At Super Bowl, detecting threats is like finding a needle in a haystack

Haystax's cloud-based tools are helping New York and New Jersey security officials navigate massive amounts of data in order to find any possible threat. Just a few years ago, this would have been impossible.

Imagine this scenario: In the course of an hour this week, four different people involved in Super Bowl setup require emergency medical assistance, all for nausea, and all in separate incidents.

It could be that some vendor is serving spoiled food, or it could be a complete coincidence. But it could also be a sign of some sort of criminal or terrorist act aimed at America's biggest sporting event. For the people in charge of public safety at and around MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J., home to this Sunday's NFL championship between the Denver Broncos and the Seattle Seahawks, uncovering the cause of four similar ambulance calls, if they were to take place in such short order, would be an extremely urgent matter.

Just a few years ago, it would have been next to impossible for security personnel to make the connection between four EMS calls like that in real time. There was no technology available then that could bring the separate events to their attention and help them easily track what was happening in each case, or how, or if, they were connected.

But in January 2012, as Indianapolis prepared to host Super Bowl XLVI, that precise scenario played out one afternoon in the Super Bowl Village there, recalled Gary Coons, the incident commander for that year's big game.

As Indianapolis' homeland security chief, Coons was the top dog of a massive security apparatus working to protect the Super Bowl and the tens of thousands of people in town for the game, and the week's worth of partying preceding it. Everywhere he went that week, he could monitor the event's critical infrastructure, as a wide variety of local threat sensors, 911 call systems, and even game-oriented social media fed information into a software package that Coons and many other security personnel could monitor in real-time via smart phones or iPads.

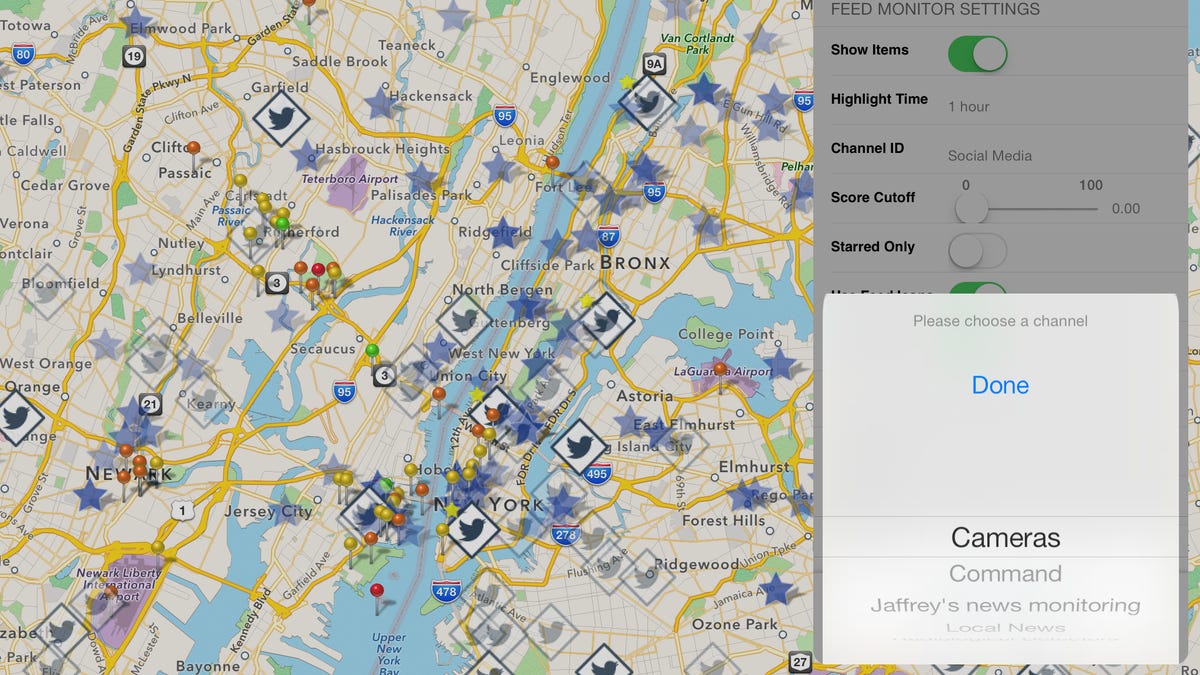

That system, known now as the Haystax Public Information Cloud, is designed to pull in huge flow of raw data -- things like camera feeds, radiological monitors, RFID and GPS systems, and social media -- and algorithmically bring the most important data points to the top. In other words, it's designed to find the needle in the haystack.

