A transit of Mercury was first seen in 1631 and nearly disregarded

The first time the planet was spotted sauntering in front of the sun, it seemed like a mistake. The double take fundamentally reordered our view of the cosmos.

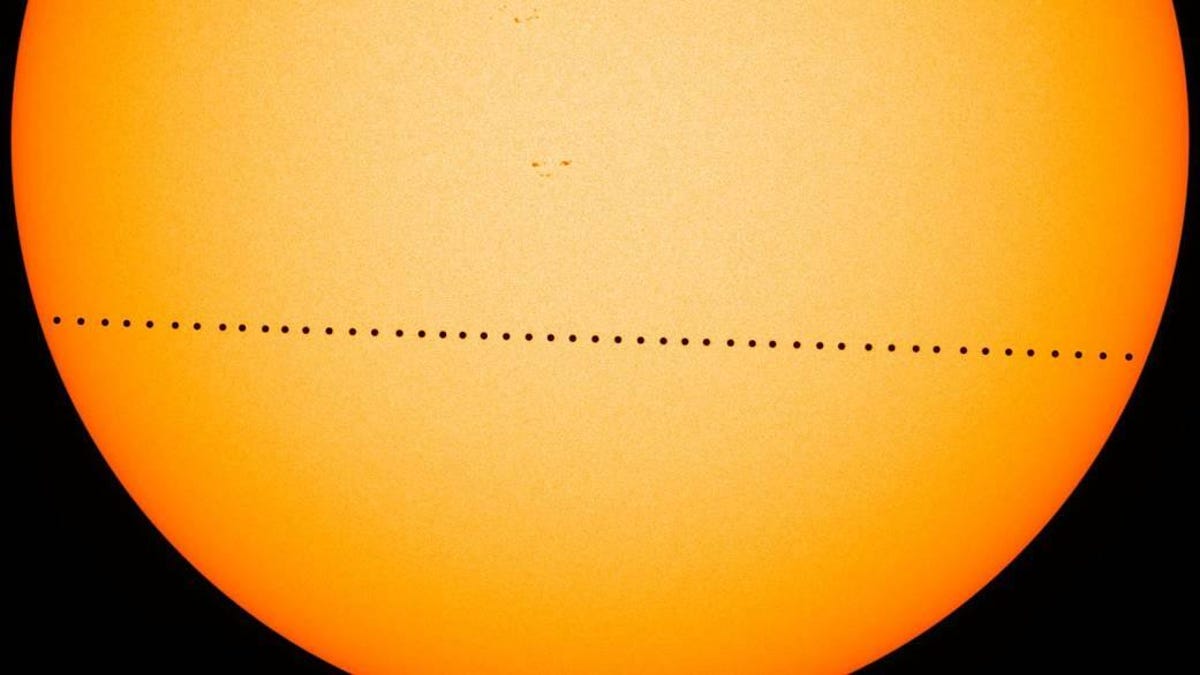

A composite image of Mercury's journey across the sun in 2016.

The transit of Mercury in front of the sun will happen Monday, a rare event that won't be seen again until 2032. Astronomers have been observing the celestial traverse for nearly four centuries now, but the first reliable observation, in 1631, was so different than what scientists of the time expected it was almost thrown out.

Observations of the transit of Mercury have been reported as far back as the ninth century, but after Galileo introduced the telescope in 1610, it became clear that earlier observers were probably seeing sunspots rather than Mercury.

For the transit of Nov. 7, 1631, a number of astronomers set up to capture Mercury's movement in front of our star. Only one, a catholic priest in Paris named Pierre Gassendi, published his observations, which indicate he couldn't quite believe what he was seeing at the time.

"I was far from suspecting that Mercury would project such a small shadow," Gassendi wrote.

The priest presumed the small spot he saw was just a sunspot because he was expecting the disk of Mercury to cover about one-tenth of the sun, when in reality it appears more like one-hundredth the size of our star.

"It is indeed curious that early observers thought they were looking at Mercury on the sun when they saw a sunspot and that now Gassendi, when he was, in fact, observing Mercury on the sun, thought he was looking at a sunspot," Albert Van Helden wrote in 1976 for the Journal for the History of Astronomy.

Back in Gassendi's time, there was still quite a lot of disagreement about the arrangement and scale of the cosmos. This was the time period when scientists were fighting over whether the Earth revolves around the sun or vice versa. Interestingly, though, both camps more or less agreed on the approximate sizes of the planets. And when it came to Mercury, they were both wrong.

"Thankfully, he continued to observe for several hours and noticed that the tiny dark spot moved much faster across the face of the sun and along a different path than a sunspot would," writes Todd Timberlake, author of Finding Our Place in the Solar System.

That persistence would pay off in the long run and lead to some key corrections in our understanding of Mercury's orbit and the size of the planets. Mercury's unexpected small size would also eventually lead to a more accurate measurement of the distance between the Earth and sun. This would, in turn, give us a better idea of just how vast the universe is.

All this understanding was almost delayed, though, when Mercury was momentarily written off as just another spot on the sun.

Originally published Nov. 8.