A smarter mirror for cheaper solar power

Using digital technologies, startup Thermata looks to slash the cost of concentrating solar power plants which is needed to stave off the onslaught from cheaper solar photovoltaic panels.

Rather than try to reinvent the solar cell, startup Thermata has engineered a high-tech mirror to cut the cost of solar power.

The company, incubated at Idealabs, has completed initial testing on a system executives say can cut the cost of sun-tracking mirrors, or heliostats, in half using cameras and other digital technologies. Thermata plans to start beta testing the heliostats this year with potential customers, which are concentrating solar power technology companies, and with Sandia National Laboratories.

Thermata typifies a new breed of green-technology startup which is targeting a specific niche in energy using technologies from other fields. Its system uses a camera to detect the angle of heliostats and a mesh network of microprocessors to position each mirror with the ideal tilt. In a concentrating solar power plant, thousands or even millions of heliostats concentrate light onto a tower to produce steam, which turns a turbine to generate electricity.

"Instead of using calculations and past knowledge to infer where the mirror is, we can physically measure the angle and control it explicitly," said CEO Terry Bailey. "We've use intelligence instead of steel."

Heliostats now used at concentrating solar power plants are heavy-duty pieces of equipment, mounted on pylons to withstand high winds and connected via wires to control their motion.

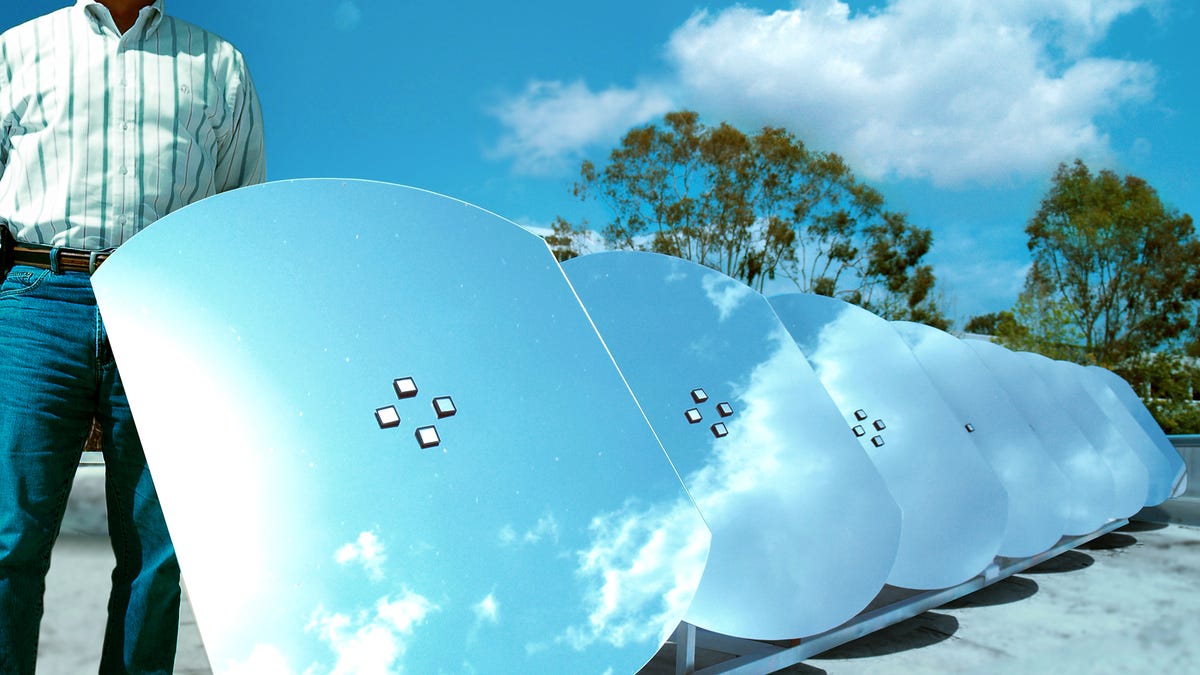

Thermata's system is designed to be smaller, lighter, and operate wirelessly. There are eight heliostats on a "pod" with the mirrors' motors operated by small, two-watt photovoltaic solar panels, explained Chief Technology Officer Brad Hines.

Each mirror is equipped with four small "diffusers," or small square mirrors raised above the surface of the heliostat. A camera placed at a distance and out of the glare made by the heliostat takes pictures of the diffusers. Based on the light pattern and intensity, it can determine its location and optimize the tilt, Hines said.

Each heliostat has a microprocessor with a Zigbee wireless chip in it. Those nodes create a mesh network to send information to a central computer which dispatches information on the best position.

"The fact that we can talk to these heliostats wirelessly is a big part of the technology and that technology has only really become available in the last three or four year," Hines said. "That, combined with the optical processing, is what enabled our invention."

Small is beautiful

Having a smaller heliostat means lower costs, which is significant since heliostats are about 40 percent of the cost in solar power plant.

The size means mirrors can be closer to the ground and require less-expensive mounting, Hines said. Gears can be made out of plastic, rather than steel, and the heliostats can be handled by two people, making installation simpler. "We've taken what was traditionally aerospace engineering and we've turned it into automotive," Hines said.

As for the camera and optics, Hines said that digital imaging has progressed so much, the company can get ample imaging processing for under $25 or $30 and built-in image stabilization means cameras can operate on poles which move in the wind.

It's still not clear that Thermata's system will satisfy concentrating solar power developers' demands, but those companies, such as BrightSource Energy and SolarReserve, do need to lower their costs.

The dramatic drop in the cost of solar panels has forced some plant developers to drop solar thermal systems in favor of solar photovoltaics. Thermata's heliostats can also be used for enhanced oil recovery, where steam is injected in used oil wells to stimulate more flow.

Thermata estimates its smaller, cheaper heliostats can take roughly $100 million off of a $600 million solar power plant construction cost, based on savings on heliostats, wiring, and labor. The key is making smaller, lighter devices, something which solar engineers have long desired but has been difficult to do.

"As you go bigger, you get taller and then the wind becomes a significant factor to the design. Then you need yet more precision, more weight, and stiffness -- it's an escalating problem," said Bailey. "This breakthrough allows us to go small and low."