Brain scans could uncover dyslexia before kids learn to read

A type of MRI scan reveals the size and set-up of a part of the brain that appears to be smaller in children with dyslexia.

Dyslexia is a common learning disorder that affects around 1 in 10 people in the U.S., where it is typically diagnosed around second grade but sometimes goes undiagnosed and unmanaged well into adulthood. And though it is technically a learning disorder, it actually occurs in people with normal vision and intelligence, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Now researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston Children's Hospital say that a type of MRI scan called diffusion-weighted imaging could help diagnose the disorder in kids before they even start to learn to read -- a discovery that could help teachers and experts intervene early to manage it.

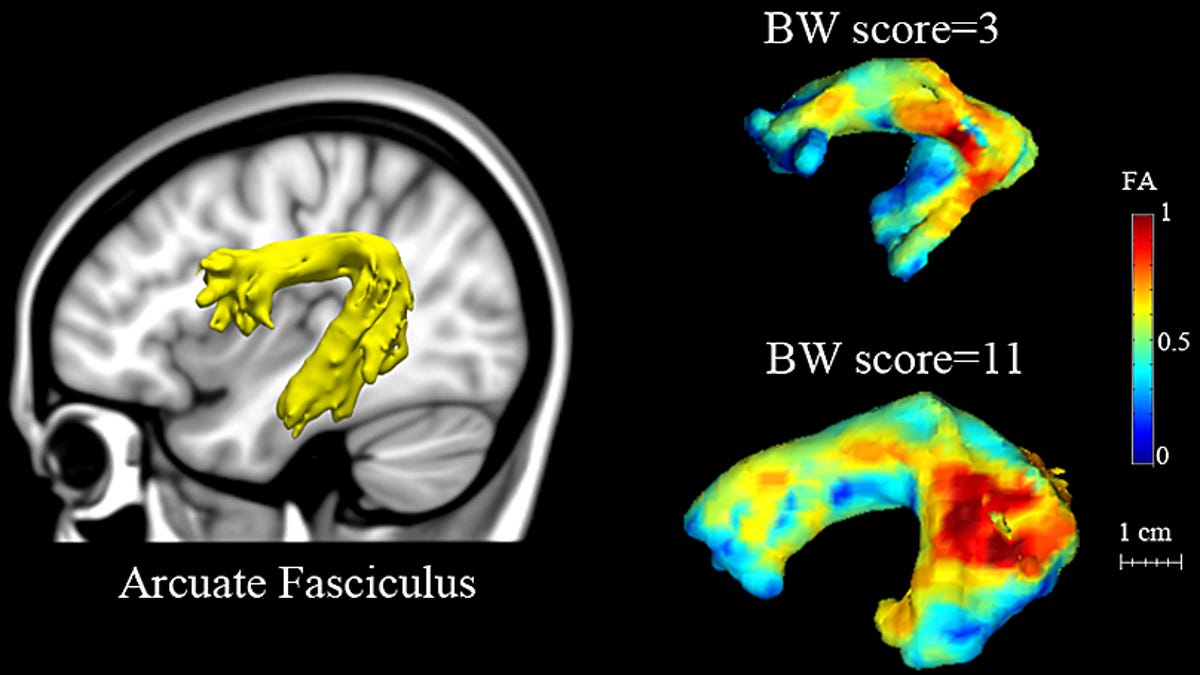

The research, published August 14 in the Journal of Neuroscience, involved scanning the brains of 40 children who are part of a larger study assessing pre-reading skills. Researchers confirmed a correlation between the size and organization of the arcuate fasciculus and performance on tests of what is called phonological awareness, or the ability to identify and manipulate the sounds of language.

Previous work has already demonstrated that this structure is smaller and less organized in adults with poor reading skills than those who read normally. Until now, it was unclear whether that difference actually caused the reading difficulties or simply resulted from lack of experience in those who don't read as much due to their poorer reading skills.

"We were very interested in looking at children prior to reading instruction and whether you would see these kinds of differences," John Gabrieli, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences and a member of MIT's McGovern Institute for Brain Research, said in a school news release. "At the moment when the children arrive at kindergarten, which is approximately when we scan them, we don't know what factors lead to these brain differences."

Finding an early, pre-reading biomarker for dyslexia could mean avoiding some of the psychological distress that some kids suffer when they encounter reading difficulties. Gabrieli says he hopes that we can accurately predict who will become dyslexic early using a simple test instead of just waiting for kids to struggle.