Aereo case is a struggle for TV broadcasters

Judge concludes preliminary injunction hearing that was hard fought by broadcasters and video service. But will court shut Aereo down?

NEW YORK--Wave goodbye to watching the Super Bowl for free if Aereo is allowed to operate, lawyers for the nation's largest broadcasters told a federal court yesterday.

Aereo's attorneys scoffed at that notion. They said that Aereo's Internet video service will only make it easier for users to access freely available over-the-air broadcasts, which they have every right to do. The two sides generated plenty of drama in a Manhattan federal district court as two days of arguments were wrapped up. The judge now must decide whether to shut down Aereo.

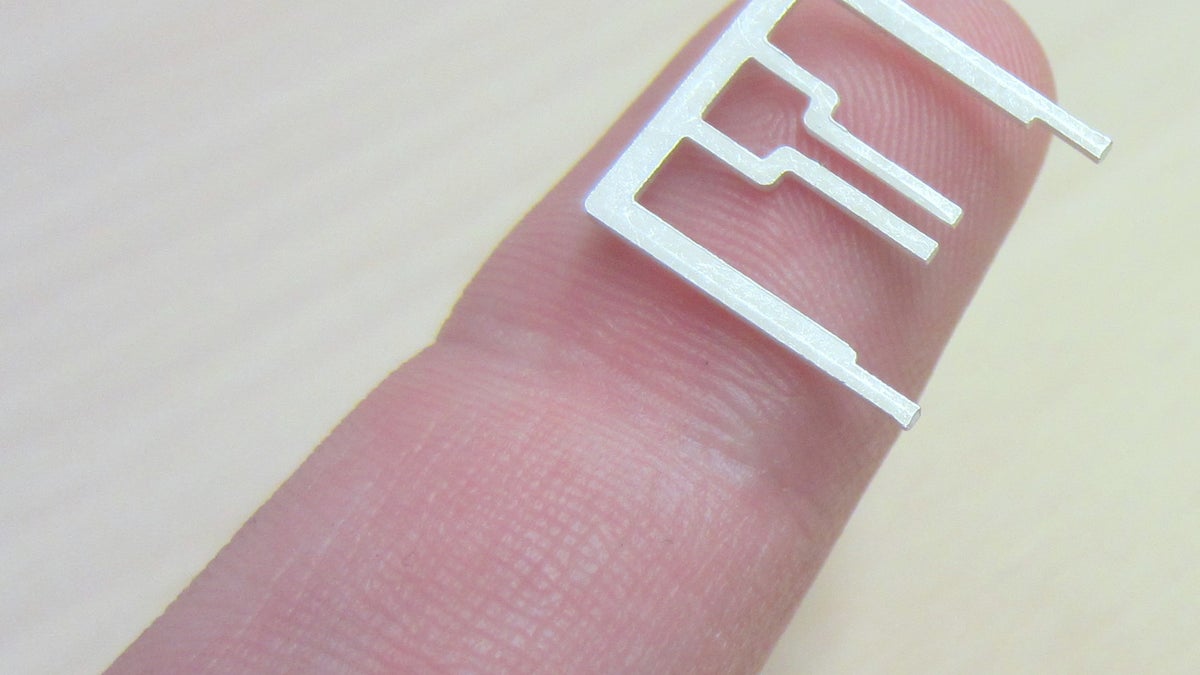

The parties were in court as a result of copyright lawsuits filed in March against Aereo by two different groups of New York broadcasters. They include ABC, NBC, Fox and CBS (the parent company of CNET). Aereo is the Barry Diller-backed online service that launched in March and is for the time being available exclusively in New York. Aereo provides live, over-the-air TV for a monthly fee of $12. The service connects viewers via the Internet to their own dime-sized TV antennas stored at the company's facility. Subscribers also use the Web to control the antennas as well as a digital video recorder.

