Dev: Used game sales are 'destructive' to industry

Pre-owned video games sales don't make Codemasters CEO Rod Cousens happy. He wants retailers and publishers to work together on a solution that satisfies both parties.

Whenever you buy a pre-owned game, at least one developer cringes.

In a GamesIndustry.biz interview published this week, Codemasters CEO Rod Cousens said that the sale of pre-owned games in retail outlets around the world is hurting the video game industry and that a solution is needed sooner rather than later.

"Pre-owned isn't actually new--in 1981 there was Buy and Try, and that type of stuff," Cousens told the gaming publication. "The difference was that it wasn't a significant percentage of the market, and it was never promoted as aggressively through the retail community as it is today."

Cousens went on to say that such promotion has helped pre-owned game sales and subsequently has hurt sales of the most popular games. Even worse, it apparently hurts how developers make games.

"The way it's structured today is destructive, and it's negative to creativity and innovation," Cousens said. "I believe it has to be managed. There's an element of it which is acceptable, and there's an element that isn't."

Of course, finding a middle ground between developers and publishers that don't want to see pre-owned sales cut into their revenue and retailers that are relying upon pre-owned games to buoy their own sales can be difficult.

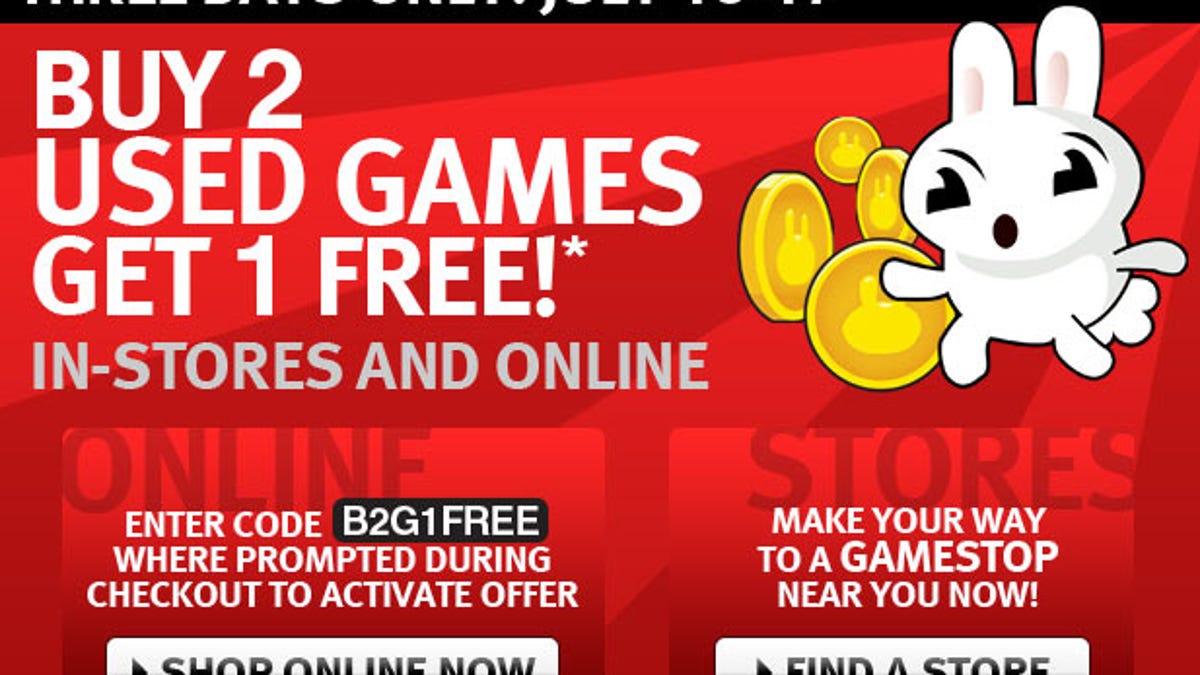

Currently, GameStop, the top boutique video games retailer in the U.S., is generating massive amounts of revenue from used games. During the second quarter, it generated $565.5 million in used video game product sales. It turned a $260 million profit on those sales, representing over 50 percent of its total gross profit of $516.8 million.

GameStop isn't alone in selling pre-owned titles. Wal-Mart offers several used games on its Web site. Best Buy also sells pre-owned titles.

But developers and publishers only get royalties from the sale of new titles. And that is something that companies have been taking issue with for quite a while now.

Over the summer, THQ creative director Cory Ledesma, told CVG in an interview that he hopes "people understand that when the game's bought used we get cheated." His comments were made as the company implemented a one-use code to play online in Smackdown Vs. Raw 2011. He told the gaming publication that he didn't "really have much sympathy" for used-game buyers who wanted the "online feature set."

THQ isn't alone. Electronic Arts has a program called Online Pass that launched earlier this year with Tiger Woods PGA Tour 11. The program provides a one-time-use code with each copy of several of the company's games. Once users input the code, they have the ability to "have access to multiplayer online play, group features like online dynasty and leagues," and more.

However, if a person sells that game back to a retailer and someone else buys it used, the second buyer cannot use that code to play online themselves. If they plan to play online, they will need to pay $10 for access to the title's online features.

"We want to reserve EA Sports online services for people who pay EA to access them," Andrew Wilson, EA Sports senior vice president of worldwide development, wrote on the company's page describing its Online Pass program.

During its second-quarter earnings call earlier this year, Activision also took aim at used-game sales. The company said that it's "limiting supply" of downloadable content to pre-owned titles. The company said that it will also explore other options to curb the impact used-game sales are having on its operation.

But consumers also play into this. Used games are cheaper than their new counterparts, which typically sell for anywhere between $50 or $60. And during a recession, saving money is paramount in the minds of many people. Stopping them from choosing the cheaper option could be an extremely difficult proposition for the gaming industry.