Google finds no privacy on private roads

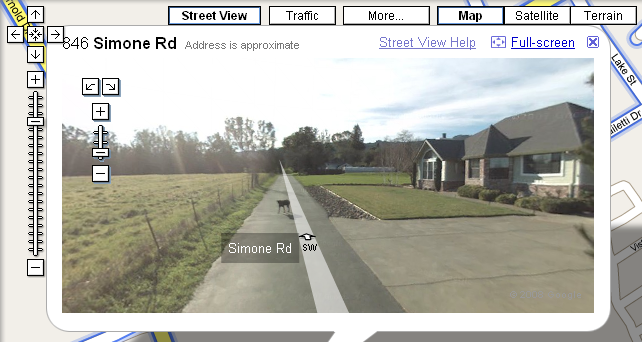

Residents in Northern California are complaining that drivers hired to collect the images for Google's Street View are disregarding private property signs and driving up private roads.

Google's Street View service apparently thinks your "no trespassing" and "private road" signs are just for decoration.

The service, which gives Web users a driver's perspective of hundreds of cities around the world, has raised the ire of residents who say the images are an invasion of their privacy. Now residents in California's Humboldt County are complaining that the drivers who are hired to collect the images are disregarding private property signs and driving up private roads.

In an episode reported recently by the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, a Street View driver cruised past two "no trespassing" signs to collect images of a residence that is 1,200 feet from the public road.

"It isn't just a privacy issue; it is a trespassing issue, with their own photos as evidence," resident Betty Webb told the newspaper. "They really went off the track to get to our address."

Webb's experience apparently is not an isolated incident: the newspaper used digital maps provided by the county of Sonoma and found Google had photographed along more than 100 private roads.

Google told the newspaper that, while it has the right to photograph from private roads, it tries to avoid it.

"Our policy is to not drive on private land," spokesman Larry Yu said, adding that the company hires local drivers who are given specific routes to follow. Yu retracted that statement when the newspaper told him of a driver who said he was simply told to just drive around the county and collect images.

Google's claims to be legally allowed to photograph on private roads stems from its assertion that privacy no longer exists in this age of satellite and aerial imagery.

"Today's satellite-image technology means that...complete privacy does not exist," Google said in its response to a complaint filed in April by a Pittsburgh couple that sued Google when photographs of their home appeared on the site.

Indeed, Google appears adamant that its right to photograph streets trumps individuals' right to privacy. Internet pioneer and Google evangelist Vint Cerf told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in May that "nothing you do ever goes away and nothing you do ever escapes notice." Then, in what the newspaper described as an "intentionally flippant moment," Cerf added, "There isn't any privacy, get over it."

Cerf may have been channeling former Sun Microsystems' CEO Scott McNealy, who said, "You have no privacy. Get over it" in 1999. Either way, Cerf explained himself on Google Blogoscoped: "It was intended to be partly in jest and partly irony...I was trying to suggest that we really have entered a period when things are a lot less private. Think of the ease with which photos and videos can be taken, digitized, shipped around on the Internet, posted on YouTube or its equivalent."

This is not the first time Google has been caught on private streets. In January, a private Minnesota community near St. Paul, unhappy that images of its streets and homes appeared on the site, demanded Google remove the images, which the company did.

Not long after the feature launched in May 2007, privacy advocates criticized Google for displaying photographs that included people's faces and car license plates. In May, the company announced that it had begun testing face-blurring technology for the service.