Hearing on Gizmodo iPhone warrant scheduled

Judge will hear dispute between media organizations and prosecutors on unsealing records concerning the criminal investigation into what may have been a prototype iPhone purchased by Gizmodo.

A judge in Silicon Valley will hear arguments later this week in a dispute over unsealing records about the criminal investigation into what may have been a prototype iPhone purchased by a gadget blog.

San Mateo County Judge Clifford Cretan has scheduled a hearing for 9 a.m. PDT Friday in his courtroom in Redwood City, Calif. Cretan previously approved a police request to search the home office of Gizmodo editor Jason Chen, a decision that unleashed a torrent of speculation about the legality of searching a journalist's workplace and whether Apple instigated the raid.

Media organizations including CNET, the Associated Press, and Bloomberg are planning to ask Cretan to unseal an affidavit prepared by a San Mateo County detective asking to search Chen's home. The coalition says that under California law, the affidavit became a public document after 10 days and that its release could reveal whether prosecutors followed proper procedures when searching a newsroom.

The San Mateo County district attorney is opposing the request. In an four-page legal brief (PDF), prosecutors say the media's First Amendment right does not "outweigh the rights of the people to protect the identity of persons who may have provided information to law enforcement in confidence during the initial stages of the investigation."

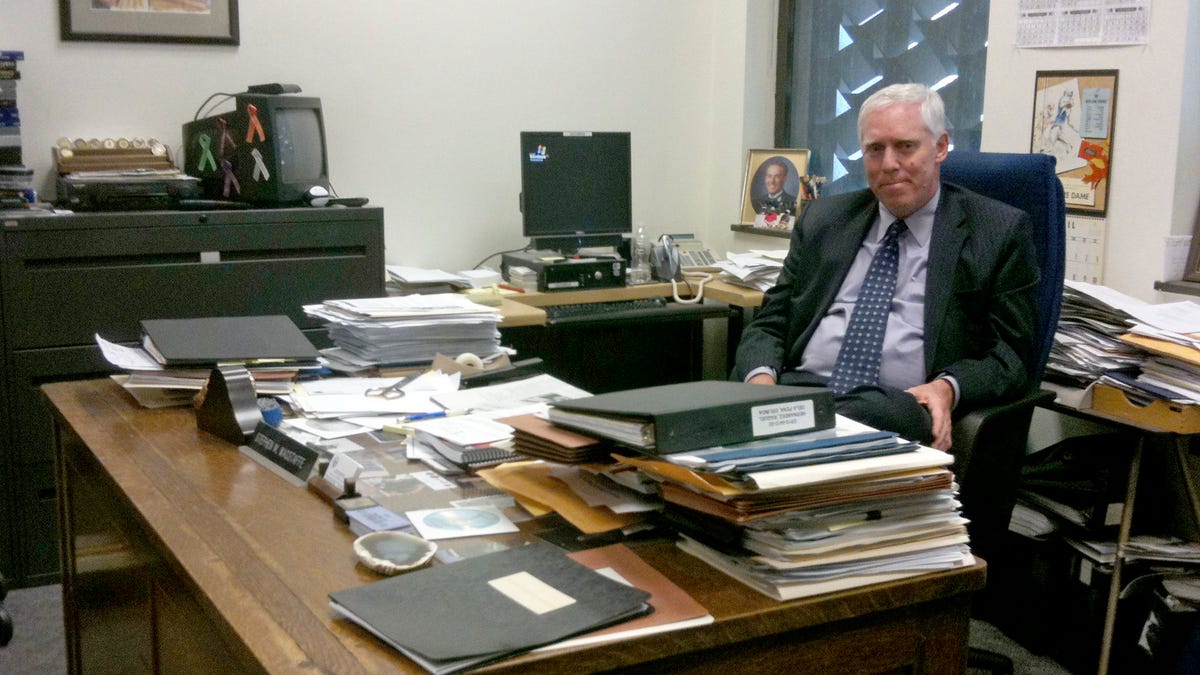

Prosecutors did not say in the brief who these informants are, and chief deputy district attorney Stephen Wagstaffe did not elaborate in an interview last week. In addition to the documents themselves remaining under seal, in a highly unusual move, Cretan's order designating them as off-limits to the public also appears to be secret.

