Little-known meteor shower this month could have dangerous stowaways

The Beta Taurids are rarely seen, but there's increasing evidence they've been strongly felt at least once in the past.

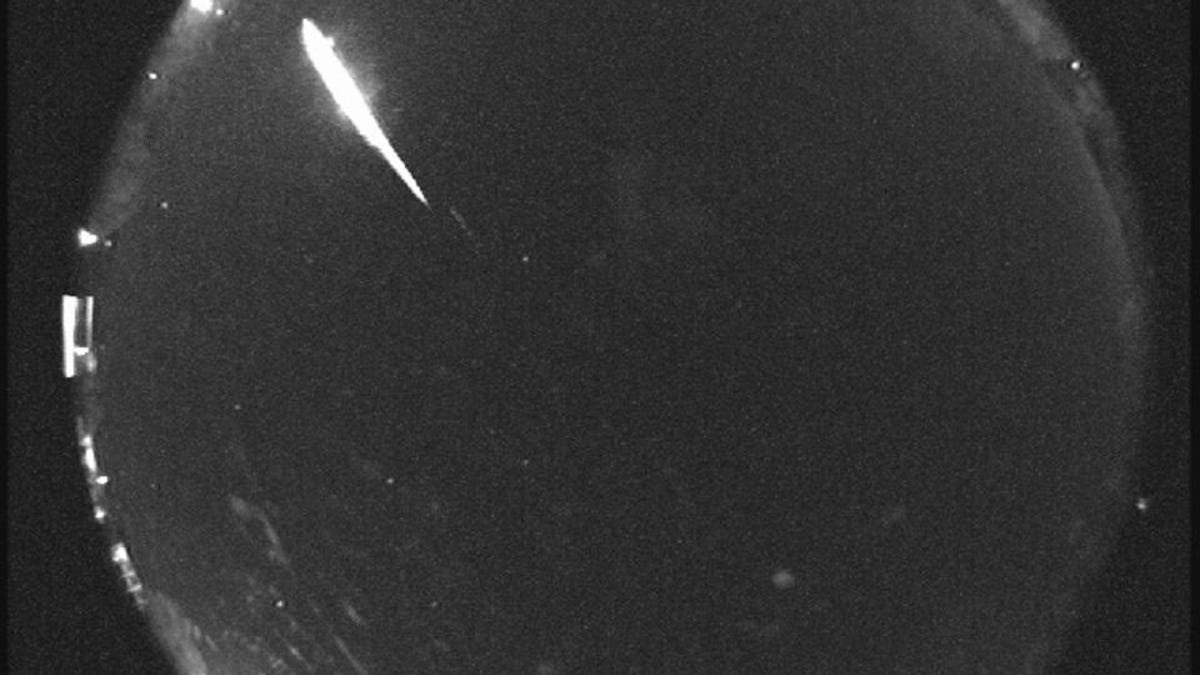

A Taurid fireball captured by NASA's sky cameras in 2015.

August's Perseid meteor shower is known for being among the year's most dazzling, but a lesser-known shower in June could be the most dangerous.

The Beta Taurid meteor shower is less well known because it is considered a weak daytime shower that peaks after sunrise, making it very difficult to spot from Earth. But for at least a few decades now, some scientists have suspected that the Beta Taurids have made their presence felt in other ways in the past.

Oxford scientists published research in 1993 suggesting that the space rock behind the Tunguska Event may've been hiding among the cloud of debris left behind by Comet Encke, which is responsible for the Taurids. The little bits of dust and pebbles burn up in our atmosphere and are seen as "shooting stars." But the researchers said there's reason to believe that Encke's dust cloud also harbors bigger boulders, and that it dropped one on the Tunguska River region of Siberia in 1908.

The Tunguska Event represents perhaps the most powerful meteoroid impact with the Earth in modern times. A bolide exploded in the atmosphere over the Siberian wilderness, flattening the forest and tossing people from their chairs over 40 miles away.

More recent research has backed up the idea that the Tunguska bolide may've come from a so-called "swarm," or dense pocket of debris, within the much broader cloud of Taurid junk. It also says we could be passing relatively near that swarm of debris very soon.

"If the Tunguska object was a member of a Beta Taurid stream, then the last week in June 2019 will be the next occasion with a high probability for Tunguska-like collisions or near-misses," reads a paper by researchers from the Universities of New Mexico and Western Ontario presented at an American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in December.

Related research finds that this month Earth will make its closest approach to the center of the Taurid swarm since 1975. The scientists aren't suggesting that we should worry about a Tunguska-like impact, as we'll still be 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) away from the swarm center.

However, there could be a "possibility of enhanced daylight fireballs and significant airbursts," later this month, according to the AGU paper.

Astronomers are hoping to take advantage of the close approach to get a better look inside the swarm to see if they can spot any large objects.

Cataloging any hidden asteroids within the Taurids now could be especially useful in the 2030s, when Earth will make an even closer pass by the swarm -- the closest in over a century -- not once, but twice.