Deepfakes are a risk to 2020 elections, experts tell Congress

Facebook global policy chief says addressing manipulated videos is a top priority.

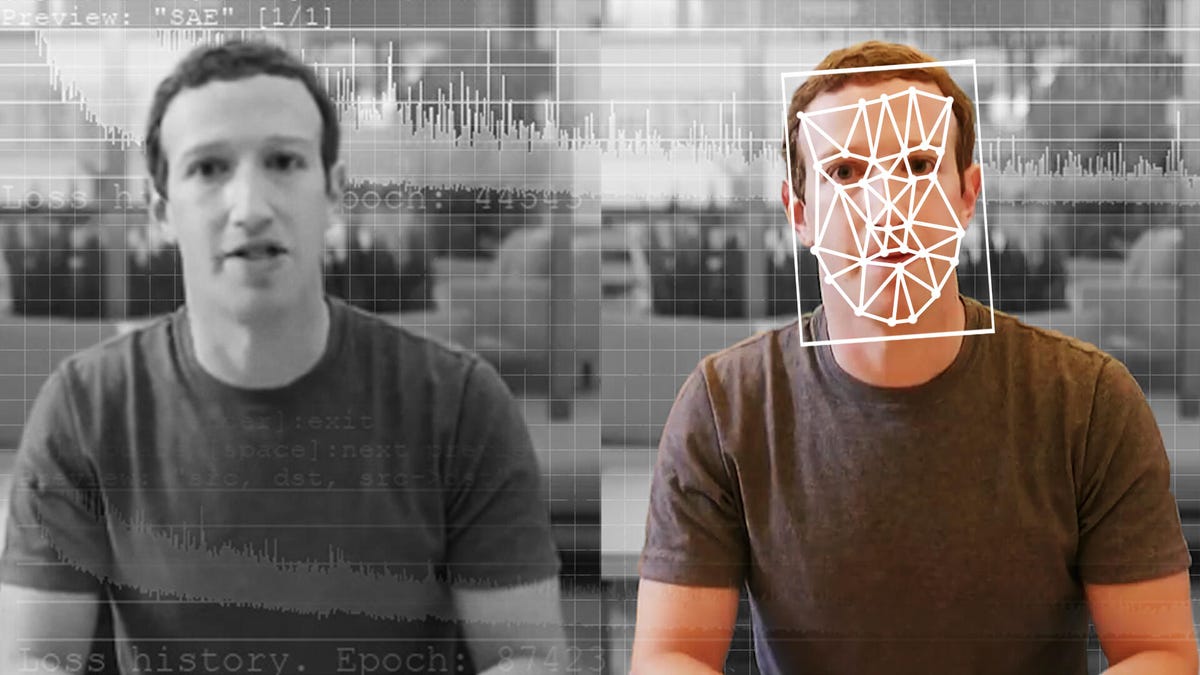

A comparison of an original and deepfake video of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Deepfakes and other manipulated videos put the integrity of democratic elections at risk, a group of experts told the House Committee on Energy and Commerce Wednesday. What to do about it is a thorny question.

A hearing, titled "Americans at Risk: Manipulation and Deception in the Digital Age" and held by the subcommittee on Consumer Protection, focused on the wide range of online fraud and manipulation on the internet. Monika Bickert, the vice president of Facebook global policy management, was joined by three other experts on the topic. They were Joan Donovan, a research director at the Harvard Kennedy School, Tristan Harris, executive director at the Center for Humane Technology, and Justin Hurwitz, an associate professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law.

"While these videos are still relatively rare on the internet, they present a significant challenge for our industry and society," Bickert told lawmakers in written remarks. "Leading up to the 2020 US election cycle, we know that combating misinformation, including deepfakes, is one of the most important things we can do."

The hearing comes amid mounting concerns that deepfakes -- manipulated video made with artificial intelligence -- and other doctored material will be used on the internet to sway the 2020 presidential election in November. Deepfakes have been made of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg boasting about controlling personal data and a foul-mouthed Barack Obama cursing misleading information. Last year, a video of Nancy Pelosi was altered to make the Democratic house speaker appear to be drunk during an interview. The video, which was altered without the aid of artificial intelligence, quickly went viral on social media.

The videos are part of a larger problem of dark patterns, Harris said. That term is used to describe how platforms can nudge users to watch more videos, read more content or even purchase specific items with fine-tuned algorithms that anticipate users' interests. While traditional marketing has long used techniques of subtle persuasion to get consumers to buy things, the internet surrounds us with these patterns in a powerful and inescapable way, he said.

Social media as a whole hasn't taken consistent positions on deepfakes and altered media. For example, YouTube removed the Pelosi video, while Twitter left it on its service. Facebook added fact-checker comments and curbed the video's spread on the social network.

On Monday, Facebook expanded its rules on deepfakes, barring users from posting them. The rules, however, don't ban all edited or manipulated videos. The Pelosi video would likely still be allowed on the site. Deepfake technology uses artificial intelligence to fabricate photorealistic copy images of real people using the interactions between points on a person's face.

The software powering deepfakes is becoming more sophisticated. In the past, hundreds of photos of a subject were needed to create a convincing deepfake. But last year, Samsung demonstrated technology that required just a single photo to produce a deepfake.

Deepfakes "exploit the shortcuts our brains rely on to discern what's authentic or trustworthy, and have now become completely and fundamentally indistinguishable from the real thing," Harris said in written remarks to the committee.

Donovan, an expert in technology and social change, warned lawmakers that "cheapfakes," or the use of simple editing tricks to distort videos, are just as dangerous as deepfakes. That applies to the Pelosi video, and lawmakers asked Bickert why Facebook didn't simply take the video down.

"Our approach is to give people more information, so that if something is going to be in the public discourse, they will know how to assess it," Bickert said. Facebook labeled the video as false, but Bickert said she now believes the company could have gotten the video to fact checkers faster.

There was limited discussion of new laws or regulatory actions that could curb the spread of misinformation. Hurwitz, the law professor, suggested that the US Federal Trade Commission could have untapped abilities to do to address misinformation that harms consumers. "If we already have an agency that has power, let's see what it's capable of," he said.

Lawmakers also acknowledged the risk of running afoul of the First Amendment by requiring social media companies to take down videos or other content.

"It can be messy business to on one hand call on them to take down things we don't like and still stay on the right side of the First Amendment," said Rep. Greg Walden, a Republican from Oregon who noted that he has a degree in journalism. On the other hand, he said, "If you go too far, we yell at you for taking things down that we like."

But some action needs to be taken, said Rep. Jan Schakowsky, a Democrat from Illinois who chairs the subcommittee that held the hearing. She said she considered the suggestion of another lawmaker that Facebook allow a third-party audit of its policies in advance of the 2020 presidential election to be a good first step. The next step could be regulation.

"The government of the United States of America does need to respond," Schakowsky said.

Originally published Jan. 8, 8:17 a.m. PT.

Updates, 9:47 a.m. and 10:46 a.m.: Adds more information from hearing testimony.