Hidden Mars 'lakes' may actually be frozen clay, scientists say

In 'knockout' find, researchers have a compelling alternative explanation for what seemed to be hidden pools of liquid water.

The Martian south pole is a mysterious place.

There's an intense mystery brewing under the icy cap of Mars' south pole region. Studies from the last few years have suggested there could be brackish lakes of liquid water hiding under there, but new research is bringing a different explanation to the table. Maybe it's frozen clays.

A NASA-led study from June called into question the lakes idea, but left it open as to what might be there instead. A new study published in Geophysical Research Letters in mid-July says frozen clays could be a good interpretation of radar data from the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter's Marsis instrument.

Some researchers had interpreted the data -- which appeared as bright radar reflections -- to indicate sub-glacial pools, which led to various ideas as to how the frigid south pole might harbor liquid water. Explanations included high amounts of salt or perhaps volcanic activity.

Planetary Science Institute research scientist Isaac Smith is the lead author of the new paper and he calls the research "a knockout" to the liquid water interpretation. "Now, our paper offers the first plausible, and considerably more likely, alternative hypothesis to explain the Marsis observations. Specifically, solid clays frozen to cryogenic temperatures can make the reflections," Smith said in a PSI statement on Thursday.

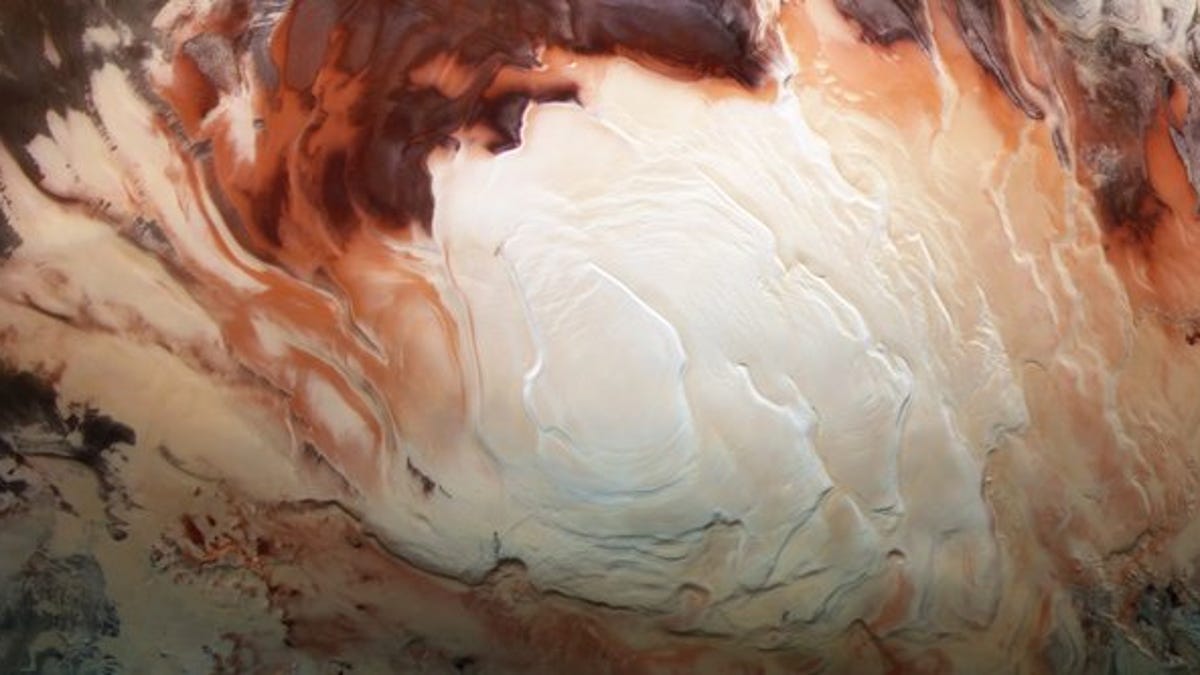

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter captured this view of ice sheets at Mars' south pole. MRO also detected clays near this ice.

The idea of liquid water under the surface of Mars is cool all on its own, but it's been extra tantalizing because the presence of water can be friendly to microbial life. NASA's Perseverance rover is currently scouring a now-dry ancient lakebed looking for signs of microbes from the deep past. We may have to tamper our enthusiasm for what might possibly be lurking in the south pole.

The new research points specifically to smectite clay. "Smectites are a type of clay that is extremely abundant on Mars, covering nearly 50% of the surface, especially focused in the southern hemisphere. I call them solid state to reinforce the idea that these materials are solid," said Smith, who noted this type of clay is brittle at cryogenic temperatures, rather than soft like clay used in pottery.

The team members went beyond just analyzing data. They conducted an experiment in freezing smectite clay and discovered the super-chilled material could be responsible for the same sort of radar reflection observations seen by Mars Express.

The researchers also used data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that found smectites in the region of the Martian south pole. Put it all together and you get a compelling argument for clays rather than liquid water.

While the no-lakes concept might sound disappointing, it's a sign of science working as it's supposed to. Since we can't just pop over to the Martian south pole and dig, we have to work with the data that's available, and it's up to researchers to sort through the possible explanations for what they're seeing.

"In planetary science, we often are just inching our way closer to the truth," said Martian polar scientist Jeffrey Plaut in a NASA statement on Thursday. "The original paper didn't prove it was water, and these new papers don't prove it isn't. But we try to narrow down the possibilities as much as possible in order to reach consensus."

Follow CNET's 2021 Space Calendar to stay up to date with all the latest space news this year. You can even add it to your own Google Calendar.