Encryption, the FBI's bane, nets top prize for computing pioneers

Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman's privacy-protecting technology has become both an inextricable part of modern life and a scourge to law enforcement.

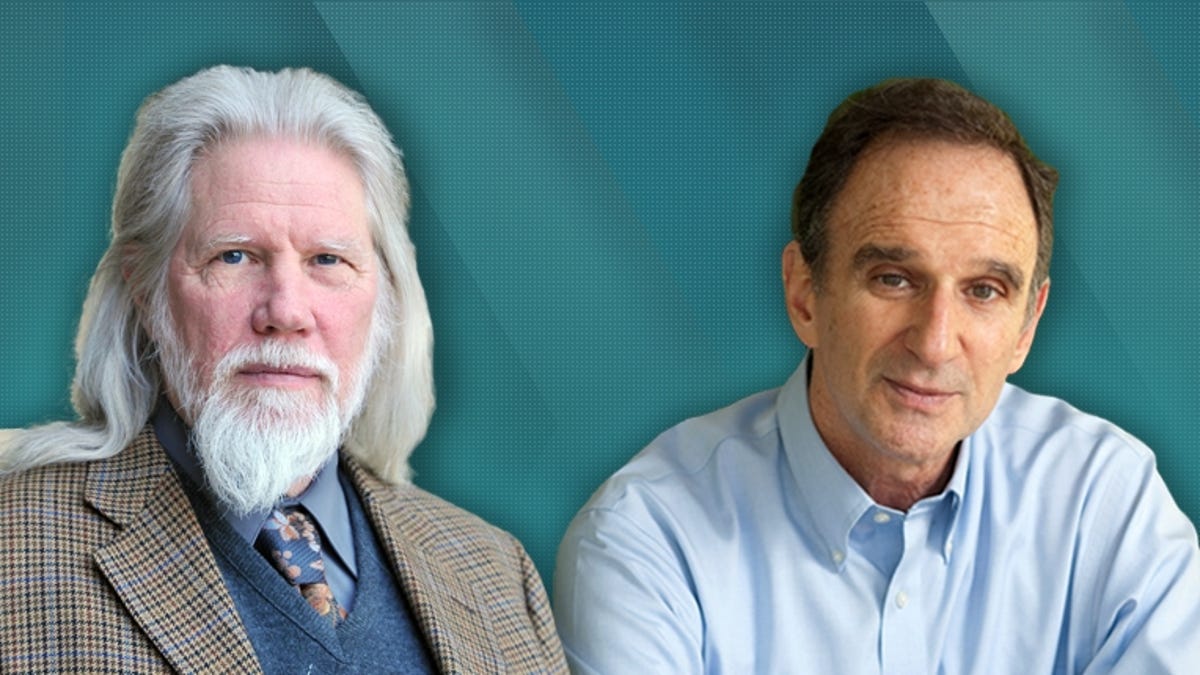

Whitfield Diffie, left, and Martin Hellman invented the public key encryption technology that's now the foundation for many forms of private communications.

The FBI may have mixed feelings about this award.

Encryption, the technology that makes it possible to buy shoes on the Internet and send private messages to your doctor, is under attack from politicians and law enforcement officials who hate that it also shields the communications of criminals and terrorists.

Yet there's no doubt the tech industry considers encryption a major achievement. On Tuesday, two pioneers of today's encryption technology were named winners of the $1 million A.M. Turing Award, the computing industry's equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Four decades ago, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman invented an encryption technique called public key cryptography.

"In 1976, Diffie and Hellman imagined a future where people would regularly communicate through electronic networks and be vulnerable to having their communications stolen or altered. Now, after nearly 40 years, we see that their forecasts were remarkably prescient," Alexander Wolf, president of the Association of Computing Machinery professional organization, said in a statement Tuesday.

The award spotlights how even the most arcane technology can affect our daily lives now that computing technology is deeply embedded in everything we do. Encryption powers e-commerce, lets business partners chat securely across the globe, and protects the privacy of spouses discussing their marriage. Even as politicians and law enforcement push for a way past encryption, US Defense Secretary Ash Carter said the US military uses encryption on a massive scale and calls strong encryption a "good thing."

Encryption has been in the spotlight over the past two weeks in the legal battle between the FBI and Apple over investigators' inability to retrieve encrypted information from a passcode-protected iPhone used by a terrorist in a December attack that killed 14 people in San Bernardino, California. The FBI wants any evidence it can find and is pushing Apple to build software to help it unlock the phone. Apple, though, has embraced stronger encryption to protect privacy and argues that building the software for the FBI would "undermine the basic security and privacy interests of hundreds of millions of individuals around the globe."

Apple has powerful allies including Google, Microsoft and Facebook, all of them stung by Edward Snowden's revelations of extensive US government surveillance of average Americans.

Apple also has critics, including Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who calls encryption "the Achilles' heel of the Internet." FBI Director James Comey argues that encryption means sources of information are "going dark."

Encryption, a centuries-old craft, scrambles communications so only the sender and recipient can understand them. A secret code called a key is used to scramble the messages, and for most of the history of encryption, the sender and recipient each had to know that key.

The Diffie-Hellman approach, though, uses a specially matched pair of keys, one secret and one publicly known. That's essential when a sender and recipient don't know each other in advance, like when you want Amazon's website to keep your credit card number secret but haven't had the time to drop by Amazon's headquarters to arrange a mutually agreeable password.

With public key cryptography, a message can be encrypted using a recipient's public key then decrypted with the private key, which only the recipient has. And with communications going the other direction, a sender can encrypt a message with a private key, which is in effect an electronic signature that guarantees the authenticity of the sender.

The Turing award is named after UK computer technology pioneer Alan Turing, who was instrumental in cracking the German Enigma code in World War II. Diffie, 71, researched security matters for years at Sun Microsystems, where he was chief security officer, and Hellman, 70, is professor emeritus of electrical engineering at Stanford University.