Wagstaffe has told lawyers for the media coalition that he would not agree to redacting names from the affidavit and other sealed court documents. It was not clear on Tuesday whether an attorney for Brian Hogan, the 21-year old Silicon Valley resident who has acknowledged finding the device, would oppose the request.

Other members of the media coalition are the Los Angeles Times, Wired.com, the California Newspaper Publishers Association, and the California-based First Amendment Coalition.

On Thursday, the coalition had asked the presiding judge, Stephen Hall, to unseal the documents. But he assigned the case to Cretan in a brief order (PDF) that said, without elaborating, that it was necessary "for the purposes of judicial economy and to ensure that the competing interests of the parties involved in the criminal investigation (and) the press are properly balanced."

In general, searches of newsrooms are unlawful and can even result in police paying penalties in the form of damages to media organizations. A federal law called the Privacy Protection Act broadly immunizes news organizations from searches. A similar California law prevents judges from signing warrants that target writers for newspapers, magazines, or "other periodical publication"--a definition that a state appeals court has extended (PDF) to Apple bloggers.

On the other hand, if the news organization is suspected of a crime, a search of its newsroom or its employees' home offices could be permissible. The federal Privacy Protection Act includes some exceptions for criminal activity. In California, although the anti-search law does not have an explicit exception, at least one court has suggested that the protections do not extend to journalists suspected of a crime.

California law says that search warrants "shall be open to the public as a judicial record" no later than 10 days after a judge signs it, which would have been last Monday. The search warrant affidavit was prepared by Detective Matthew Broad of the San Mateo County Sheriff's Office.

Background

The story began in March when Gray Powell, a 27-year-old Apple computer engineer, forgot what may be a 4G iPhone phone at a German beer garden in Redwood City, Calif., after a night of drinking. According to a Wired.com report, Brian Hogan acknowledged finding the phone. With the help of friends, Hogan allegedly approached multiple tech news sites before finally selling the handset to Gizmodo for $5,000. (Sage Robert Wallower, a 27-year-old University of California at Berkeley student, was one of those friends who contacted technology sites, sources have told CNET.)

Prosecutors in the case say they are conducting a felony theft investigation, but no charges have been filed. Police have interviewed Hogan and one other unidentified man in connection with the sale to Gizmodo.

On April 23, just hours after CNET reported that Apple had contacted law enforcement officials about the phone and an investigation was under way, police showed up at Chen's home in Fremont, Calif., across the bay from San Francisco. After breaking down his door, they confiscated three Apple laptops, a Samsung digital camera, a 32GB Apple iPad, a 16GB iPhone, and other electronic gear, according to documents that Gizmodo posted.

Apple ranks among the most security-conscious companies and has gone to great lengths to prevent leaks about its products. To secure trade secrets, the company has not shied away from high-profile courtroom fights. It filed a lawsuit against a Mac enthusiast Web site Think Secret, for example, to unearth information about a leak. A state appeals court ruled in favor of the Web site.

In that case, Apple argued that information published about unreleased products causes it significant harm. "If these trade secrets are revealed, competitors can anticipate and counter Apple's business strategy, and Apple loses control over the timing and publicity for its product launches," Apple wrote in a brief.

Under a California law dating back to 1872, any person who finds lost property and knows who the owner is likely to be--but "appropriates such property to his own use"--is guilty of theft. There are no exceptions for journalists. In addition, a second state law says any person who knowingly receives property that has been obtained illegally can be imprisoned for up to one year.

Knowing that an item probably belonged to someone else has led to convictions before. "It is not necessary that the defendant be told directly that the property was stolen. Knowledge may be circumstantial and deductive," a California appeals court has previously ruled. "Possession of stolen property, accompanied by an unsatisfactory explanation of the possession or by suspicious circumstances, will justify an inference that the property was received with knowledge it had been stolen." California law says lost property valued at $100 or more must be turned over to police.

CNET's Greg Sandoval contributed to this report

Full coverage: Lost iPhone prototype spurs legal action