Facebook's $1 messages: One more way to get your credit card

The latest update to Facebook Messages did more than just change a few settings. It's also a sign of the social network seeking yet an opportunity to encourage impulse purchases.

Facebook, which began the year with a reputation for caring more about its users than about making a buck, is ending the year with the rollout of yet another way to try to squeeze more money from its members.

This latest money-making effort comes with a revamp of its popular Messages service -- that part of Facebook through which you can message/e-mail your "friends" and, in fact, those who aren't your friends. What's changing -- and a spokesman describes it to CNET as a "small experiment" -- is that Facebook will start charging some people for messages they want to send to people they're not friends with.

The $1 cost seems steep just to shoot someone a message, but no matter. Facebook will surely drop the price if no one uses it. But the bigger point: This latest "test" shows that Facebook, eager to prove to Wall Street that it's building a cash-generating empire, is looking for more ways to add revenue streams not tied to advertising and, importantly, is trying to get more user credit cards on file.

Unlike some other titans of consumer tech -- namely, Apple and Amazon -- Facebook has a vast wealth of data about all of us but relatively few credit cards. Most of the credit card numbers it has -- a number it won't disclose -- it's accumulated from people who play games and pay up for virtual items. But that's far from enough for Facebook's ambitions.

The company has recently added other features that require credit card, and so far Facebook has given no indication for how those are going. In October, for instance, it started letting people pay $7 to promote a post. And earlier this month, it opened up Facebook Gifts to all U.S. users and added a range of new retail partners so that users can send friends everything from wine to clothes from BabyGap -- provided, of course, they enter a credit card. Anyone who's tried it might notice that Facebook doesn't take PayPal. Then, the next time you decide to buy a gift, your information card information pops up and is ready to go.

This is the way Facebook wants it, particularly if it rolls outs more services and offers that people can pay for through their phones. The more credit cards Facebook has on file, the more likely mobile users will send gifts or whatever else Facebook has in store as part of its business plan.

Facebook's messaging effort hardly seems like a slam dunk. To be fair, Facebook seems to be tip toeing into this, probably aware that some people might get annoyed if strangers are suddenly blasting them with messages. The pay-to-message experiment comes as part broader changes to Facebook's messaging system, which today is rolling out to every user worldwide. It's all a bit confusing in that Facebook sort of way.

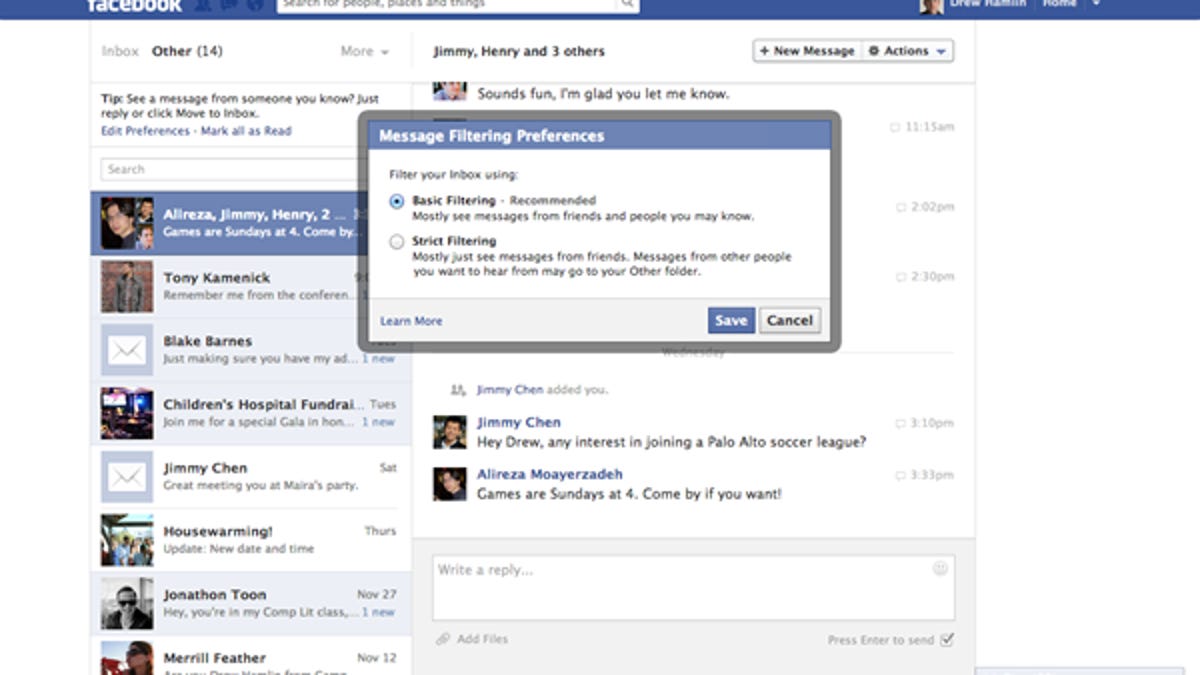

Before these changes, users could send messages to strangers unless those people set restricted privacy settings, something Facebook says most people don't do. Under the new system, users can message anyone regardless of their privacy settings; the messages end up in a folder labeled "other," which is designed to catch spam. That's where the money comes in. To bypass the recipients "other" folder, users can pay $1 to make sure their messages end up in a person's main inbox. (This is not currently available for Pages, only individual Facebook members).

There is no way to opt out of this newly updated Messages system. The only way not to get messages from strangers is to block them after the fact. While those who don't want to message strangers may find the $1 messaging service odd, there are others who may find the option handy.

Facebook argues it would be useful if you were, for example, planning a surprise party for a friend through Facebook. Four of the five people you are inviting to this party are friends with you as well, but one is not. You could make sure the fifth person gets the invite in their Inbox, instead of the "other" folder, by paying the $1. Additionally, there are people -- recruiters, job seekers, public relations folks or (ahem) journalists -- who use Facebook to network.

Facebook won't say how many people use the messaging now or how many people send messages to users who aren't their friends. But if it rolls it out worldwide and only a small portion of Facebook's billion-plus members decide this is a worthwhile, there's still plenty of potential -- both for cash and credit.