-year-old boy [Zamperini] sat up in bed, listening. There was a sound coming from outside, growing ever louder. It was a huge, heavy rush, suggesting immensity, a great parting of air. It was coming from directly above the house. The boy swung his legs off his bed, raced down the stairs, slapped open the back door, and loped onto the grass. The yard was otherworldly, smothered in unnatural darkness, shivering with sound. The boy stood on the lawn beside his older brother, head thrown back, spellbound. The sky had disappeared. An object that he could see only in silhouette, reaching across a massive arc of space, was suspended low in the air over the house. It was longer than two-and-a-half football fields and as tall as a city. It was putting out the stars. What he saw was the German dirigible Graf Zeppelin. At nearly 800 feet long and 110 feet high, it was the largest flying machine ever crafted. More luxurious than the finest airplane, gliding effortlessly over huge distances, built on a scale that left spectators gasping, it was, in the summer of '29, the wonder of the world.

It's hard to imagine today, but the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg were, in their day, considered the ultimate way to travel. "There was a huge zeppelin craze in the late '20s," Grossman explained. "There were toys, newspaper cut-outs, zeppelin cups and saucers and china. It was like a zeppelin mania."

Indeed, Grossman said that Hugo Eckener, who had captained both the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg, had one of the most recognized names in the world. "This was an aircraft that was able to circle the globe at a time when most airplanes were rather flimsy wood and fabric contraptions that could barely hop a couple of miles," Grossman said, adding that when Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic in 1927, he did so in a one-person plane that was "basically a flying gas tank."

By comparison, the Hindenburg was the lap of luxury, and starting with its debut in 1936, took people like actor Douglas Fairbanks, Walter Chrysler, boxer Max Schmeling, and many others across the Atlantic in comfort and splendor. The great dirigible featured 34 cabins, a lounge, a writing room, a dining room, a piano, and more.

And while the hoi polloi could never afford a flight, that didn't stop the masses from loving Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin's airships.

The first of the zeppelins took air in 1900, the Lenbarker Luftfahrzug. In the early days, rather than having the large, roundish, and fairly rigid shape of the Hindenburg, the first models more resembled pencils and were meant to flex, much like an accordion.

Over time, zeppelins took on their more familiar shape, and all told, the Germans built 119, with a total of 130 planned. And in addition to their civilian utility, they were also heavily favored by the German--and later, American--military: The airships were heavily involved in bombing London during the first blitzes of World War I.

The end

No one knows exactly what caused the Hindenburg to explode. But on that day in May 1937, Lakehurst, N.J., was being roiled by electrical storms, Grossman said, causing some local rubber factories to shut down for fear of lightning igniting rubber dust. "At the most elemental level, the hydrogen ignited," Grossman explained. "It was just crazy and dangerous to operate a ship that had 7 million cubic feet of fuel. It's a flying bomb."

Grossman said that although it's not known how it happened, it's agreed by Hindenburg experts that some of the airship's hydrogen escaped and met a spark, causing disaster.

The Hindenburg was attempting a landing where the ship was 200 feet off the ground and had dropped down a landing line. But up at the zeppelin's level, a lot of sparks were flying, he said. Grossman said that a common, though unprovable, theory is that because the Hindenburg had had to do a very tight turn to land, pointing its nose into the wind, a bracing wire may have snapped and sliced through a gas cell. "Whether it was a snapping wire, or whether the gas bag had a leak already," Grossman said, "somehow you had hydrogen that was uncontained. And if you mix oxygenated hydrogen with a spark, you get a big bang."

Even today, however, there are people who can't accept that hydrogen was to blame for the explosion, Grossman said. Instead, some argue that the Hindenburg's skin was flammable. This is an urban myth that endlessly annoys the small fraternity of so-called "Helium Heads," or zeppelin experts, Grossman said. "You have all these supporters of hydrogen energy [who] argue that the Hindenburg disaster was not because of hydrogen."

Either way, that day 75 years ago come Sunday put a very abrupt end to one of the most dominant forms of passenger air travel. And that was a shame.

"What's more romantic than spending two days traveling quiet and low," Grossman said of the Hindenburg. "You could see icebergs, and whales...You're sitting in a dining room with wine. It's the complete opposite of flying across the Atlantic on Delta."