Google patent application reveals broadband dreams

The Net giant tries to patent a technique for using a flat, flexible housing to lower the cost of bringing a super-fast Internet to homes. Just how big will Google Fiber be?

Apparently Google has put some thought into this idea of bringing super-fast fiber-optic broadband to Kansas City.

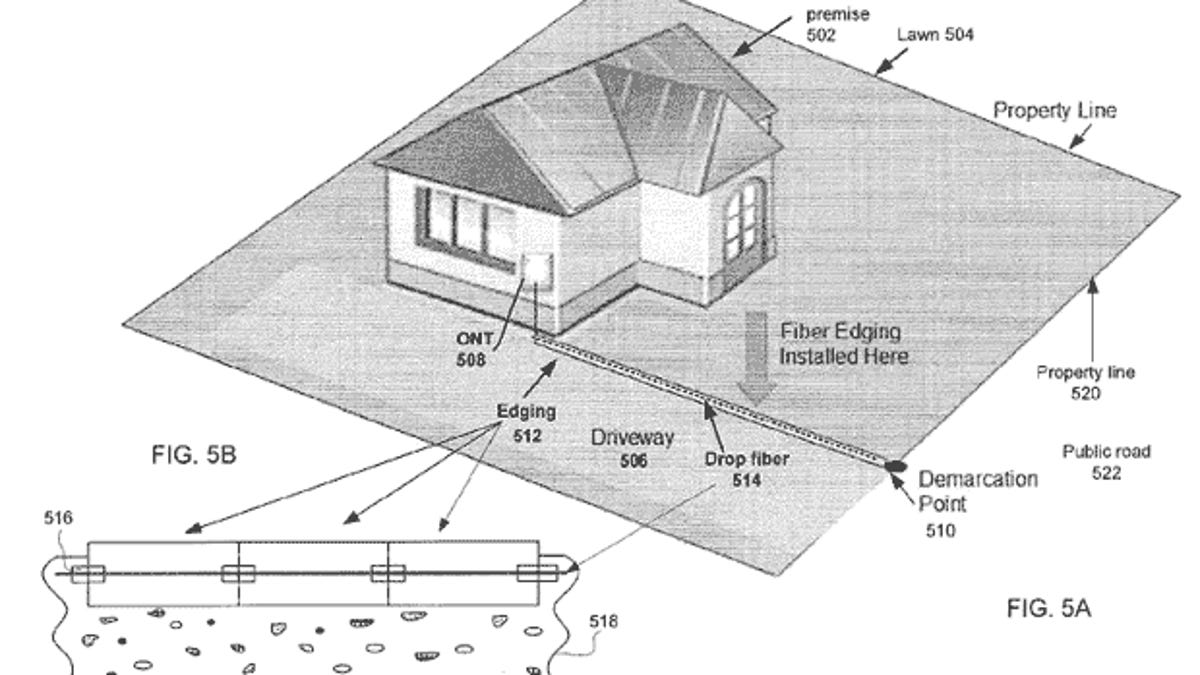

The company has applied for a patent for "general edging systems and methods," which the application bills as "a low-impact, convenient, time-efficient and cost-saving optical fiber deployment technology."

The application describes a flat, perhaps bendable strip of "edging" that carries fiber-optic lines or coaxial cables tucked within. The edging could be slipped into a shallow slot, perhaps along a fence or driveway or dug into a lawn, or it could be camouflaged to fit into the garden or patterned to look nice if exposed.

Another idea in the application: the edging could come in several sections that snap together. Or it could be made hollow with a sealed tube through which fiber-optic lines could be blown after the housing is installed.

Nobody ever accused Google for not thinking big, and perhaps the patent application sheds some light on how ambitious it thinks Google Fiber can go beyond Kansas City, Kan. and Mo. Everybody loves the tremendous data capacity of fiber-optic lines, but so far it's mostly been economical only for long-haul lines where its installation expense pays off.

Cheaper and faster installation could make it more economical to bring fiber-optic lines all the way to people's houses (fiber to the home, or FTTH). That would make it easier for Google to fulfill its dreams of fast, cheap Internet access everywhere. The Kansas City testbed will have speeds of 1 gigabit per second -- something like 100 times what higher-end plans today offer -- and there was a report last year that Google Fiber could extend to Europe.

In Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt's speech at Mobile World Congress this week, he said, "By 2020, fiber networks will be deployed in nearly every city," and of course he expects Google services to be riding atop those networks.

"The Web will be everywhere, but it'll also be nothing. It'll be like electricity. It'll just be there," he said.

It's unclear just how much Google hopes to profit directly from Google Fiber. Faster Net services mean more searches, more advertising, and more customers for Google Apps, so -- like Android -- Google Fiber can be seen as an ennabler for Google's current businesses.

Google won't comment on its specific plans, but Google Fiber project leader Kevin Lo said in 2011, "This is a business for us. We expect to make money. We don't expect to lose money ... This thing has to make economic sense, and it does."

Building and operating Net infrastructure also could give Google a bit of moral high ground, or at least bargaining power, in its struggle to keep telecommunications companies from trying to get Google, with data-intensive services such as YouTube, to shoulder some network infrastructure costs. With Google Fiber, the company becomes a network operator, too.

Google bears the brunt of telcos' criticism of "over-the-top" players who send data over networks and generate an outsized portion of the profits. Some of that concern was on display at Mobile World Congress, for example from Sunil Bharti Mittal, president of Indian wireless network operator Airtel.

"When somebody watches YouTube on a mobile phone and ends up [with a] big bill, he curses under his breath at the telecom operators. But YouTube is consuming a massive amount of resources on our network. Somebody's got to pay for that," he said. YouTube should pay operators an "interconnect charge" to fund the network improvements, he said.

Schmidt expressed sympathy for the operators' plight.

"I'm very sensitive to these arguments because i think they're true," Schmidt said. "It's very difficult to be a telecom operator right now. You have a tough regulatory environment [which means] It's difficult to raise your data plan [prices]. You have to [upgrade] your equipment to 4G. You have customers who are busy using enormous amounts of the bandwidth that's so scarce for you. Governments, in addition to regulating you to death, charge huge fees for new spectrum" for wireless services.

"We at Google are critically dependent on this infra building out. We're trying to be respectful of the very real problem that the operators have," Schmidt said.

Via FierceCable, via Kansas City Star