This week, Super Bowl XLVIII is being held in the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, presenting security officials with a far greater logistical challenge than anything Coons had to manage. Haystax's latest technology will be at the center of it all, providing everyone from the incident commander in charge of securing the event on down to hundreds of other essential security personnel with the ability to see what's happening on the ground, as it happens, and to quickly assess just about any kind of threat, real or perceived, that might arise. Ideally before it becomes the kind of serious problem where lives or property are at risk.

Back in Indianapolis, Coons recalled that the Haystax system made it possible to recognize the common thread between the four emergency calls in short order and take action as fast as possible. He sent a joint hazardous team to the scene that included fire hazmat specialists, support teams, and a biological hazardous materials specialist, all on the chance that something serious was happening. Fortunately, the four nausea cases turned out to be unrelated, Coons told CNET, but without the technology, "we would never have been able to pick up on having those four incidents at the same time in the same location."

Level 1 national security event

Every Super Bowl since 9/11 has been designated a Level 1 national security event. And with this year's big game being the first-ever in the New York-New Jersey region, you can imagine how seriously officials are taking security. "Our tactical teams have been training throughout the year for different scenarios," Aaron Ford, the FBI agent in charge of Super Bowl security told ESPN.com, "to include active shooter, bomb threats, and casualties related to chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threats."

All that monitoring will generate a massive amount of raw data, and that's where Haystax's technology comes into play. According to ESPN.com, there will be 3,000 NFL security pros on hand for the Super Bowl, along with 700 New Jersey State Police troopers, and many others. Without a way to deliver meaningful information to those people, detecting threats would be meaningless. But with Haystax's tools, including the mobile Digital Sandbox, and the Constellation desktop dashboard, the data can be easily distilled.

According to Anthony Beverina, president of public safety and commercial business for Haystax, there will likely be 40 different public agencies, plus all the NFL and other commercial entities, working to make sure everything goes well during Super Bowl week. Haystax technology, Beverina said, provides "a cloud-based environment where all can see the most important things around them, and collaborate on solving big problems."

Haystax's technology is built around patented risk management algorithms "that allow us to fuse a lot of information -- hundreds and hundreds of feeds -- and assemble them to find important risk elements."

The goal of the system is to algorithmically surface the most important data points and deliver them to the right decision makers. Much of that data is coming from automatic systems. But more is coming from personnel deployed at points around the area sending back reports from their mobile devices via Haystax's so-called Digital Sandbox tool of anything from someone taking pictures of security infrastructure to cases of trespassing, unexpected protests or flash mobs, and more. "We will process all that through our engine," Beverina said, "and we will find through our algorithms now that's important based on what we know. We present that to an analyst and that analyst says, 'I think there's a potential problem here.'"

In an environment like the New York-New Jersey area, with millions of people within a short distance of MetLife Stadium, the amount of potential input is mind-boggling, especially when you throw possible bad weather into the mix. Not to mention the fact that potential terrorists could be physically entering the system from any number of far-flung transportation hubs, or trying to surreptitiously coordinate something nefarious through social media. The authorities can't afford to get bogged down by low-priority problems, yet might be dealing with simultaneous issues such as a fire, a suspicious person, and a suspicious package.

Haystax is designed to make all of that manageable.

5th time around

This year's Super Bowl marks the fifth time the technology behind Haystax's technology has been used to help secure the NFL's championship game. But things are quite different this time around. For one thing, social media was in its infancy the first time around, and the total data flow from mobile devices this year dwarfs that of previous Super Bowls.

At the same time, each city presents a different challenge. In Indianapolis two years ago, the Super Bowl was jammed into a very small downtown area that, by and large, was easy to monitor. In New Orleans last year, the game was in some ways drowned out by the always-on party atmosphere in the French Quarter, Beverina recalled.

This time around, however, the job of monitoring all potential threats is monumentally larger, especially given that tens of thousands of people will be heading to the game via public transportation that originates miles from the stadium. There will also be countless people driving across bridges and taking express buses, and all of those people will be passing through monitored choke points - all generating more data that must be interpreted.

"You [can] screen at the bus terminal and at the transit stops as far out as you want," Beverina said, but all of that will be generating more and more data, and complicating what must be analyzed. Still, that's Haystax's job. If the technology works as planned, and as it has in the past, then the public will be safe, and the focus can be on football. "It's about speed of action. How fast can you get people with knowledge of the action on the scene...It's about managing chaos."