Extinct megalodon confirmed as the biggest fish in the sea

In case Jason Statham wasn't already nervous enough.

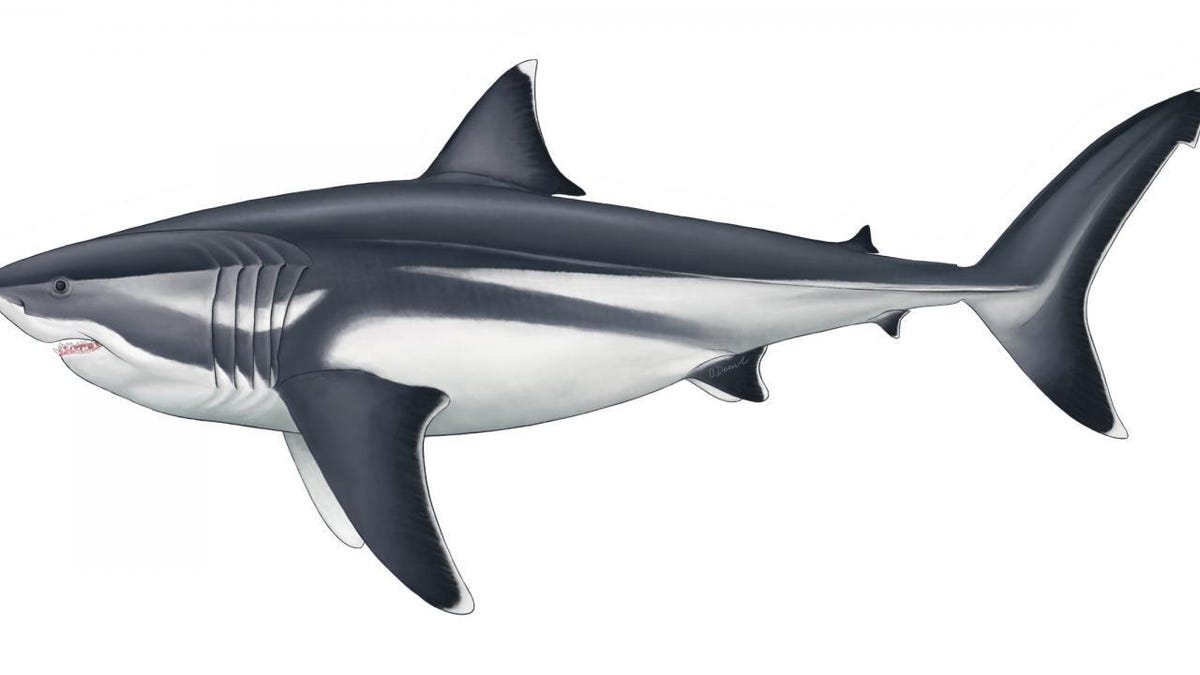

This is an illustrated reconstruction of an adult megalodon.

Of all the living fish in the sea, the whale shark is the biggest. With an average adult length of 8 to 9 meters (about 28 feet), it eclipses all other sharks in the ocean today -- and females reign supreme in the size stakes. But that certainly wasn't always the case, as scientists have confirmed.

Published Sunday in the journal Historical Biology, a study calculates that the now-extinct Otodus megalodon, or megatooth shark, once reached up to 15 meters (49 feet) in length, easily surpassing the present-day whale shark.

Generally portrayed as a gigantic monster of a shark in films like 2018's The Meg, the real megalodon was a far cry from the 75-foot beast that made cinema-goers shriek. Regardless, the megalodon certainly was the biggest fish in the sea for a while.

Researchers calculated the shark's length by using measurements taken from present-day lamniforms (the shark group to which the megalodon belonged) to estimate the body length of extinct forms, all through evaluating teeth. It also showed that the megalodon's size was an outlier, doubling the general limit of smaller lamniforms.

"Lamniform sharks have represented major carnivores in oceans since the age of dinosaurs, so it is reasonable to assert that they must have played an important role in shaping the marine ecosystems we know today," Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

Michael Griffiths, a co-author and professor of environmental science at William Paterson University in New Jersey, called the research "compelling evidence for the truly exceptional size of megalodon."