Coronavirus drug remdesivir shows 'clear-cut positive effect' in US trial

Experimental antiviral remdesivir holds promise as a treatment for COVID-19 -- but questions remain.

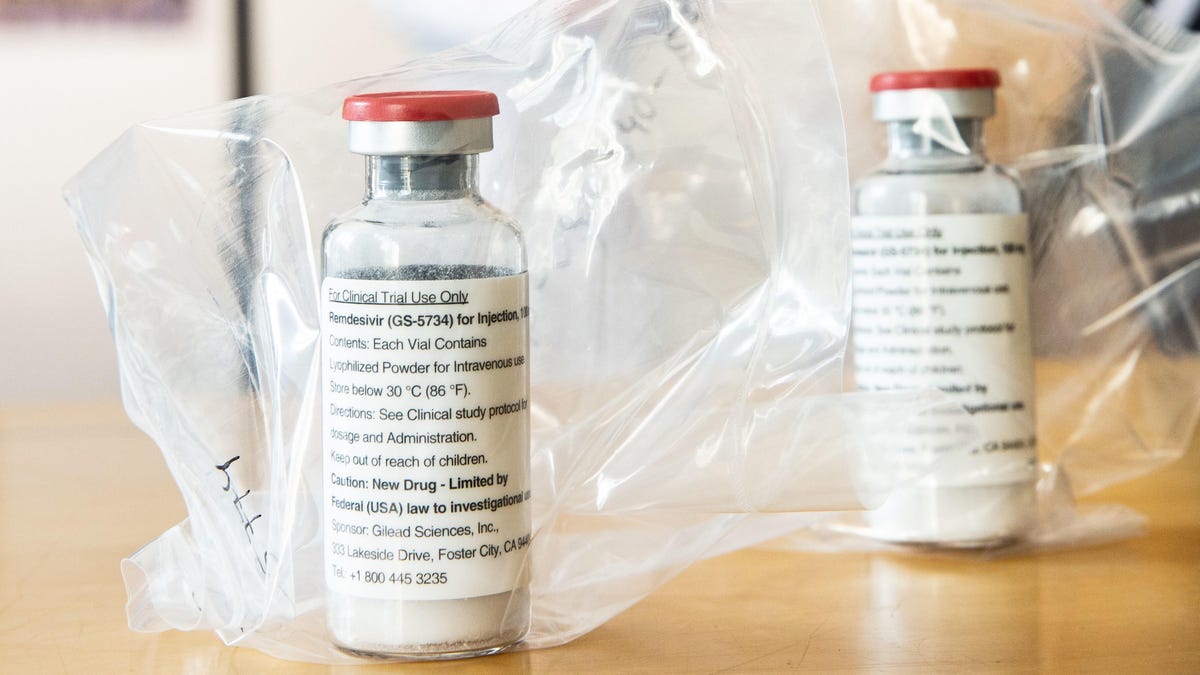

Gilead Sciences' experimental drug remdesivir has been floated as a coronavirus treatment since the earliest days of the pandemic.

Remdesivir, an experimental antiviral drug produced by biotech firm Gilead Sciences, has been one of the most talked about treatment options for COVID-19, even in the face of conflicting reports about its potential. On Wednesday, the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said preliminary data from a US-based clinical trial showed it can help patients recover from the coronavirus faster.

The preliminary findings were shared by Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the NIAID, during a press briefing at the White House on Wednesday. Fauci said the early results are "a very important proof-of-concept because what it has proven is that a drug can block this virus." However, the full peer-reviewed data from the trial are yet to be released but will be available in a forthcoming report, according to NIAID.

Remdesivir isn't specifically designed to destroy SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Instead, it knocks out a specific piece of machinery viruses use to replicate, known as "RNA polymerase." It was originally designed as a drug to treat Ebola, but when trialed, it turned out to be mostly unsuccessful. In 2017, a study published in the journal Science showed remdesivir to be effective against human coronaviruses in cells and mouse models.

The drug continued to show some benefit against coronaviruses in rhesus macaques and in smaller groups of patients with COVID-19, but larger studies in humans were called for.

The NIAID trial is the most comprehensive to date, enrolling more than 1,000 patients to test whether it will be a useful tool in patient care. There are two important takeaways from the preliminary findings. Patients who received remdesivir:

- had a 31% faster recovery time than patients who received the placebo

- had a slight, but statistically insignificant, improvement in survival -- the mortality rate was 8% compared with 11.6% for patients who received the placebo.

Remdesivir is likely to receive "emergency use" approval by The Food and Drug Administration, according to a report by the New York Times.

"The reason why we are making the announcement now is something that I believe people don't fully appreciate," Fauci said during the briefing Wednesday. "Whenever you have clear-cut evidence that a drug works, you have an ethical obligation to immediately let the people in the placebo group know so that they can have access."

During a randomized, controlled clinical trial, there are two groups of patients. One receives the experimental drug -- in this case, remdesivir -- while the other receives a placebo, a non-active drug. Which patients receive the drug and which receive the placebo is random, and patients aren't aware of what they're receiving. If a drug is found to be successful in helping patients improve, the health experts running the trial can decide to give all patients access to the beneficial drug.

Gilead, the biotech firm that produces remdesivir, is conducting its own clinical trial in patients with severe COVID-19. In response to the NIAID announcement, Gilead released preliminary data in a cohort of almost 400 patients. The study looked at how patients fared when receiving an infusion of remdesivir over periods of five days and 10 days. The longer treatment time didn't provide any added benefit, the company said.

"The study demonstrates the potential for some patients to be treated with a 5-day regimen," Merdad Parsey, chief medical officer at Gilead Sciences, said in a press release. Parsey suggests this could "significantly expand the number of patients who could be treated with our current supply of remdesivir."

Gilead's preliminary data also suggests treating patients early (within 10 days of symptom onset) may help them recover faster. However, Gilead's trial doesn't contain a placebo group of patients, making it difficult to draw conclusions.

On the same day as NIAID's announcement, results from a placebo-controlled clinical trial of 237 patients in Hubei, China, was published in medical journal The Lancet. The peer-reviewed report compared 158 patients receiving remdesivir with 79 patients on placebo. The trial was terminated early because the outbreak in China came to a grinding halt.

In its small group of patients, the team found remdesivir had no statistically significant clinical benefit. However, in patients treated with remdesivir within 10 days of symptom onset, remdesivir was associated with a reduction in recovery time. However, the research team notes it couldn't adequately assess whether remdesivir provides clinical benefits to COVID-19 patients because of the study's early termination.

Mike Ryan, head of the WHO's emergencies programme, declined to comment on the reports during a press briefing Wednesday, according to Reuters. "I wouldn't like to make any specific comment on that, because I haven't read those publications in detail," he said.

Where does this leave Gilead's experimental drug? There's still work to be done. Picking through the data from the NIAID study will help paint a better picture of remdesivir's potential as a coronavirus treatment option. Though the drug shows promise, it doesn't appear to significantly improve the mortality rate and the data on clinical benefits remain ambiguous.