The stakes are high so there was plenty of tension. The broadcasters claim that Aereo retransmits their programming without permission or compensating them and have asked U.S. District Court Judge Alison Nathan to order Aereo to cease distribution immediately. Aereo executives told the judge that they don't transmit anything but it is instead their subscribers who are doing it. Aereo's lawyers told the judge that if she grants a preliminary injunction against the service, the company would be dead in seven months.

The hearings had everything you could ask for in a tech vs. old media copyright case. Some of the best copyright lawyers in the country battled it out over two days. Some among them were accused of badgering witnesses or getting into so-called verbal "wrestling matches" with the judge. What became apparent as they argued the issues is how much the law is being reshaped by technology.

"So, technology has beaten the public performance restriction?" Nathan asked Aereo's lawyers during closing arguments, which seemed to stun attorneys on both sides. She was noting that the way the law reads, it appears that all one has to do to satisfy the part of copyright law that requires creators be paid when their work is distributed publicly is to distribute a unique copy for every individual subscriber and call it a private performance.

Aereo's lawyers pointed out there were still plenty of teeth in the public-performance requirements. Nathan's comments, however, illustrated one important fact: copyright law has not managed to keep pace with technological advancements and as a result the broadcasters -- and indeed most media sectors -- are more vulnerable than ever to these types of challenges.

This was illustrated again when Nathan refused to accept some of the arguments made by Steven Fabrizio, one of the broadcasters' attorneys, about how Cartoon Network v. CSC Holdings, commonly known as the Cablevision decision, affected Aereo. Nathan interrupted and peppered Fabrizio, a former attorney for the Recording Industry Association of America, with questions and comments during his closing arguments.

Cablevision, a cable company, sought to create and host its own TiVo like digital video recorder. Many of the same companies involved in suing Aereo tried to stop Cablevision. In 2008, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that the automated copying of content at the user's request was not direct copyright infringement. The Appeals court also found that replaying movies or music to an original audience (after a live performance) was not necessarily a public performance, and, finally, that buffering was not unlawful copying.

"Doesn't Cablevision bind me here?" Nathan asked.

When Fabrizio told her that Cablevision didn't apply in the Aereo case, Nathan seemed dissatisfied.

"At some point you have to tell me how [the Cablevision] analysis should affect my decision."

Soon after, the judge called for a short break. It was then that Fabrizio's voice was picked up over a microphone and he could be heard saying he was unable to get out of the "wrestling match" with Nathan about Cablevision. When it was time for Aereo's attorneys to give their closing arguments, they pounced on Fabrizio's troubles.

They told the judge that if the broadcasters didn't have answers about Cablevision, they certainly did and they listed numerous ways that Aereo was similar to Cablevision's DVR.

Later, Bruce Keller, another lawyer representing the broadcasters, tried to tackle the issue of why Cablevision should not protect Aereo. He told the judge that because Aereo users weren't getting a complete and uninterrupted copy of a broadcast, but were instead watching in real time, it was therefore a public performance. He also noted that in Cablevision, users were making copies with their DVRs from authorized broadcast streams. In contrast, Aereo had no authorization to broadcast, Keller said. He told her that Cablevision didn't give her "all the tools she needed" to decide Aereo and she would have to grapple with some of issues herself.

Keller was at his most persuasive when it came time to discuss whether Aereo posed irreparable harm to the broadcasters. The judge must be convinced such harm would occur before she can grant a preliminary injunction.

He said that Americans are entitled to free over-the-air television. He said that Aereo's live broadcasts were just a means to lure viewers into the $12 a month subscription plan so the company could eventually sell movies to subscribers. He said if Aereo wins, free TV will disappear and the era of the pay-for-view broadcast model would begin.

"This will happen as surely as night follows day," Keller told the court.

He predicted that if Aereo is permitted to operate, the cable companies will see no more reason to pay for retransmission fees, part of the broadcasters' "lifeblood." As for Internet distribution, Keller told the court that the broadcasters should be allowed to explore these new markets with their content.